Controversies About Product Differentiation

Up to this point, we have assumed that products are differentiated in a way that corresponds to some real desire of consumers. There is real convenience in having a gas station in your neighborhood; Chinese food and Mexican food are really different from each other.

In the real world, however, some instances of product differentiation can seem puzzling if you think about them. What is the real difference between Crest and Colgate toothpaste? Between Energizer and Duracell batteries? Or a Marriott and a Hilton hotel room? Most people would be hard-

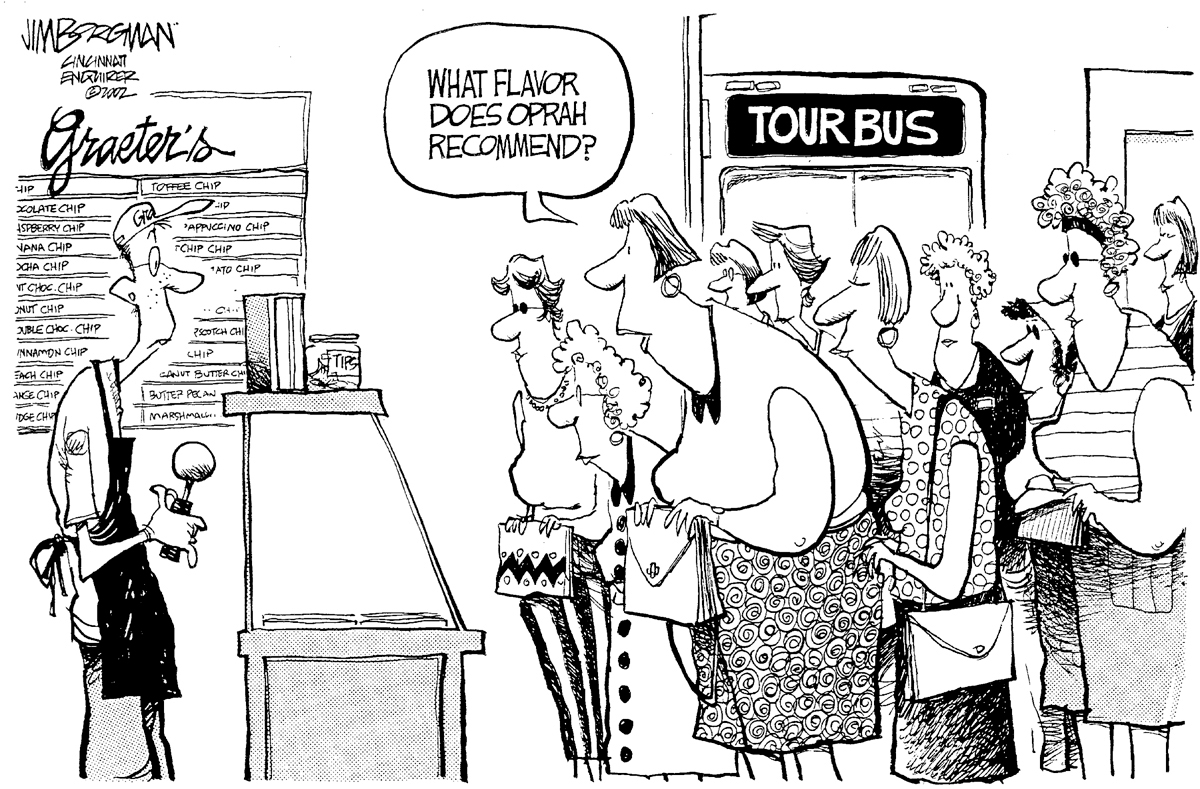

No discussion of product differentiation is complete without spending at least a bit of time on the two related issues—

The Role of Advertising

Wheat farmers don’t advertise their wares on TV, but car dealers do. That’s not because farmers are shy and car dealers are outgoing; it’s because advertising is worthwhile only in industries in which firms have at least some market power. The purpose of advertisements is to persuade people to buy more of a seller’s product at the going price. A perfectly competitive firm, which can sell as much as it likes at the going market price, has no incentive to spend money persuading consumers to buy more. Only a firm that has some market power, and which therefore charges a price that is above marginal cost, can gain from advertising. (Industries that are more or less perfectly competitive, like the milk industry, do advertise—

AP® Exam Tip

Advertising and brand name development are forms of nonprice competition that competitors use to modify consumers’ perceptions about their products in order to gain more sales.

