Antitrust Policy

As we discussed in Module 66, imperfect competition first became an issue in the United States during the second half of the nineteenth century when industrialists formed trusts to facilitate monopoly pricing. By having shareholders place their shares in the hands of a board of trustees, major companies in effect merged into a single firm. That is, they created monopolies.

Eventually, there was a public backlash, driven partly by concern about the economic effects of the trust movement and partly by fear that the owners of the trusts were simply becoming too powerful. The result was the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, which was intended both to prevent the creation of more monopolies and to break up existing ones. Following the Sherman Act, the government passed several other acts intended to clarify antitrust policy.

The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890

AP® Exam Tip

You should be able to recognize the important pieces of antitrust legislation in case they appear in the multiple choice section of the AP® exam.

When Microsoft Corporation bundled its Internet Explorer web browser software with its Windows operating system, the makers of competing Netscape Navigator cried foul. Netscape advocates claimed the immediate availability of Internet Explorer to Windows users would create unfair competition. The plaintiffs sought protection under the cornerstone of U.S. antitrust policy (known in many other countries as “competition policy”), the Sherman Antitrust Act. This Act was the first of three major federal antitrust laws in the United States, followed by the Clayton Antitrust Act and the Federal Trade Commission Act, both passed in 1914. The Department of Justice, which has an Antitrust Division charged with enforcing antitrust laws, describes the goals of antitrust laws as protecting competition, ensuring lower prices, and promoting the development of new and better products. It emphasizes that firms in competitive markets attract consumers by cutting prices and increasing the quality of products or services. Competition and profit opportunities also stimulate businesses to find new and more efficient production methods.

The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 has two important provisions, each of which outlaws a particular type of activity. The first provision makes it illegal to create a contract, combination, or conspiracy that unreasonably restrains interstate trade. The second provision outlaws the monopolization of any part of interstate commerce. In addition, under the law, the Department of Justice is empowered to bring civil claims and criminal prosecutions when the law is violated. Indeed, it was the Department of Justice that filed suit against Microsoft in the web browser case. The initial court ruling, by the way, was that Microsoft should be broken up into one company that sold Windows and another that sold other software components. After that ruling was overturned on appeal, a final settlement kept Microsoft intact, but prohibited various forms of predatory behavior and practices that could create barriers to entry.

As the ambiguities of the Microsoft case suggest, the law provides little detail regarding what constitutes “restraining trade.” And the law does not make it illegal to be a monopoly but to “monopolize,” that is, to take illegal actions to become a monopoly. If you are the only firm in an industry because no other firm chooses to enter the market, you are not in violation of the Sherman Act.

The two provisions of the Sherman Act give very broad, general descriptions of the activities it makes illegal. The act does not provide details regarding specific actions or activities that it prohibits. The vague nature of the Sherman Act led to the subsequent passage of two additional major antitrust laws.

The Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914

The Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914 was intended to clarify the Sherman Act, which did not identify specific firm behaviors that were illegal. The Clayton Act outlaws four specific firm behaviors: price discrimination, anticompetitive practices, anticompetitive mergers and acquisitions, and interlocking directorates (two corporate boards of directors that share at least one director in common).

You are already familiar with the topic of price discrimination from our discussion of market structures. The Clayton Act makes it illegal to charge different prices to different customers for the same product. Obviously, there are exceptions to this rule that allow the price discrimination we see in practice, for example, at movie theaters where children pay a different price than adults.

By prohibiting the anticompetitive practice of exclusive dealing, the Clayton Act makes it illegal for a firm to refuse to do business with you just because you also do business with its competitors. If a firm had the dominant product in a given market, exclusive dealing could allow it to gain monopoly power in other markets. For example, a company that sells an extremely popular felt-

The Clayton Act also outlaws tying arrangements because, otherwise, a firm could expand its monopoly power for a dominant product by “tying” the purchase of one product to the purchase of a dominant product in another market. Tying arrangements occur when a firm stipulates that it will sell you a specific product, say a printer, only if you buy something else, such as printer paper, at the same time. In this case, tying the printer and paper together expands the firm’s printer market power into the market for paper. In this way, as with exclusive dealing, tying arrangements can lessen competition by allowing a firm to expand its market power from one market into another.

Mergers and acquisitions happen fairly often in the U.S. economy; most are not illegal despite the Clayton Act stipulations. The Justice Department regularly reviews proposed mergers between companies in the same industry and, under the Clayton Act, bars any that they determine would significantly reduce competition. To evaluate proposed mergers, they often use the measures we discussed in the oligopoly modules: concentration ratios and the Herfindahl–

The Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914

Passed in 1914, the Federal Trade Commission Act prohibits unfair methods of competition in interstate commerce and created the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to enforce the Act. The FTC Act outlaws unfair competition, including “unfair or deceptive acts.” The FTC Act also outlaws some of the same practices included in the Sherman and Clayton Acts. In addition, it specifically outlaws price fixing (including the setting of minimum resale prices), output restrictions, and actions that prevent the entry of new firms. The FTC’s goal is to promote lower prices, higher output, and free entry—

Dealing with Natural Monopoly

Antitrust laws are designed to promote competition by preventing business behaviors that concentrate market power. But what if a market is a natural monopoly? As you will recall, a natural monopoly occurs when economies of scale make it efficient to have only one firm in a market. Now we turn from promoting competition to establishing a monopoly, but seeking a public policy to prevent the relatively high prices and low quantities that result when there is only one firm.

