The Supply Curve

AP® Exam Tip

A change in demand does not affect the supply schedule, and it does not affect the supply curve, which represents the supply schedule on a graph. A change in demand does cause a change in the price, so it will affect the quantity supplied by causing a movement along the supply curve.

Some parts of the world are especially well suited to growing cotton, and the United States is one of those. But even in the United States, some land is better suited to growing cotton than other land. Whether American farmers restrict their cotton-

The quantity supplied is the actual amount of a good or service people are willing to sell at some specific price.

So just as the quantity of cotton that consumers want to buy depends on the price they have to pay, the quantity that producers are willing to produce and sell—

The Supply Schedule and the Supply Curve

A supply schedule shows how much of a good or service producers would supply at different prices.

The table in Figure 6.1 shows how the quantity of cotton made available varies with the price—

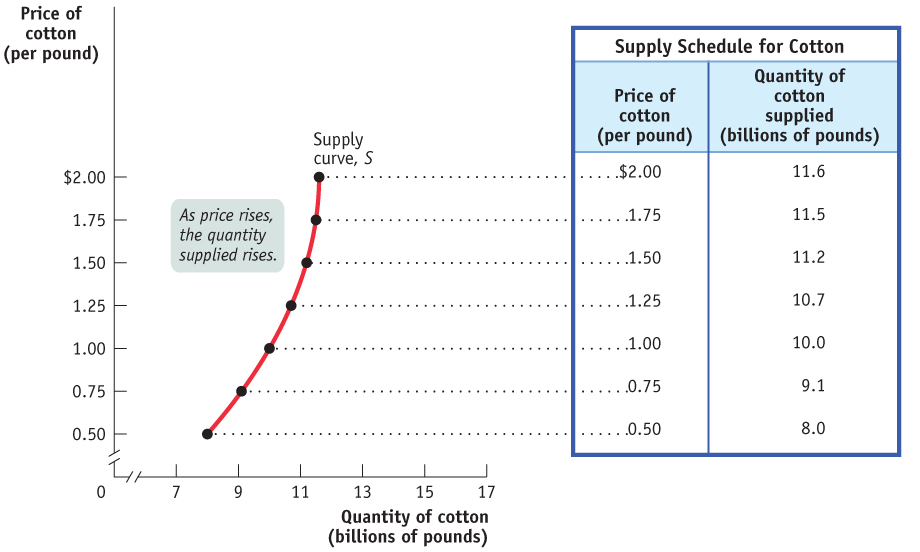

| Figure 6.1 | The Supply Schedule and the Supply Curve |

A supply schedule works the same way as the demand schedule shown in Figure 5.1: in this case, the table shows the number of pounds of cotton farmers are willing to sell at different prices. At a price of $0.50 per pound, farmers are willing to sell only 8 billion pounds of cotton per year. At $0.75 per pound, they’re willing to sell 9.1 billion pounds. At $1, they’re willing to sell 10 billion pounds, and so on.

A supply curve shows the relationship between the quantity supplied and the price.

In the same way that a demand schedule can be represented graphically by a demand curve, a supply schedule can be represented by a supply curve, as shown in Figure 6.1. Each point on the curve represents an entry from the table.

The law of supply says that, other things being equal, the price and quantity supplied of a good are positively related.

Suppose that the price of cotton rises from $1 to $1.25; we can see that the quantity of cotton farmers are willing to sell rises from 10 billion to 10.7 billion pounds. This is the normal situation for a supply curve, that a higher price leads to a higher quantity supplied. Some economists refer to this positive relationship as the law of supply. So just as demand curves normally slope downward, supply curves normally slope upward: the higher the price being offered, the more of any good or service producers will be willing to sell.

Shifts of the Supply Curve

AP® Exam Tip

The supply curve itself shows the relationship between the price and the quantity supplied, so you should not shift the supply curve to show the effect of a change in the price. When there is a change in a nonprice determinant of supply, such as production costs or the number of firms, supply changes and the supply curve shifts.

