Interpreting Perfect Competition Graphs

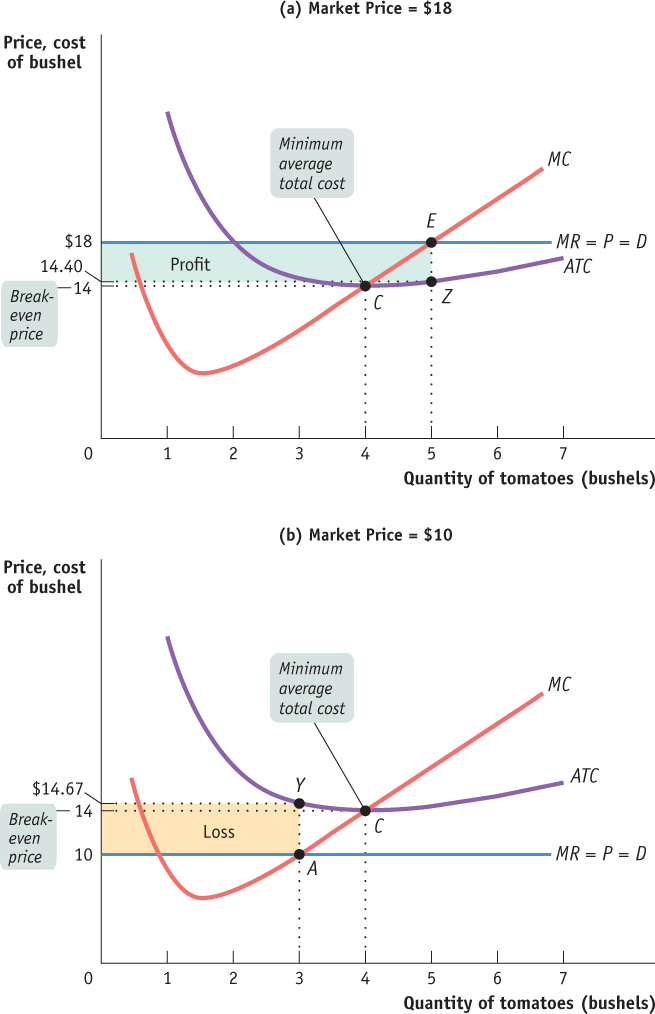

Figure 59.1 illustrates how the market price determines whether a firm is profitable. It also shows how profit is depicted graphically. Each panel shows the marginal cost curve, MC, and the short-

| Figure 59.1 | Profitability and the Market Price |

In panel (a), we see that at a price of $18 per bushel the profit-

Jennifer and Jason’s total profit when the market price is $18 is represented by the area of the shaded rectangle in panel (a). To see why, notice that total profit can be expressed in terms of profit per unit:

AP® Exam Tip

Memorize the formula for profit because you won’t be given a formula sheet for the AP® exam.

(59-

or, equivalently, because P is equal to TR/Q and ATC is equal to TC/Q,

Profit = (P – ATC) × Q

The height of the shaded rectangle in panel (a) corresponds to the vertical distance between points E and Z. It is equal to P - ATC = $18.00 - $14.40 = $3.60 per bushel. The shaded rectangle has a width equal to the output: Q = 5 bushels. So the area of that rectangle is equal to Jennifer and Jason’s profit: 5 bushels × $3.60 profit per bushel = $18.

AP® Exam Tip

AP® exam questions may give you a scenario about profit, cost, or revenue at a specific output. Drawing the firm’s graph may help you visualize the answer more easily.

What about the situation illustrated in panel (b)? Here the market price of tomatoes is $10 per bushel. Producing until price equals marginal cost leads to a profit-

How much do they lose by producing when the market price is $10? On each bushel they lose ATC - P = $14.67 - $10.00 = $4.67, an amount corresponding to the vertical distance between points A and Y. And they produce 3 bushels, which corresponds to the width of the shaded rectangle. So the total value of the losses is $4.67 × 3 = $14.00 (adjusted for rounding error), an amount that corresponds to the area of the shaded rectangle in panel (b).

But how does a producer know, in general, whether or not its business will be profitable? It turns out that the crucial test lies in a comparison of the market price to the firm’s minimum average total cost. On Jennifer and Jason’s farm, average total cost reaches its minimum, $14, at an output of 4 bushels, indicated by point C. Whenever the market price exceeds the minimum average total cost, there are output levels for which the average total cost is less than the market price. In other words, the producer can find a level of output at which the firm makes a profit. So Jennifer and Jason’s farm will be profitable whenever the market price exceeds $14. And they will achieve the highest possible profit by producing the quantity at which marginal cost equals price.

Conversely, if the market price is less than the minimum average total cost, there is no output level at which price exceeds average total cost. As a result, the firm will be unprofitable at any quantity of output. As we saw, at a price of $10—

The break-

The minimum average total cost of a price-

So the rule for determining whether a firm is profitable depends on a comparison of the market price of the good to the firm’s break-

Whenever the market price exceeds the minimum average total cost, the producer is profitable.

Whenever the market price equals the minimum average total cost, the producer breaks even.

Whenever the market price is less than the minimum average total cost, the producer is unprofitable.

