Private Goods—and Others

What’s the difference between installing a new bathroom in a house and building a municipal sewage system? What’s the difference between growing wheat and fishing in the open ocean?

These aren’t trick questions. In each case there is a basic difference in the characteristics of the goods involved. Bathroom appliances and wheat have the characteristics necessary to allow markets to work efficiently. Public sewage systems and fish in the sea do not.

Let’s look at these crucial characteristics and why they matter.

Characteristics of Goods

Goods like bathroom fixtures and wheat have two characteristics that are essential if a good is to be provided in efficient quantities by a market economy.

A good is excludable if the supplier of that good can prevent people who do not pay from consuming it.

A good is rival in consumption if the same unit of the good cannot be consumed by more than one person at the same time.

A good that is both excludable and rival in consumption is a private good.

When a good is nonexcludable, the supplier cannot prevent consumption by people who do not pay for it.

A good is nonrival in consumption if more than one person can consume the same unit of the good at the same time.

They are excludable: suppliers of the good can prevent people who don’t pay from consuming it.

- Page 753

They are rival in consumption: the same unit of the good cannot be consumed by more than one person at the same time.

When a good is both excludable and rival in consumption, it is called a private good. Wheat is an example of a private good. It is excludable: the farmer can sell a bushel to one consumer without having to provide wheat to everyone in the county. And it is rival in consumption: if I eat bread baked with a farmer’s wheat, that wheat cannot be consumed by someone else.

Not all goods possess these two characteristics. Some goods are nonexcludable—the supplier cannot prevent consumption of the good by people who do not pay for it. Fire protection is one example: a fire department that puts out fires before they spread protects the whole city, not just people who have made contributions to the Firemen’s Benevolent Association. An improved environment is another: pollution can’t be ended for some users of a river while leaving the river foul for others.

Nor are all goods rival in consumption. Goods are nonrival in consumption if more than one person can consume the same unit of the good at the same time. TV programs are nonrival in consumption: your decision to watch a show does not prevent other people from watching the same show.

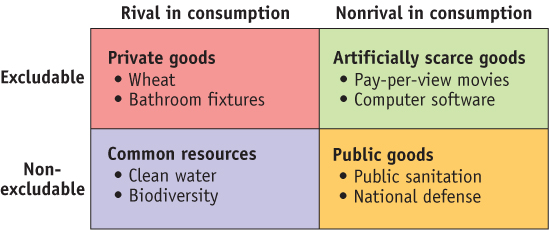

Because goods can be either excludable or nonexcludable, and either rival or nonrival in consumption, there are four types of goods, illustrated by the matrix in Figure 76.1:

| Figure 76.1 | Four Types of Goods |

Private goods, which are excludable and rival in consumption, like wheat

Public goods, which are nonexcludable and nonrival in consumption, like a public sewer system

Common resources, which are nonexcludable but rival in consumption, like clean water in a river

Artificially scarce goods, which are excludable but nonrival in consumption, like pay-

per- view movies on cable TV

AP® Exam Tip

Be prepared to classify goods according to the four different types for the AP® exam.

Of course there are many other characteristics that distinguish between types of goods—

Why Markets Can Supply Only Private Goods Efficiently

As we learned in earlier modules, markets are typically the best means for a society to deliver goods and services to its members; that is, markets are efficient except in the case of market power, externalities, or other instances of market failure. One source of market failure is rooted in the nature of the good itself: markets cannot supply goods and services efficiently unless they are private goods—

To see why excludability is crucial, suppose that a farmer had only two choices: either produce no wheat or provide a bushel of wheat to every resident of the county who wants it, whether or not that resident pays for it. It seems unlikely that anyone would grow wheat under those conditions.

Goods that are nonexcludable suffer from the free-

Yet the operator of a public sewage system consisting of pipes that anyone can dump sewage into faces pretty much the same problem as our hypothetical farmer. A sewage system makes the whole city cleaner and healthier—

Because of the free-

Goods that are excludable and nonrival in consumption, like pay-

Now we can see why private goods are the only goods that will be produced and consumed in efficient quantities in a competitive market. (That is, a private good will be produced and consumed in efficient quantities in a market free of market power, externalities, and other sources of market failure.) Because private goods are excludable, producers can charge for them and so have an incentive to produce them. And because they are also rival in consumption, it is efficient for consumers to pay a positive price—

Yet there are crucial goods that don’t meet these criteria—