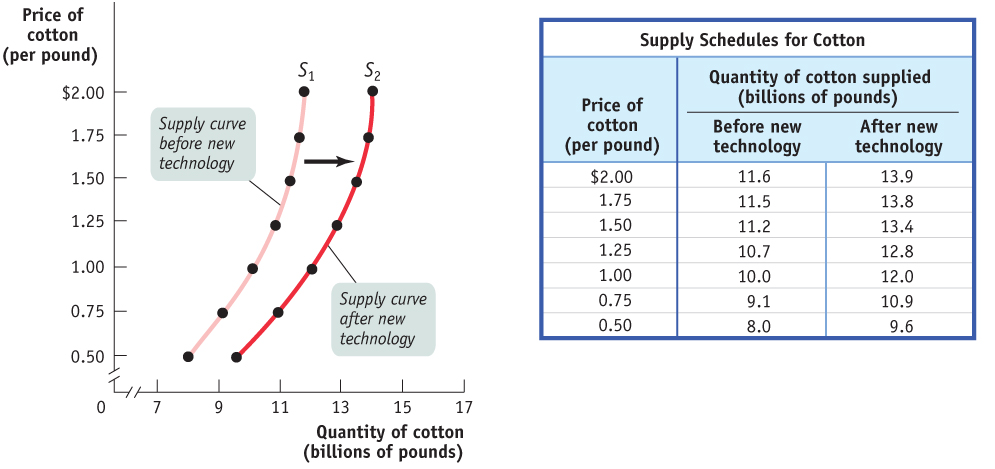

Until recently, cotton remained relatively cheap over the past several decades. One reason is that the amount of land cultivated for cotton expanded over 35% from 1945 to 2007. However, the major factor accounting for cotton’s relative cheapness was advances in the production technology, with output per acre more than quadrupling from 1945 to 2007. Figure 6.2 illustrates these events in terms of the supply schedule and the supply curve for cotton.

| Figure 6.2 | An Increase in Supply |

A change in supply is a shift of the supply curve, which changes the quantity supplied at any given price.

The table in Figure 6.2 shows two supply schedules. The schedule before improved cotton-

A movement along the supply curve is a change in the quantity supplied of a good arising from a change in the good’s price.

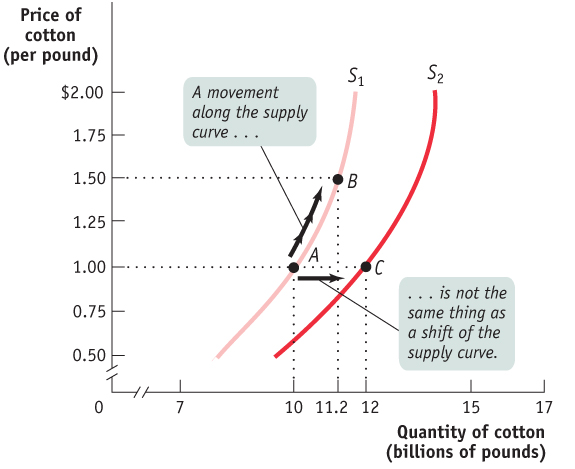

As in the analysis of demand, it’s crucial to draw a distinction between such changes in supply and movements along the supply curve—changes in the quantity supplied arising from a change in price. We can see this difference in Figure 6.3. The movement from point A to point B is a movement along the supply curve: the quantity supplied rises along S1 due to a rise in price. Here, a rise in price from $1 to $1.50 leads to a rise in the quantity supplied from 10 billion to 11.2 billion pounds of cotton. But the quantity supplied can also rise when the price is unchanged if there is an increase in supply—

| Figure 6.3 | A Movement Along the Supply Curve Versus a Shift of the Supply Curve |

