Equilibrium in the Labor Market

Now that we have discussed the labor supply curve, we can use the supply and demand curves for labor to determine the equilibrium wage and level of employment in the labor market.

The Decline of the Summer Job

The Decline of the Summer Job

Come summertime, resort towns along the New Jersey shore find themselves facing a recurring annual problem: a serious shortage of lifeguards. Traditionally, lifeguard positions, together with many other seasonal jobs, have been filled mainly by high school and college students. But in recent years a growing number of young Americans have chosen not to take summer jobs. In 1979, 71% of Americans between the ages of 16 and 19 were in the summer workforce. Twenty years later that number had fallen to 63%; and by 2013, it was 34.5%. Data show that young men in particular have become much less willing to take summer jobs.

One explanation for the decline in the summer labor supply is that more students feel they should devote their summers to additional study. But an important factor in the decline is increasing household affluence. As a result, many teenagers no longer feel pressured to contribute to household finances by taking a summer job; that is, the income effect leads to a reduced labor supply. Another factor points to the substitution effect: increased competition from immigrants, who are now doing the jobs typically done by teenagers (mowing lawns, delivering pizzas), has led to a decline in wages. So many teenagers forgo summer work and consume leisure instead.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

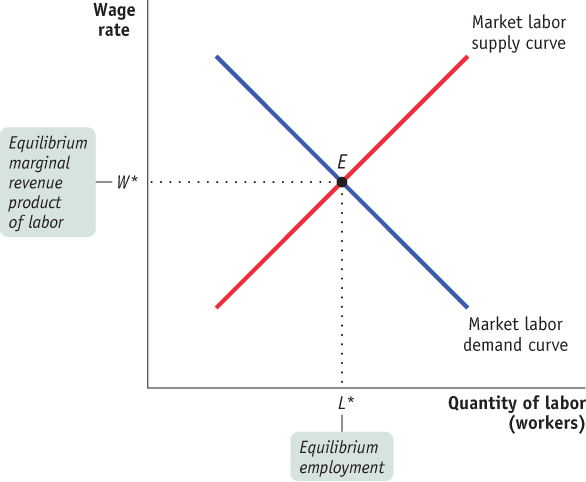

Figure 71.2 illustrates the labor market as a whole. The market labor demand curve, like the market demand curve for a good, is the horizontal sum of all the individual labor demand curves of all the firms that hire labor. And recall that a firm’s labor demand curve is the same as its marginal revenue product of labor curve. As discussed above, the labor supply curve is upward-

| Figure 71.2 | Equilibrium in the Labor Market |

The equilibrium wage rate is the wage rate at which the quantity of labor supplied is equal to the quantity of labor demanded. In Figure 71.2, this leads to an equilibrium wage rate of W* and the corresponding equilibrium employment level of L*. The equilibrium wage rate is also known as the market wage rate.

So far we have assumed that the labor market is perfectly competitive, but that isn’t always the case. Next we’ll examine the workings of an imperfectly competitive labor market.

When the Labor Market Is Not Perfectly Competitive

The marginal factor cost is the additional cost of employing an additional unit of a factor of production.

