Psychology and Economics

In Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking, Malcolm Gladwell explains that by necessity or instinct, many decisions are made on the basis of first impressions. Snap judgments can lead to less-

Bounded Rationality

Bounded rationality describes the limits on optimal decision making that result from imperfect intelligence and the scarcity of time and information.

Dubious about models based on rationality and full information, Nobel laureate Herbert Simon explained that rationality is bounded by limitations in the ability of decision makers to formulate and solve complex problems. In Models of My Life, Simon argued that even Albert Einstein could not match the mental gymnastics ascribed to the fictional “economic man.” Simon coined the phrase bounded rationality to describe the limits on optimal decision making that result from imperfect intelligence and the scarcity of time and information. Bounded rationality causes missteps, as when a price that ends in “99” makes a consumer perceive the amount as being lower than it really is.

Simon also studied the judgmental heuristics—rules of thumb—

Neoclassical theories rest on assumptions of rationality that are sometimes at odds with observed human behavior. For example, some theories of consumer choice are valid under the assumption that the amount an individual would be willing to pay for a good and the amount he or she would accept to give up an identical good are the same. However, researchers have found endowment effects, meaning that people place a higher value on what they have than on what they don’t have. In a famous example, Daniel Kahneman, Jack Knetsch, and Richard Thaler found that, after randomly selecting half the students in a class to receive coffee mugs, students without mugs were willing to pay less than half as much to buy one as the people with a mug had to be paid to give one up.

Sticking with the Status Quo

Sticking with the Status Quo

Status quo bias causes people to stick with what they’ve got despite equally attractive alternatives. In Smart Choices, John Hammond, Ralph Keeney, and Howard Raiffa describe a natural experiment in which the state governments of New Jersey and Pennsylvania both adopted the same two options for automobile insurance, but each selected a different default plan. Under plan A, insurance premiums were lower but drivers had a limited right to litigate after an accident. Under plan B, the premiums were higher but litigation options were broader. In New Jersey, drivers received plan A unless they specified otherwise; Pennsylvania drivers were assigned to plan B unless they opted for plan A. The result was that the majority of drivers in each state stuck with the status quo, meaning that they felt the best plan was the plan they were given in the first place.

Do you experience status quo bias? Think about your family’s choice of where to live, and your favorite sports teams, politicians, and brand names. In some cases, the choice might be clear. In other cases, perhaps you’ve stuck with the status quo despite the existence of equally attractive alternatives.

Behavioral economists use the concept of loss aversion to explain evidence that consumers consider sunk costs—

Excessive Optimism Crime provides an important example of bounded rationality in the form of excessive optimism. Neoclassical models treat crime as a rational activity, the price of which is the expected punishment. This implies that more severe punishments or higher rates of apprehension or conviction will deter crime. Yet a study of the knowledge and mindset of criminals found that most criminals do not have the information required to perform cost-

Unfortunately, crime is just the tip of the iceberg of poor decisions caused by excessive optimism. Here are some additional examples:

People underestimate the risks of common but unpublicized events such as work-

related motor vehicle accidents and falls, and overestimate the risk of uncommon but dramatic, highly publicized events such as earthquakes, homicides, airplane crashes, and rare types of cancer. The result is inadequate safety precautions against the large risks and overinvestment in precautions against the small risks. Page EM-15More than half of all new businesses fail within five years, which may indicate excessive optimism among entrepreneurs. It is also possible that the potential benefits of a successful business outweigh the high risks of failure, but decision makers who underestimate the risks are prone to overinvest.

The majority of Americans believe they are smarter than average and have better-

than- average chances of winning the lottery, being professionally successful, and avoiding disease and automobile accidents. In the business world, most managers think they are more capable than the average manager. A common reason that many lawsuits go to trial is unrealistic optimism on the part of one side or both sides about the strength of their case. In a representative study, the average plaintiff’s attorney expected a jury award 27% higher than the amount anticipated by the average defense attorney.

Even when good information is available, people may not use it wisely. Because people are capable of stubbornness, bias, and misjudgment to their own downfall, the improper use of information can lead to unfortunate and inefficient resource allocations.

Framing It is standard procedure at several international hotel chains to place a card in the bathrooms of guest rooms with a message along the following lines:

Save Our Planet. Every day millions of gallons of water are used to wash towels . . . A towel on the rack means “I will use again.” Thank you for helping us conserve the Earth’s vital resources.

If the hotels were really bent on saving Earth’s resources, they would provide recycling bins, organic cotton sheets, and carpets made from recycled fibers. The pitch to avoid washing towels may have more to do with saving the financial resources of the hotels, but customer participation depends on how the appeal is framed.

Framing is the creation of context for a product or idea.