Understanding Shifts of the Supply Curve

AP® Exam Tip

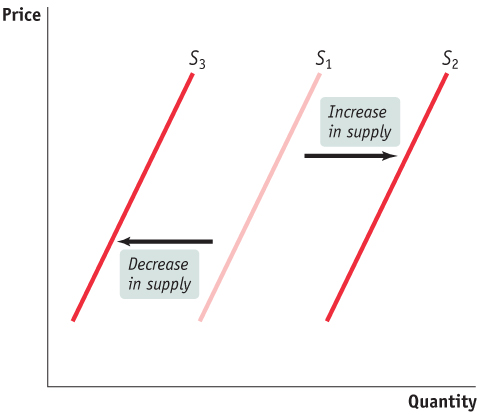

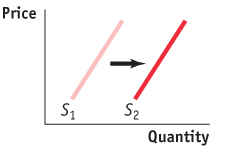

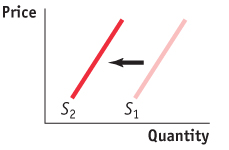

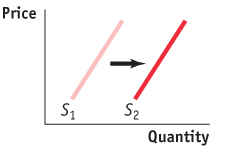

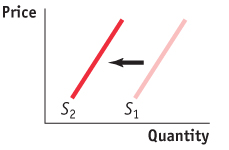

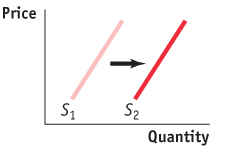

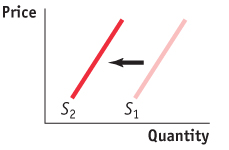

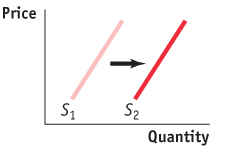

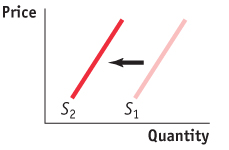

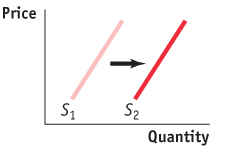

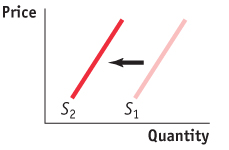

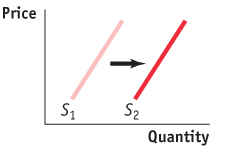

Looks can be deceiving. An increase in supply is not a shift down; it is a shift to the right, indicating an increase in the quantity supplied at every price. A decrease in supply is not a shift up, but a shift to the left, indicating a decrease in the quantity supplied at every price.

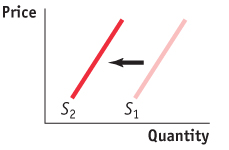

Figure 6.4 illustrates the two basic ways in which supply curves can shift. When economists talk about an “increase in supply,” they mean a rightward shift of the supply curve: at any given price, producers supply a larger quantity of the good than before. This is shown in Figure 6.4 by the rightward shift of the original supply curve S1 to S2. And when economists talk about a “decrease in supply,” they mean a leftward shift of the supply curve: at any given price, producers supply a smaller quantity of the good than before. This is represented by the leftward shift of S1 to S3.

| Figure 6.4 | Shifts of the Supply Curve |

Shifts of the supply curve for a good or service are mainly the result of five factors (though, as in the case of demand, there are other possible causes):

Changes in input prices

Changes in the prices of related goods or services

Changes in technology

Changes in expectations

Changes in the number of producers

An input is a good or service that is used to produce another good or service.