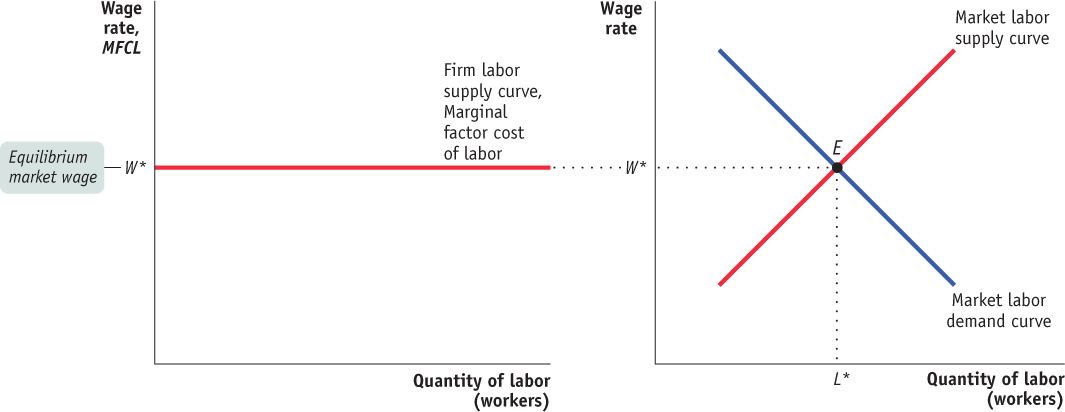

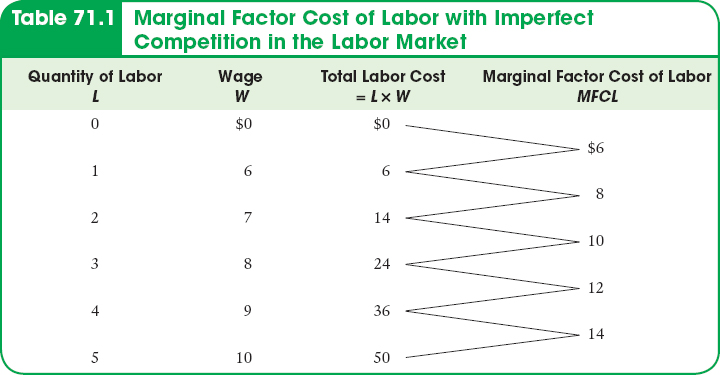

There are important differences when considering an imperfectly competitive factor market rather than a perfectly competitive market. One major difference is the marginal factor cost. The marginal factor cost is the additional cost of employing one more unit of a factor of production. For example, the marginal factor cost of labor (MFCL) is the additional cost of hiring one more unit of labor. With perfect competition in the labor market, each firm is so small that it can hire as much labor as it wants at the market wage. The firm’s hiring decision does not affect the market. This means that with perfect competition in the labor market, the additional cost of hiring another worker (the MFCL) is always equal to the market wage, and each firm faces a horizontal labor supply curve, as shown in Figure 71.3.

| Figure 71.3 | Firm Labor Supply in a Perfectly Competitive Labor Market |

A monopsonist is a single buyer in a factor market. A market in which there is a monopsonist is a monopsony.

A firm faces a very different labor supply curve in a labor market characterized by imperfect competition: it is upward-

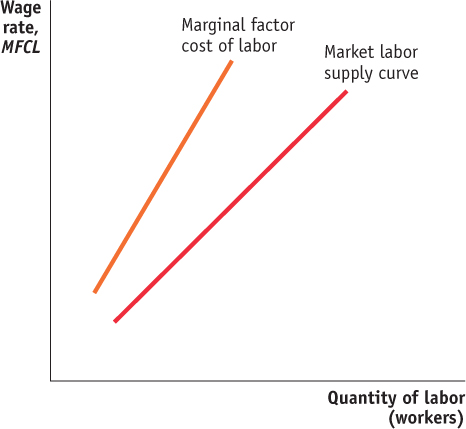

The fact that a firm in an imperfectly competitive labor market must raise the wage to hire more workers means that the MFCL curve is above the labor supply curve, as shown in Figure 71.4. The explanation for this is similar to the explanation for why the monopolist’s marginal revenue curve is below the demand curve. To sell one more, the monopolist has to lower the price, so the additional revenue is the price minus the losses on the units that would otherwise sell at the higher price. Here, to hire an additional worker, the monopolist has to raise the wage, so the marginal factor cost is the wage plus the wage increase for those workers who could otherwise be hired at the lower wage.

| Figure 71.4 | Supply of Labor and Marginal Factor Cost in an Imperfectly Competitive Market |

Equilibrium in the Imperfectly Competitive Labor Market

In a perfectly competitive labor market, firms hire labor until the marginal revenue product of labor equals the market wage. With imperfect competition in a factor market, a firm will hire additional workers until the marginal revenue product of labor equals the marginal factor cost of labor. Note that the marginal factor cost of labor in a perfectly competitive labor market is the market wage, so the term marginal factor cost is generally applicable to the analysis of hiring decisions in both perfectly competitive and imperfectly competitive labor markets. The term we used previously, wage, only applies in the specific case of perfect competition in the labor market. Thus, we can generalize and say that every firm hires workers up to the point at which the marginal revenue product of labor equals the marginal factor cost of labor:

(71-

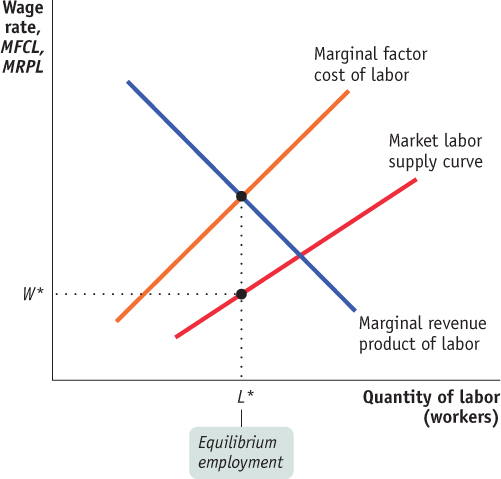

Equilibrium in the labor market with imperfect competition is shown in Figure 71.5. Once an imperfectly competitive firm has determined the optimal number of workers to hire, L*, it finds the wage necessary to hire that number of workers by starting at the point on the labor supply curve above the optimal number of workers, and looking straight to the left to see the wage level at that point, W*.

| Figure 71.5 | Equilibrium in the Labor Market with Imperfect Competition |

Let’s put the information we just learned together, again referring to Figure 71.5: In an imperfectly competitive labor market, the firm must offer a higher wage to hire more workers, so the marginal factor cost curve is above the labor supply curve. The equilibrium quantity of labor is found where the marginal revenue product equals the marginal factor cost, as represented by L* on the graph. The firm will pay the wage required to hire L* workers, which is found on the supply curve above L*. The labor supply curve shows that the quantity of labor supplied is equal to L* at a wage of W*. The equilibrium wage in the market is thus W*. Note that, unlike the wage in a perfectly competitive labor market, the wage in the imperfectly competitive labor market is less than the marginal factor cost of labor.

In Modules 69–