Common Resources

A common resource is nonexcludable and rival in consumption: you can’t stop others from consuming the good, and when they consume it, less of the good is available for you.

A common resource is a good that is nonexcludable but is rival in consumption. An example is the stock of fish in a fishing area, like the fisheries off the coast of New England. Traditionally, anyone who had a boat could go out to sea and catch fish—

Other examples of common resources include clean air, water, and the diversity of animal and plant species on the planet (biodiversity). In each of these cases the fact that the good is rival in consumption, and yet nonexcludable, poses a serious problem.

The Problem of Overuse

AP® Exam Tip

For the AP® exam, you should be able to explain and identify solutions to the overuse of common resources.

Overuse is the depletion of a common resource that occurs when individuals ignore the fact that their use depletes the amount of the resource remaining for others.

Because common resources are nonexcludable, individuals cannot be charged for their use. But the resources are rival in consumption, so an individual who uses a unit depletes the resource by making that unit unavailable to others. As a result, a common resource is subject to overuse: an individual will continue to use it until his or her marginal private benefit is equal to his or her marginal private cost, ignoring the cost that this action inflicts on society as a whole.

Fish are a classic example of a common resource. Particularly in heavily fished waters, each fisher’s catch imposes a cost on others by reducing the fish population and making it harder for others to catch fish. But fishers have no personal incentive to take this cost into account. As a result, from society’s point of view, too many fish are caught. Traffic congestion is another example of overuse of a common resource. A major highway during rush hour can accommodate only a certain number of vehicles per hour. Each person who decides to drive to work alone, rather than carpool or work at home, causes many other people to have a longer commute; but there is no incentive for individual drivers to take these consequences into account.

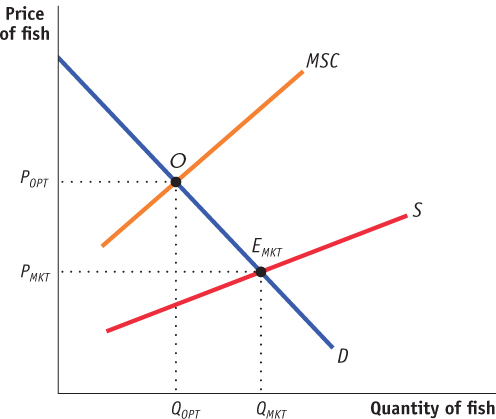

In the case of a common resource, as in the earlier examples involving marginal external costs, the marginal social cost of your use of that resource is higher than your marginal private cost, the cost to you of using an additional unit of the good. Figure 76.3 illustrates this point. It shows the demand curve for fish, which measures the marginal private benefit of fish (as well as the marginal social benefit because there are no external benefits from catching and consuming fish). The figure also shows the supply curve for fish, which measures the marginal private cost of production in the fishing industry. We know that the industry supply curve is the horizontal sum of each individual fisher’s supply curve—

| Figure 76.3 | A Common Resource |

As we noted, there is a close parallel between the problem of managing a common resource and the problem posed by negative externalities. In the case of an activity that generates a negative externality, the marginal social cost of production is greater than the marginal private cost of production, the difference being the marginal external cost imposed on society. Here, the loss to society arising from a fisher’s depletion of the common resource plays the same role as the external cost when there is a negative externality. In fact, many negative externalities (such as pollution) can be thought of as involving common resources (such as clean air).

The Efficient Use and Maintenance of a Common Resource

Because common resources pose problems similar to those created by negative externalities, the solutions are also similar. To ensure efficient use of a common resource, society must find a way to get individual users of the resource to take into account the costs they impose on others. This is the same principle as that of getting individuals to internalize a negative externality that arises from their actions.

There are three principal ways to induce people who use common resources to internalize the costs they impose on others:

Tax or otherwise regulate the use of the common resource

Create a system of tradable licenses for the right to use the common resource

Make the common resource excludable and assign property rights to some individuals

The first two solutions overlap with the approaches to private goods with negative externalities. Just as governments use Pigouvian excise taxes to temper the consumption of alcohol, they use alternative forms of Pigouvian taxes to reduce the use of common resources. For example, in some countries there are “congestion charges” on those who drive during rush hour, in effect charging them for the use of highway space, a common resource. Likewise, visitors to national parks in the United States must pay an entry fee that is essentially a Pigouvian tax.

A second way to correct the problem of overuse is to create a system of tradable licenses for the use of the common resource, much like the tradable emissions permit systems designed to address negative externalities. The policy maker issues the number of licenses that corresponds to the efficient level of use of the good. For example, hundreds of fisheries around the world have adopted individual transferable quotas that are effectively licenses to catch a certain quantity of fish. Making the licenses tradable ensures that the right to use the good is allocated efficiently—

But when it comes to common resources, often the most natural solution is simply to assign property rights. At a fundamental level, common resources are subject to overuse because nobody owns them. The essence of ownership of a good—