Changes in Input Prices To produce output, you need inputs. For example, to make vanilla ice cream, you need vanilla beans, cream, sugar, and so on. An input is any good or service that is used to produce another good or service. Inputs, like outputs, have prices. And an increase in the price of an input makes the production of the final good more costly for those who produce and sell it. So producers are less willing to supply the final good at any given price, and the supply curve shifts to the left. For example, fuel is a major cost for airlines. When oil prices surged in 2007–

Changes in the Prices of Related Goods or Services A single producer often produces a mix of goods rather than a single product. For example, an oil refinery produces gasoline from crude oil, but it also produces heating oil and other products from the same raw material. When a producer sells several products, the quantity of any one good it is willing to supply at any given price depends on the prices of its other co-

This effect can run in either direction. An oil refiner will supply less gasoline at any given price when the price of heating oil rises, shifting the supply curve for gasoline to the left. But it will supply more gasoline at any given price when the price of heating oil falls, shifting the supply curve for gasoline to the right. This means that gasoline and other co-

In contrast, due to the nature of the production process, other goods can be complements in production. For example, producers of crude oil—

Changes in Technology When economists talk about “technology,” they don’t necessarily mean high technology—

Improvements in technology enable producers to spend less on inputs yet still produce the same output. When a better technology becomes available, reducing the cost of production, supply increases, and the supply curve shifts to the right. As we have already mentioned, improved technology enabled farmers to more than quadruple cotton output per acre planted over the past several decades. Improved technology is the main reason that, until recently, cotton remained relatively cheap even as worldwide demand grew.

Changes in Expectations Just as changes in expectations can shift the demand curve, they can also shift the supply curve. When suppliers have some choice about when they put their good up for sale, changes in the expected future price of the good can lead a supplier to supply less or more of the good today.

For example, consider the fact that gasoline and other oil products are often stored for significant periods of time at oil refineries before being sold to consumers. In fact, storage is normally part of producers’ business strategy. Knowing that the demand for gasoline peaks in the summer, oil refiners normally store some of their gasoline produced during the spring for summer sale. Similarly, knowing that the demand for heating oil peaks in the winter, they normally store some of their heating oil produced during the fall for winter sale. In each case, there’s a decision to be made between selling the product now versus storing it for later sale. Which choice a producer makes depends on a comparison of the current price versus the expected future price. This example illustrates how changes in expectations can alter supply: an increase in the anticipated future price of a good or service reduces supply today, a leftward shift of the supply curve. But a fall in the anticipated future price increases supply today, a rightward shift of the supply curve.

An individual supply curve illustrates the relationship between quantity supplied and price for an individual producer.

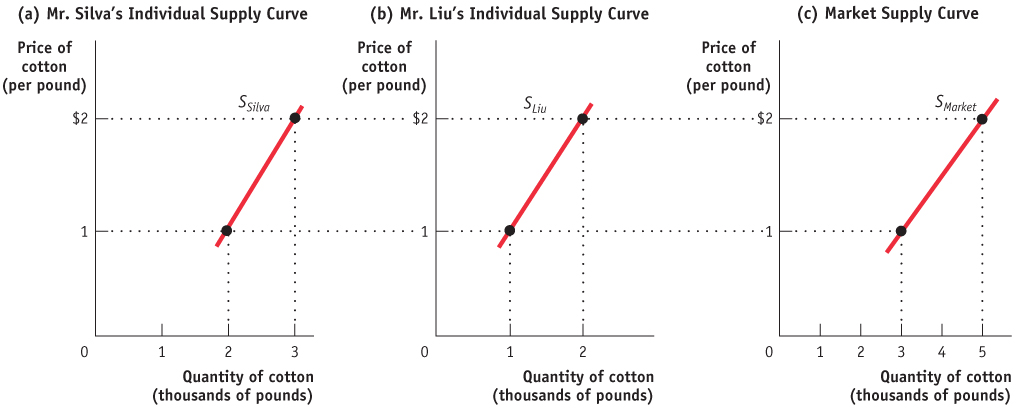

Changes in the Number of Producers Just as changes in the number of consumers affect the demand curve, changes in the number of producers affect the supply curve. Let’s examine the individual supply curve, by looking at panel (a) in Figure 6.5. The individual supply curve shows the relationship between quantity supplied and price for an individual producer. For example, suppose that Mr. Silva is a Brazilian cotton farmer and that panel (a) of Figure 6.5 shows how many pounds of cotton he will supply per year at any given price. Then SSilva is his individual supply curve.