The Short-Run Production Decision

You might be tempted to say that if a firm is unprofitable because the market price is below its minimum average total cost, it shouldn’t produce any output. In the short run, however, this conclusion isn’t right. In the short run, sometimes the firm should produce even if price falls below minimum average total cost. The reason is that total cost includes fixed cost—cost that does not depend on the amount of output produced and can be altered only in the long run. In the short run, fixed cost must still be paid, regardless of whether or not a firm produces. For example, if Jennifer and Jason have rented a tractor for the year, they have to pay the rent on the tractor regardless of whether they produce any tomatoes. Since it cannot be changed in the short run, their fixed cost is irrelevant to their decision about whether to produce or shut down in the short run. Although fixed cost should play no role in the decision about whether to produce in the short run, another type of cost—

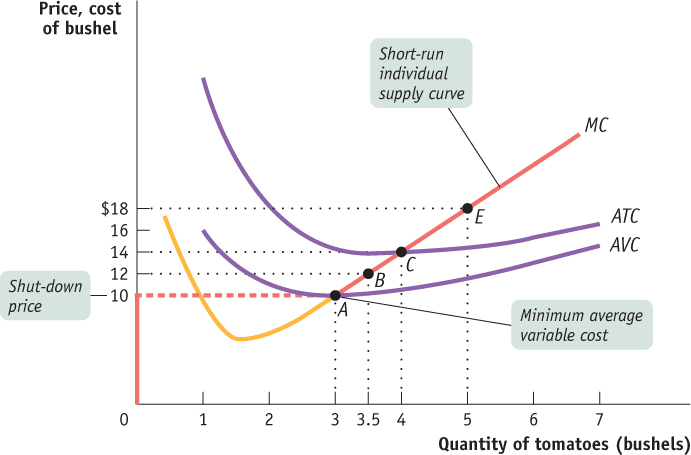

Let’s turn to Figure 59.2: it shows both the short-

| Figure 59.2 | The Short- |

The Shut-Down Price

We are now prepared to analyze the optimal production decision in the short run. We have two cases to consider:

When the market price is below the minimum average variable cost

When the market price is greater than or equal to the minimum average variable cost

A firm will cease production in the short run if the market price falls below the shut-

When the market price is below the minimum average variable cost, the price the firm receives per unit is not covering its variable cost per unit. A firm in this situation should cease production immediately. Why? Because there is no level of output at which the firm’s total revenue covers its variable cost—

When price is greater than minimum average variable cost, however, the firm should produce in the short run. In this case, the firm maximizes profit—

But what if the market price lies between the shut-

This means that whenever price falls between minimum average total cost and minimum average variable cost, the firm is better off producing some output in the short run. The reason is that by producing, it can cover its variable cost and at least some of its fixed cost, even though it is incurring a loss. In this case, the firm maximizes profit—

It’s worth noting that the decision to produce when the firm is covering its variable cost but not all of its fixed cost is similar to the decision to ignore a sunk cost, a concept we studied previously. You may recall that a sunk cost is a cost that has already been incurred and cannot be recouped; and because it cannot be changed, it should have no effect on any current decision. In the short-

And what happens if the market price is exactly equal to the shut-

The short-

Putting everything together, we can now draw the short-

Do firms sometimes shut down temporarily without going out of business? Yes. In fact, in some industries temporary shut-

Changing Fixed Cost

Although fixed cost cannot be altered in the short run, in the long run firms can acquire or get rid of machines, buildings, and so on. In the long run the level of fixed cost is a matter of choice, and a firm will choose the level of fixed cost that minimizes the average total cost for its desired output level. Now we will focus on an even bigger question facing a firm when choosing its fixed cost: whether to incur any fixed cost at all by continuing to operate.

In the long run, a firm can always eliminate fixed cost by selling off its plant and equipment. If it does so, of course, it can’t produce any output—

Consider Jennifer and Jason’s farm once again. In order to simplify our analysis, we will sidestep the issue of choosing among several possible levels of fixed cost. Instead, we will assume that if they operate at all, Jennifer and Jason have only one possible choice of fixed cost: $14. Alternatively, they can choose a fixed cost of zero if they exit the industry. It is changes in fixed cost that cause short-

Suppose that the market price of organic tomatoes is consistently less than the break-

Conversely, suppose that the price of organic tomatoes is consistently above the break-

As we will see shortly, exit and entry lead to an important distinction between the short-

Summing Up: The Perfectly Competitive Firm’s Profitability and Production Conditions

In this module we’ve studied what’s behind the supply curve for a perfectly competitive, price-

Table 59.1Summary of the Perfectly Competitive Firm’s Profitability and Production Conditions

| Profitability condition (minimum ATC = break- |

Result |

| P > minimum ATC | Firm profitable. Entry into industry in the long run. |

| P = minimum ATC | Firm breaks even. No entry into or exit from industry in the long run. |

| P < minimum ATC | Firm unprofitable. Exit from industry in the long run. |

| Production condition (minimum AVC = shut- |

Result |

| P > minimum AVC | Firm produces in the short run. If P < minimum ATC, firm covers variable cost and some but not all of fixed cost. If P > minimum ATC, firm covers all variable cost and fixed cost. |

| P = minimum AVC | Firm indifferent between producing in the short run or not. Just covers variable cost. |

| P < minimum AVC | Firm shuts down in the short run. Does not cover variable cost. |

Prices Are Up . . . but So Are Costs

Prices Are Up . . . but So Are Costs

In 2005 Congress passed the Energy Policy Act, mandating that by the year 2012, 7.5 billion gallons of alternative fuel—

This development caught the eye of American farmers like Ronnie Gerik of Aquilla, Texas, who, in response to surging corn prices, reduced the size of his cotton crop and increased his corn acreage by 40%. He was not alone; within a year, the amount of U.S. acreage planted in corn increased by 15%.

Although this sounds like a sure way to make a profit, Gerik was actually taking a big gamble: even though the price of corn increased, so did the cost of the raw materials needed to grow it—

Despite all of this, what Gerik did made complete economic sense. By planting more corn, he was moving up his individual short-

So the moral of this story is that farmers will increase their corn acreage until the marginal cost of producing corn is approximately equal to the market price of corn—