Supply, Demand, and Equilibrium

We have now covered the first three key elements in the supply and demand model: the demand curve, the supply curve, and the set of factors that shift each curve. The next step is to put these elements together to show how they can be used to predict the actual price at which the good is bought and sold, as well as the actual quantity transacted.

An economic situation is in equilibrium when no individual would be better off doing something different.

In competitive markets this interaction of supply and demand tends to move toward what economists call equilibrium. Imagine a busy afternoon at your local supermarket; there are long lines at the checkout counters. Then one of the previously closed registers opens. The first thing that happens is a rush to the newly opened register. But soon enough things settle down and shoppers have rearranged themselves so that the line at the newly opened register is about as long as all the others. This situation—

AP® Exam Tip

Equilibrium is a term you will hear often throughout the course. When a market is in equilibrium, the quantity supplied equals the quantity demanded. There are no shortages or surpluses pushing the price up or down, and therefore there is no tendency for the price or the quantity to change.

A competitive market is in equilibrium when the price has moved to a level at which the quantity demanded of a good equals the quantity supplied of that good. The price at which this takes place is the equilibrium price, also referred to as the market-

The concept of equilibrium helps us understand the price at which a good or service is bought and sold as well as the quantity transacted of the good or service. A competitive market is in equilibrium when the price has moved to a level at which the quantity of a good demanded equals the quantity of that good supplied. At that price, no individual seller could make herself better off by offering to sell either more or less of the good and no individual buyer could make himself better off by offering to buy more or less of the good. Recall the shoppers at the supermarket who cannot make themselves better off (cannot save time) by changing lines. Similarly, at the market equilibrium, the price has moved to a level that exactly matches the quantity demanded by consumers to the quantity supplied by sellers.

The price that matches the quantity supplied and the quantity demanded is the equilibrium price; the quantity bought and sold at that price is the equilibrium quantity. The equilibrium price is also known as the market-

Finding the Equilibrium Price and Quantity

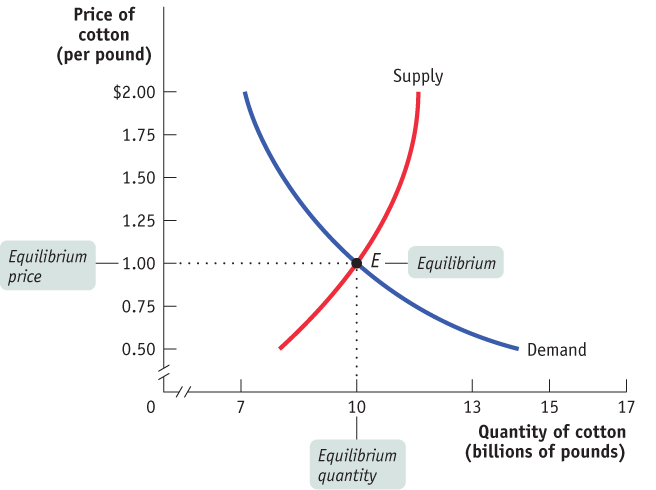

The easiest way to determine the equilibrium price and quantity in a market is by putting the supply curve and the demand curve on the same diagram. Since the supply curve shows the quantity supplied at any given price and the demand curve shows the quantity demanded at any given price, the price at which the two curves cross is the equilibrium price: the price at which quantity supplied equals quantity demanded.

Figure 7.1 combines the demand curve from Figure 5.1 and the supply curve from Figure 6.1. They intersect at point E, which is the equilibrium of this market; $1 is the equilibrium price and 10 billion pounds is the equilibrium quantity.

| Figure 7.1 | Market Equilibrium |

Let’s confirm that point E fits our definition of equilibrium. At a price of $1 per pound, cotton farmers are willing to sell 10 billion pounds a year and cotton consumers want to buy 10 billion pounds a year. So at the price of $1 a pound, the quantity of cotton supplied equals the quantity demanded. Notice that at any other price the market would not clear: every willing buyer would not be able to find a willing seller, or vice versa. More specifically, if the price were more than $1, the quantity supplied would exceed the quantity demanded; if the price were less than $1, the quantity demanded would exceed the quantity supplied.

The model of supply and demand, then, predicts that given the demand and supply curves shown in Figure 7.1, 10 billion pounds of cotton would change hands at a price of $1 per pound. But how can we be sure that the market will arrive at the equilibrium price? We begin by answering three simple questions:

Why do all sales and purchases in a market take place at the same price?

Why does the market price fall if it is above the equilibrium price?

Why does the market price rise if it is below the equilibrium price?

Why Do All Sales and Purchases in a Market Take Place at the Same Price?

There are some markets where the same good can sell for many different prices, depending on who is selling or who is buying. For example, have you ever bought a souvenir in a “tourist trap” and then seen the same item on sale somewhere else (perhaps even in the shop next door) for a lower price? Because tourists don’t know which shops offer the best deals and don’t have time for comparison shopping, sellers in tourist areas can charge different prices for the same good.