| Figure 6.5 | Individual Supply Curves and the Market Supply Curve |

AP® Exam Tip

A mnemonic to help you remember the factors that shift supply is I-

The market supply curve shows how the combined total quantity supplied by all individual producers in the market depends on the market price of that good. Just as the market demand curve is the horizontal sum of the individual demand curves of all consumers, the market supply curve is the horizontal sum of the individual supply curves of all producers. Assume for a moment that there are only two producers of cotton, Mr. Silva and Mr. Liu, a Chinese cotton farmer. Mr. Liu’s individual supply curve is shown in panel (b). Panel (c) shows the market supply curve. At any given price, the quantity supplied to the market is the sum of the quantities supplied by Mr. Silva and Mr. Liu. For example, at a price of $2 per pound, Mr. Silva supplies 3,000 pounds of cotton per year and Mr. Liu supplies 2,000 pounds per year, making the quantity supplied to the market 5,000 pounds.

Clearly, the quantity supplied to the market at any given price is larger with Mr. Liu present than it would be if Mr. Silva were the only supplier. The quantity supplied at a given price would be even larger if we added a third producer, then a fourth, and so on. So an increase in the number of producers leads to an increase in supply and a rightward shift of the supply curve.

For an overview of the factors that shift supply, see Table 6.1.

Table 6.1 Factors That Shift Supply

| When this happens . . . | . . . supply increases | But when this happens . . . | . . . supply decreases |

| When the price of an input falls . . . |

|

When the price of an input rises . . . |

|

| When the price of a substitute in production falls . . . |

|

When the price of a substitute in production rises . . . |

|

| When the price of a complement in production rises . . . |

|

When the price of a complement in production falls . . . |

|

| When the technology used to produce the good improves . . . |

|

When the best technology used to produce the good is no longer available . . . |

|

| When the price is expected to fall in the future . . . |

|

When the price is expected to rise in the future . . . |

|

| When the number of producers rises . . . |

|

When the number of producers falls . . . |

|

Only Creatures Small and Pampered

Only Creatures Small and Pampered

During the 1970s, British television featured a popular show titled All Creatures Great and Small. It chronicled the real life of James Herriot, a country veterinarian who tended to cows, pigs, sheep, horses, and the occasional house pet, often under arduous conditions, in rural England during the 1930s. The show made it clear that, in those days, the local vet was a critical member of farming communities, saving valuable farm animals and helping farmers survive financially. And it was also clear that Mr. Herriot considered his life’s work well spent.

But that was then and this is now. According to a recent article in the New York Times, the United States has experienced a severe decline in the number of farm veterinarians over the past two decades. The source of the problem is competition. As the number of household pets has increased and the incomes of pet owners have grown, the demand for pet veterinarians has increased sharply. As a result, vets are being drawn away from the business of caring for farm animals into the more lucrative business of caring for pets. As one vet stated, she began her career caring for farm animals but changed her mind after “doing a C-

How can we translate this into supply and demand curves? Farm veterinary services and pet veterinary services are like gasoline and fuel oil: they’re related goods that are substitutes in production. A veterinarian typically specializes in one type of practice or the other, and that decision often depends on the going price for the service. America’s growing pet population, combined with the increased willingness of doting owners to spend on their companions’ care, has driven up the price of pet veterinary services. As a result, fewer and fewer veterinarians have gone into farm animal practice. So the supply curve of farm veterinarians has shifted leftward—

In the end, farmers understand that it is all a matter of dollars and cents: they get fewer veterinarians because they are unwilling to pay more. As one farmer, who had recently lost an expensive cow due to the unavailability of a veterinarian, stated, “The fact that there’s nothing you can do, you accept it as a business expense now. You didn’t used to. If you have livestock, sooner or later you’re going to have deadstock.” (Although we should note that this farmer could have chosen to pay more for a vet who would then have saved his cow.)