Given that advertising “works,” it’s not hard to see why firms with market power would spend money on it. But the big question about advertising is, why does it work? A related question is whether advertising, from society’s point of view, is a waste of resources.

Not all advertising poses a puzzle. Much of it is straightforward: it’s a way for sellers to inform potential buyers about what they have to offer (or, occasionally, for buyers to inform potential sellers about what they want). Nor is there much controversy about the economic usefulness of ads that provide information: the real estate ad that declares “sunny, charming, 2 bedrooms, 1 bath, a/c” tells you things you need to know (even if a few euphemisms are involved—

But what information is being conveyed when a TV actress proclaims the virtues of one or another toothpaste or a sports hero declares that some company’s batteries are better than those inside that pink mechanical rabbit? Surely nobody believes that the sports star is an expert on batteries—

Why are consumers influenced by ads that do not really provide any information about the product? One answer is that consumers are not as rational as economists typically assume. Perhaps consumers’ judgments, or even their tastes, can be influenced by things that economists think ought to be irrelevant, such as which company has hired the most charismatic celebrity to endorse its product. And there is surely some truth to this. Consumer rationality is a useful working assumption; it is not an absolute truth.

However, another answer is that consumer response to advertising is not entirely irrational because ads can serve as indirect “signals” in a world in which consumers don’t have good information about products. To take a common example, suppose that you need to avail yourself of some local service that you don’t use regularly—

The same principle may partly explain why ads feature celebrities. You don’t really believe that the supermodel prefers that watch; but the fact that the watch manufacturer is willing and able to pay her fee tells you that it is a major company that is likely to stand behind its product. According to this reasoning, an expensive advertisement serves to establish the quality of a firm’s products in the eyes of consumers.

The possibility that it is rational for consumers to respond to advertising also has some bearing on the question of whether advertising is a waste of resources. If ads work by manipulating only the weak-

Brand Names

You’ve been driving all day, and you decide that it’s time to find a place to sleep. On your right, you see a sign for the Bates Motel; on your left, you see a sign for a Motel 6, or a Best Western, or some other national chain. Which one do you choose?

Unless they were familiar with the area, most people would head for the chain. In fact, most motels in the United States are members of major chains; the same is true of most fast-

A brand name is a name owned by a particular firm that distinguishes its products from those of other firms.

Motel chains and fast-

In fact, companies often go to considerable lengths to defend their brand names, suing anyone else who uses them without permission. You may talk about blowing your nose on a kleenex or xeroxing a term paper, but unless the product in question comes from Kleenex or Xerox, legally the seller must describe it as a facial tissue or a photocopier.

As with advertising, with which they are closely linked, the social usefulness of brand names is a source of dispute. Does the preference of consumers for known brands reflect consumer irrationality? Or do brand names convey real information? That is, do brand names create unnecessary market power, or do they serve a real purpose?

As in the case of advertising, the answer is probably some of both. On the one hand, brand names often do create unjustified market power. Consumers often pay more for brand-

On the other hand, for many products the brand name does convey information. A traveler arriving in a strange town can be sure of what awaits in a Holiday Inn or a McDonald’s; a tired and hungry traveler may find this preferable to trying an independent hotel or restaurant that might be better—

In addition, brand names offer some assurance that the seller is engaged in repeated interaction with its customers and so has a reputation to protect. If a traveler eats a bad meal at a restaurant in a tourist trap and vows never to eat there again, the restaurant owner may not care, since the chance is small that the traveler will be in the same area again in the future. But if that traveler eats a bad meal at McDonald’s and vows never to eat at a McDonald’s again, that matters to the company. This gives McDonald’s an incentive to provide consistent quality, thereby assuring travelers that quality controls are in place.