Breaking up a monopoly that isn’t natural is clearly a good idea: the gains to consumers outweigh the loss to the firm. But what about the situation in which a large firm has a lower average total cost than many small firms—

While there are a few examples of public ownership in the United States, such as Amtrak, a provider of passenger rail service, the more common answer has been to leave the industry in private hands but subject it to regulation.

Price Regulation Most local utilities are natural monopolies with regulated prices. By having only one firm produce in the market, society benefits from increased efficiency. That is, the average cost of production is lower due to economies of scale. But without price regulation, the natural monopoly would be tempted to restrict its output and raise its price. How, then, do regulators determine an appropriate price?

Marginal cost pricing occurs when regulators set a monopoly’s price equal to its marginal cost to achieve efficiency.

Since the purpose of regulation is to achieve efficiency in the market, a logical place to set the price is at the level at which the marginal cost curve intersects the demand curve. This is called marginal cost pricing. (Because we are no longer discussing situations with externalities, we will refer to a single marginal cost that is both the marginal social cost and the marginal private cost.) We have seen that it is allocatively efficient for a firm to set its price equal to its marginal cost. So should regulators require marginal cost pricing?

AP® Exam Tip

Understanding the different pricing options for a regulated natural monopoly is a key skill for the AP® exam. You may need to graph and explain marginal cost pricing and average cost pricing.

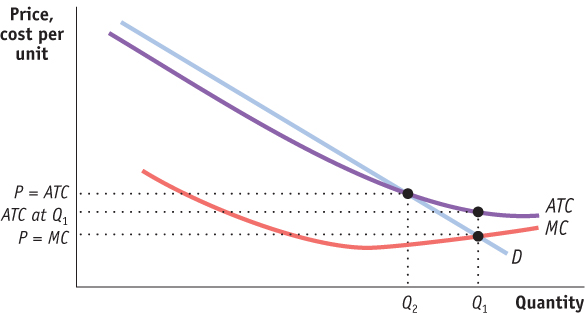

Figure 77.1 illustrates this situation. In the case of a natural monopoly, the firm is operating on the downward-

| Figure 77.1 | Price Setting for a Regulated Monopoly |

Average cost pricing occurs when regulators set a monopoly’s price equal to its average cost to prevent the firm from incurring a loss.

If regulators want to set the price so that the firm does not require a subsidy, they can set the price at which the demand curve intersects the average total cost curve and the firm breaks even. This is called average cost pricing. As Figure 77.1 illustrates, average cost pricing results in output level Q2. The result, a lower quantity at a higher price than with marginal cost pricing, seems to fly in the face of what antitrust regulation is all about. But remember that there are always trade-

Allowing a natural monopoly to exist permits the firm to produce at a lower average total cost than if multiple firms produced in the same market. And price regulation seeks to prevent the inefficiency that results when an unregulated monopoly limits its output and raises its price. This all looks terrific: consumers are better off, monopoly profits are avoided, and overall welfare increases. Unfortunately, things are rarely that easy in practice. The main problem is that regulators don’t always have the information required to set the price exactly at the level at which the demand curve crosses the average total cost curve. Sometimes they set it too low, creating shortages; at other times they set it too high, increasing inefficiency. Also, regulated monopolies, like publicly owned firms, tend to exaggerate their costs to regulators and to provide inferior quality to consumers.

The Regulated Price of Power

The Regulated Price of Power

Power doesn’t come cheap, and we’re not just talking about the nearly $2 billion spent on congressional races in 2012. By 2017, Georgia Power plans to add two 1,100-

On October 6, 2010, U.S. Interior Secretary Ken Salazar and representatives from Cape Wind Associates signed the lease for a wind farm off the coast of Massachusetts. The $2.5 billion project will generate 468 megawatts of electricity. With lower output and higher start-

Why the interest in generating energy from wind when energy from coal is cheaper for the consumer? The dynamics of supply and demand provide one reason: as supplies of coal decrease and energy demand increases, the equilibrium price for coal energy will rise, helping investments in wind energy to pay off. Another reason relates to the external costs discussed in Module 75: wind turbines create no emissions. The U.S. Department of Energy reports that if 20 percent of the nation’s energy needs were satisfied with wind, carbon dioxide emissions would fall by 825 million metric tons annually. Like coal-