Tacit Collusion

Clearly, the players in any prisoners’ dilemma would be better off if they had some way of enforcing cooperative behavior. In terms of the examples from the previous module, criminals Richard and Justin would benefit from successfully swearing to a code of silence, and the lysine producers would benefit from signing an enforceable agreement not to produce more than 30 million pounds of lysine. But we know that in the United States and many other countries, an agreement setting the output levels of two oligopolists isn’t just unenforceable, it’s illegal. So it seems that a noncooperative equilibrium is the only possible outcome. Or is it?

Overcoming the Prisoners’ Dilemma: Repeated Interaction and Tacit Collusion

Richard and Justin are playing what is known as a one-

A firm engages in strategic behavior when it attempts to influence the future behavior of other firms.

An oligopolist usually expects to be in business for many years, and knows that a decision today about whether to cheat is likely to affect the decisions of other firms in the future. So a smart oligopolist doesn’t just decide what to do based on the effect on profit in the short run. Instead, it engages in strategic behavior, taking into account the effects of its action on the future actions of other players. And under some conditions oligopolists that behave strategically can manage to behave as if they had a formal agreement to collude.

A strategy of tit for tat involves playing cooperatively at first, then doing whatever the other player did in the previous period.

Suppose that our two firms expect to be in the lysine business for many years and therefore expect to play the game of cheat versus collude many times. Would they really betray each other time and again? Probably not. Suppose that each firm considers two strategies. In one strategy, it always cheats, producing 40 million pounds of lysine each year, regardless of what the other firm does. In the other strategy, it starts with good behavior, producing only 30 million pounds in the first year, and watches to see what its rival does. If the other firm also keeps its production down, each firm will stay cooperative, producing 30 million pounds again for the next year. But if one firm produces 40 million pounds, the other firm will take the gloves off and also produce 40 million pounds the following year. This latter strategy—

Playing “tit for tat” is a form of strategic behavior because it is intended to influence the future actions of other players. The “tit for tat” strategy offers a reward to the other player for cooperative behavior—

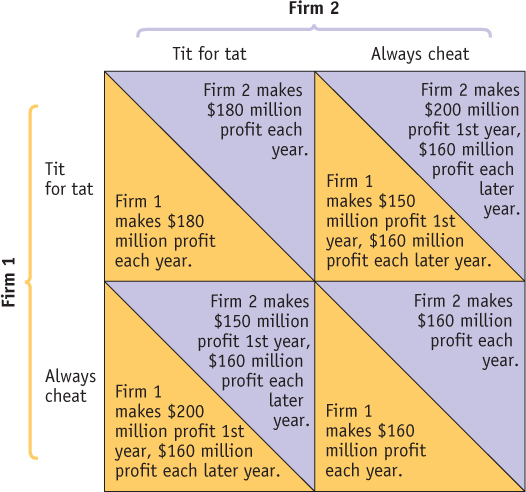

The payoff to each firm of each of these strategies would depend on which strategy the other chooses. Consider the four possibilities, shown in Figure 66.1:

If one firm plays “tit for tat” and so does the other, both firms will make a profit of $180 million each year.

If one firm plays “always cheat” but the other plays “tit for tat,” one makes a profit of $200 million the first year but only $160 million per year thereafter.

If one firm plays “tit for tat” but the other plays “always cheat,” one makes a profit of only $150 million in the first year but $160 million per year thereafter.

If one firm plays “always cheat” and the other does the same, both firms will make a profit of $160 million each year.

Which strategy is better? In the first year, one firm does better playing “always cheat,” whatever its rival’s strategy: it assures itself that it will get either $200 million or $160 million. (Which of the two payoffs it actually receives depends on whether the other plays “tit for tat” or “always cheat.”) This is better than what it would get in the first year if it played “tit for tat”: either $180 million or $150 million. But by the second year, a strategy of “always cheat” gains the firm only $160 million per year for the second and all subsequent years, regardless of the other firm’s actions. Over time, the total amount gained by playing “always cheat” is less than the amount gained by playing “tit for tat”: for the second and all subsequent years, it would never get any less than $160 million and would get as much as $180 million if the other firm played “tit for tat” as well. Which strategy, “always cheat” or “tit for tat,” is more profitable depends on two things: how many years each firm expects to play the game and what strategy its rival follows.

If the firm expects the lysine business to end in the near future, it is in effect playing a one-

| Figure 66.1 | How Repeated Interaction Can Support Collusion |

But if the firm expects to be in the business for a long time and thinks the other firm is likely to play “tit for tat,” it will make more profits over the long run by playing “tit for tat,” too. It could have made some extra short-

When firms limit production and raise prices in a way that raises each other’s profits, even though they have not made any formal agreement, they are engaged in tacit collusion.

The lesson of this story is that when oligopolists expect to compete with each other over an extended period of time, each individual firm will often conclude that it is in its own best interest to be helpful to the other firms in the industry. So it will restrict its output in a way that raises the profit of the other firms, expecting them to return the favor. Despite the fact that firms have no way of making an enforceable agreement to limit output and raise prices (and are in legal jeopardy if they even discuss prices), they manage to act “as if” they had such an agreement. When this type of unspoken agreement comes about, we say that the firms are engaging in tacit collusion.

Business decisions in real life are nowhere near as simple as those in our lysine story; nonetheless, in most oligopolistic industries, most of the time, the sellers do appear to succeed in keeping prices above their noncooperative level. Tacit collusion, in other words, is the normal state of oligopoly.