The Economy’s Factors of Production

AP® Exam Tip

The factors of production are sometimes referred to as inputs on the AP® exam.

You may recall that we have already defined a factor of production in the context of the circular-

What are these factors of production, and why do factor prices matter?

The Factors of Production

Physical capital—often referred to simply as “capital”—consists of manufactured productive resources such as equipment, buildings, tools, and machines.

Human capital is the improvement in labor created by education and knowledge that is embodied in the workforce.

Economists divide factors of production into four principal classes. The first is labor, the work done by human beings. The second is land, which encompasses resources provided by nature. The third is capital, which can be divided into two categories: physical capital—often referred to simply as “capital”—consists of manufactured productive resources such as equipment, buildings, tools, and machines. In the modern economy, human capital, the improvement in labor created by education and knowledge, and embodied in the workforce, is at least equally significant. Technological progress has boosted the importance of human capital and made technical sophistication essential to many jobs, thus helping to create the premium for workers with advanced degrees. The final factor of production, entrepreneurship, is a unique resource that is not purchased in an easily identifiable factor market like the other three. It refers to innovation and risk-

Why Factor Prices Matter: The Allocation of Resources

689

The factor prices determined in factor markets play a vital role in the important process of allocating resources among firms.

Consider the example of Mississippi and Louisiana in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, the costliest hurricane ever to hit the U.S. mainland. The states had an urgent need for workers in the building trades—

In other words, the market for a factor of production—

The demand for a factor is a derived demand. It results from (that is, it is derived from) the demand for the output being produced.

In this sense factor markets are similar to goods markets, which allocate goods among consumers. But there are two features that make factor markets special. Unlike in a goods market, demand in a factor market is what we call derived demand. That is, demand for the factor is derived from demand for the firm’s output. The second feature is that factor markets are where most of us get the largest shares of our income (government transfers being the next largest source of income in the economy).

Factor Incomes and the Distribution of Income

Most American families get the majority of their income in the form of wages and salaries—

The factor distribution of income is the division of total income among land, labor, capital, and entrepreneurship.

Obviously, then, the prices of factors of production have a major impact on how the economic “pie” is sliced among different groups. For example, a higher wage rate, other things equal, means that a larger proportion of the total income in the economy goes to people who derive their income from labor and less goes to those who derive their income from capital, land, or entrepreneurship. Economists refer to how the economic pie is sliced as the “distribution of income.” Specifically, factor prices determine the factor distribution of income—how the total income of the economy is divided among labor, land, capital, and entrepreneurship.

The factor distribution of income in the United States has been quite stable over the past few decades. In other times and places, however, large changes have taken place in the factor distribution. One notable example: during the Industrial Revolution, the share of total income earned by landowners fell sharply, while the share earned by capital owners rose.

The Factor Distribution of Income in the United States

690

When we talk about the factor distribution of income, what are we talking about in practice?

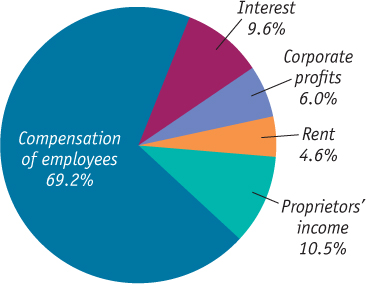

In the United States, as in all advanced economies, payments to labor account for most of the economy’s total income. Figure 69.1 shows the factor distribution of income in the United States in 2013: in that year, 69.2% of total income in the economy took the form of “compensation of employees”—a number that includes both wages and benefits such as health insurance. This number has been quite stable over the long run; 41 years earlier, in 1972, compensation of employees was very similar, at 72.2% of total income.

Much of what we call compensation of employees is really a return on human capital. A surgeon isn’t just supplying the services of a pair of ordinary hands (at least the patient hopes not!): that individual is also supplying the result of many years and hundreds of thousands of dollars invested in training and experience. We can’t directly measure what fraction of wages is really a payment for education and training, but many economists believe that labor resources created through additional human capital have become the most important factor of production in modern economies.