Price Ceilings

Aside from rent control, there are not many price ceilings in the United States today. But at times they have been widespread. Price ceilings are typically imposed during crises—

Believe it or not, rent control in New York is a legacy of World War II: it was imposed because wartime production created an economic boom, which increased demand for apartments at a time when the labor and raw materials that might have been used to build them were being used to win the war instead. Although most price controls were removed soon after the war ended, New York’s rent limits were retained and gradually extended to buildings not previously covered, leading to some very strange situations.

You can rent a one-

Aside from producing great deals for some renters, however, what are the broader consequences of New York’s rent control system? To answer this question, we turn to the supply and demand model.

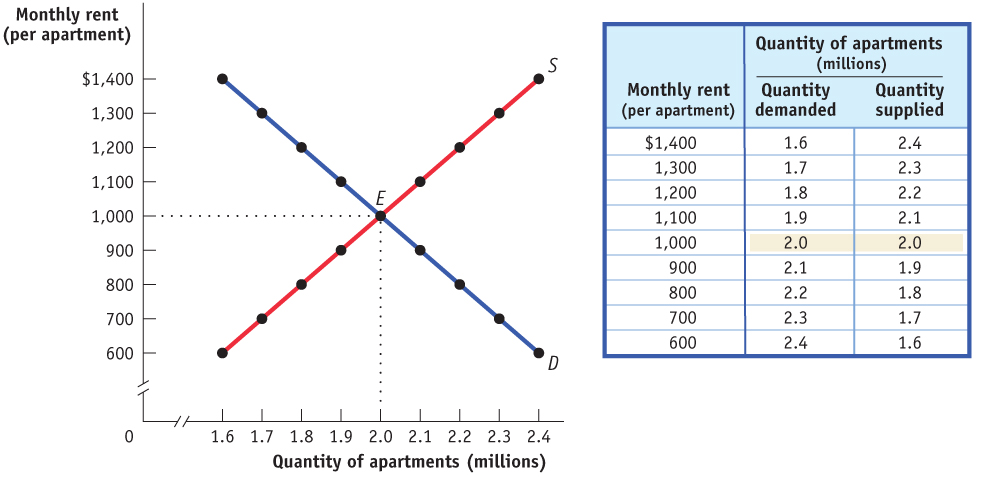

Modeling a Price Ceiling

To see what can go wrong when a government imposes a price ceiling on an efficient market, consider Figure 8.1, which shows a simplified model of the market for apartments in New York. For the sake of simplicity, we imagine that all apartments are exactly the same and so would rent for the same price in an unregulated market. The table in the figure shows the demand and supply schedules; the demand and supply curves are shown on the left. We show the quantity of apartments on the horizontal axis and the monthly rent per apartment on the vertical axis. You can see that in an unregulated market the equilibrium would be at point E: 2 million apartments would be rented for $1,000 each per month.

| Figure 8.1 | The Market for Apartments in the Absence of Government Controls |

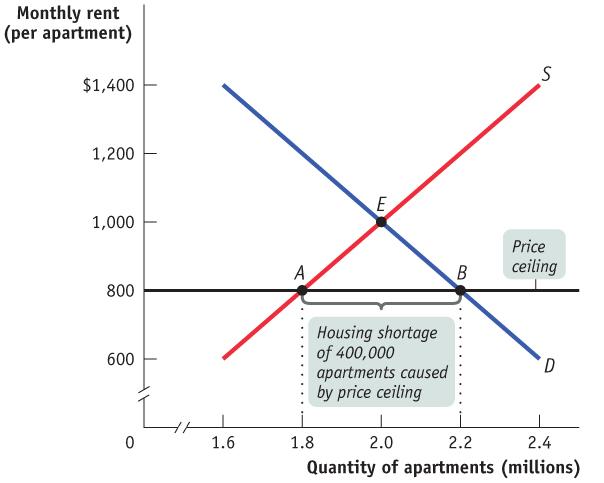

Now suppose that the government imposes a price ceiling, limiting rents to a price below the equilibrium price—

| Figure 8.2 | The Effects of a Price Ceiling |

Do price ceilings always cause shortages? No. If a price ceiling is set above the equilibrium price, it won’t have any effect. Suppose that the equilibrium rental rate on apartments is $1,000 per month and the city government sets a ceiling of $1,200. Who cares? In this case, the price ceiling won’t be binding—

Inefficient Allocation to Consumers Rent control doesn’t just lead to too few apartments being available. It can also lead to misallocation of the apartments that are available: people who badly need a place to live may not be able to find an apartment, while some apartments may be occupied by people with much less urgent needs.