But in any market in which the buyers and sellers have both been around for some time, sales and purchases tend to converge at a generally uniform price, so we can safely talk about the market price. It’s easy to see why. Suppose a seller offered a potential buyer a price noticeably above what the buyer knew other people were paying. The buyer would clearly be better off shopping elsewhere—

Why Does the Market Price Fall If It Is Above the Equilibrium Price?

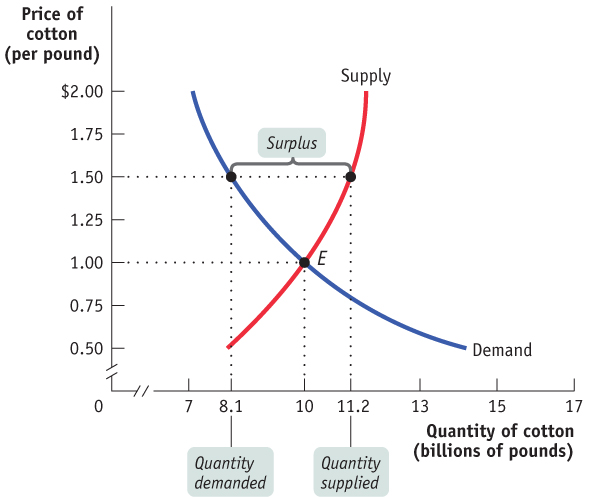

Suppose the supply and demand curves are as shown in Figure 7.1 but the market price is above the equilibrium level of $1—

| Figure 7.2 | Price Above Its Equilibrium Level Creates a Surplus |

There is a surplus of a good or service when the quantity supplied exceeds the quantity demanded. Surpluses occur when the price is above its equilibrium level.

As the figure shows, at a price of $1.50 there would be more pounds of cotton available than consumers wanted to buy: 11.2 billion pounds versus 8.1 billion pounds. The difference of 3.1 billion pounds is the surplus—also known as the excess supply—of cotton at $1.50.

This surplus means that some cotton farmers are frustrated: at the current price, they cannot find consumers who want to buy their cotton. The surplus offers an incentive for those frustrated would-

Why Does the Market Price Rise If It Is Below the Equilibrium Price?

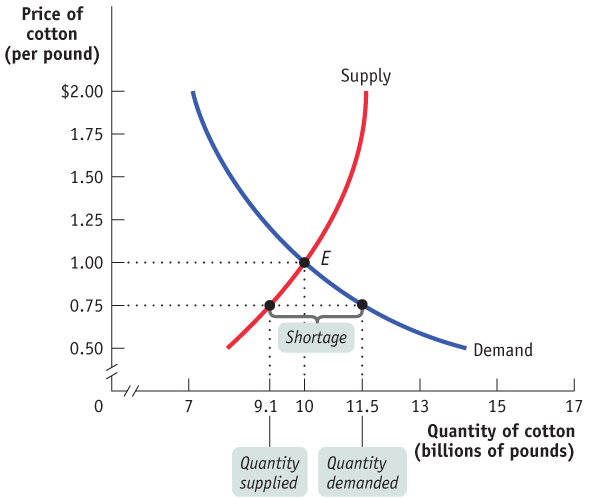

There is a shortage of a good or service when the quantity demanded exceeds the quantity supplied. Shortages occur when the price is below its equilibrium level.

Now suppose the price is below its equilibrium level—

| Figure 7.3 | Price Below Its Equilibrium Level Creates a Shortage |

The Price of Admission

The Price of Admission

The market equilibrium, so the theory goes, is pretty egalitarian because the equilibrium price applies to everyone. That is, all buyers pay the same price—

The market for concert tickets is an example that seems to contradict the theory—

Puzzling as this may seem, there is no contradiction once we take opportunity costs and tastes into account. For major events, buying tickets from the box office means waiting in very long lines. Ticket buyers who use Internet resellers have decided that the opportunity cost of their time is too high to spend waiting in line. And tickets for major events being sold at face value by online box offices often sell out within minutes. In this case, some people who want to go to the concert badly but have missed out on the opportunity to buy cheaper tickets from the online box office are willing to pay the higher Internet reseller price.

Not only that—

So the theory of competitive markets isn’t just speculation. If you want to experience it for yourself, try buying tickets to a concert.

When there is a shortage, there are frustrated would-

Using Equilibrium to Describe Markets

We have now seen that a market tends to have a single price, the equilibrium price. If the market price is above the equilibrium level, the ensuing surplus leads buyers and sellers to take actions that lower the price. And if the market price is below the equilibrium level, the ensuing shortage leads buyers and sellers to take actions that raise the price. So the market price always moves toward the equilibrium price, the price at which there is neither surplus nor shortage.