Price ceilings often lead to inefficiency in the form of inefficient allocation to consumers: people who want the good badly and are willing to pay a high price don’t get it, and those who care relatively little about the good and are only willing to pay a relatively low price do get it.

In the case shown in Figure 8.2, 2.2 million people would like to rent an apartment at $800 per month, but only 1.8 million apartments are available. Of those 2.2 million who are seeking an apartment, some want an apartment badly and are willing to pay a high price to get one. Others have a less urgent need and are only willing to pay a low price, perhaps because they have alternative housing. An efficient allocation of apartments would reflect these differences: people who really want an apartment will get one and people who aren’t all that eager to find an apartment won’t. In an inefficient distribution of apartments, the opposite will happen: some people who are not especially eager to find an apartment will get one and others who are very eager to find an apartment won’t. Because people usually get apartments through luck or personal connections under rent control, it generally results in an inefficient allocation to consumers of the few apartments available.

To see the inefficiency involved, consider the plight of the Lees, a family with young children who have no alternative housing and would be willing to pay up to $1,500 for an apartment—

This allocation of apartments—

Generally, if people who really want apartments could sublease them from people who are less eager to live there, both those who gain apartments and those who trade their occupancy for money would be better off. However, subletting is illegal under rent control because it would occur at prices above the price ceiling. The fact that subletting is illegal doesn’t mean it never happens. In fact, chasing down illegal subletting is a major business for New York private investigators. A 2007 report in the New York Times described how private investigators use hidden cameras and other tricks to prove that the legal tenants in rent-

Price ceilings typically lead to inefficiency in the form of wasted resources: people expend money, effort, and time to cope with the shortages caused by the price ceiling.

Wasted Resources Another reason a price ceiling causes inefficiency is that it leads to wasted resources: people expend money, effort, and time to cope with the shortages caused by the price ceiling. Back in 1979, U.S. price controls on gasoline led to shortages that forced millions of Americans to spend hours each week waiting in lines at gas stations. The opportunity cost of the time spent in gas lines—

Price ceilings often lead to inefficiency in that the goods being offered are of inefficiently low quality: sellers offer low quality goods at a low price even though buyers would prefer a higher quality at a higher price.

Inefficiently Low Quality Yet another way a price ceiling causes inefficiency is by causing goods to be of inefficiently low quality. Inefficiently low quality means that sellers offer low-

Again, consider rent control. Landlords have no incentive to provide better conditions because they cannot raise rents to cover their repair costs but are able to find tenants easily. In many cases, tenants would be willing to pay much more for improved conditions than it would cost for the landlord to provide them—

This whole situation is a missed opportunity—

A black market is a market in which goods or services are bought and sold illegally—

Black Markets And that leads us to a last aspect of price ceilings: the incentive they provide for illegal activities, specifically the emergence of black markets. We have already described one kind of black market activity—

What’s wrong with black markets? In general, it’s a bad thing if people break any law because it encourages disrespect for the law in general. Worse yet, in this case illegal activity worsens the position of those who try to be honest. If the Lees are scrupulous about upholding the rent control law but other people—

So Why Are There Price Ceilings?

We have seen three common results of price ceilings:

a persistent shortage of the good

inefficiency arising from this persistent shortage in the form of inefficiently low quantity, inefficient allocation of the good to consumers, resources wasted in searching for the good, and the inefficiently low quality of the good offered for sale

the emergence of illegal, black market activity

Given these unpleasant consequences, why do governments still sometimes impose price ceilings? Why does rent control, in particular, persist in New York?

One answer is that although price ceilings may have adverse effects, they do benefit some people. In practice, New York’s rent control rules—

Also, when price ceilings have been in effect for a long time, buyers may not have a realistic idea of what would happen without the price ceilings. In our previous example, the rental rate in an unregulated market (Figure 8.1) would be only 25% higher than in the regulated market (Figure 8.2): $1,000 instead of $800. But how would renters know that? Indeed, they might have heard about black market transactions at much higher prices—

A last answer is that government officials often do not understand supply and demand analysis! It is a great mistake to suppose that economic policies in the real world are always sensible or well informed.

AP® Exam Tip

When it comes to price controls, the ceiling is down low and the floor is up high. That is, to have any effect, a price ceiling must be below the equilibrium price, and a price floor must be above the equilibrium price.