Framing is the creation of context for a product or idea, and context matters. Richard Thaler found that a typical consumer would pay no more than $1.50 for a good brand of beer from a grocery store but would pay up to $2.65 for an identical beer from a fancy hotel, even if a friend was bringing that beer to the consumer to drink at the same beach either way. Brand managers spend millions of dollars to frame their brand names because, for example, consumers perceive apparel differently after seeing Maria Sharapova wear it, and they perceive a hotel differently knowing that Brad Pitt stays there. Consumers pay more for a cup of coffee at Starbucks than at McDonald’s, not because the Starbucks coffee itself is necessarily better (a 2007 Consumer Reports taste test suggests that McDonald’s coffee is actually better), but because of the image and ambiance in which Starbucks coffee is framed.

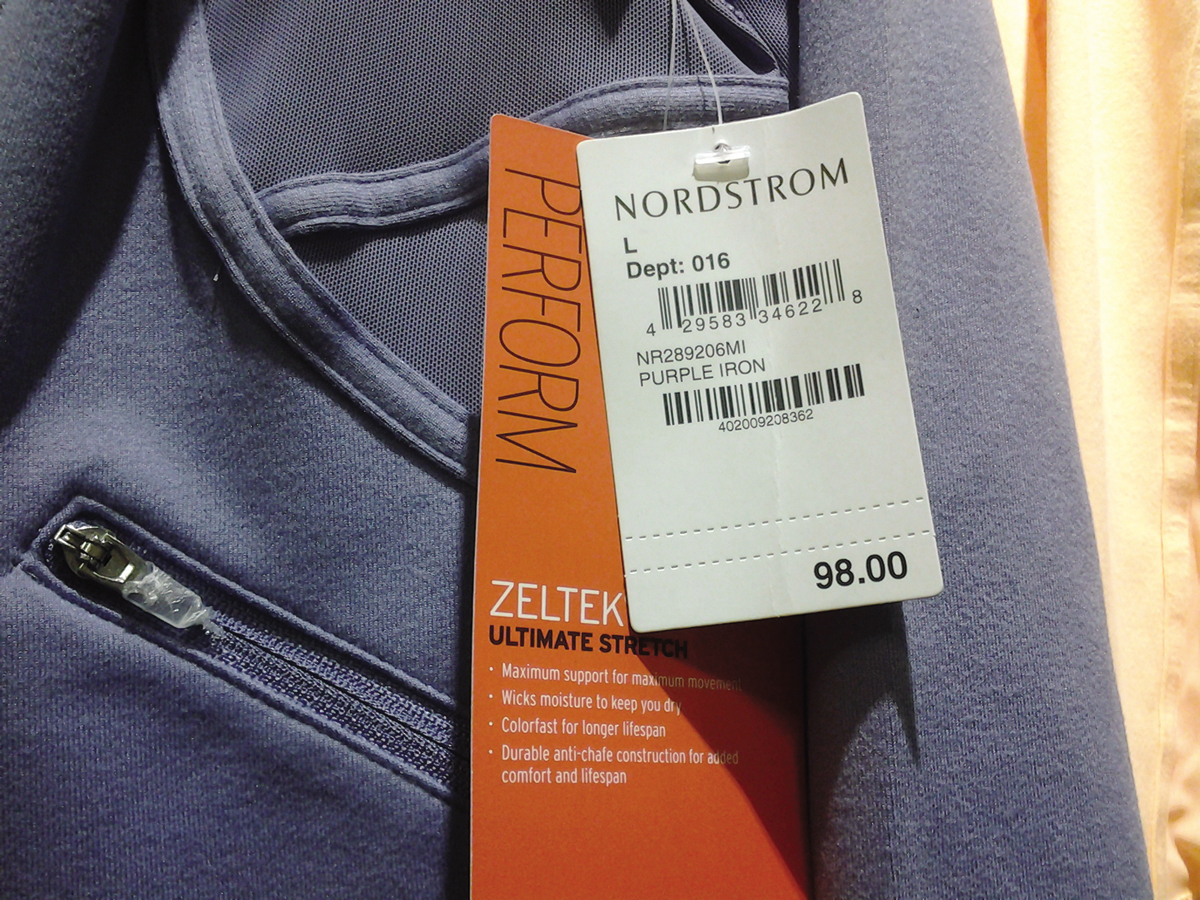

The strategy of odd or just-

Bounded Willpower

Bounded willpower is willpower constrained by limits on the determination needed to do difficult things.

It’s rational to spend money, retire, or take vacations that decrease earnings, as long as the value of the resulting benefits exceeds the value of the money forgone. Yet sometimes people forgo money in irrational ways. Bounded willpower—willpower constrained by limits on the determination needed to do difficult things—

In the analysis of behavior, it is important not to categorize everything that causes problems as irrational. Economists Gary Becker and Kevin Murphy pointed out that even the use of potentially addictive substances can be rational if the benefits outweigh the costs. They showed that people who care more about the present than the future are more prone to addiction because they discount future problems related to health, relationships, and finances when weighing them against ongoing desires for addictive substances. Becker and Murphy argue that when heavy drinkers and smokers say they want to quit but cannot, it may be a matter of the long-

While some addictions may be rational, humans are subject to temptations and emotions that can lead them astray. Anger, jealousy, frustration, and embarrassment can overcome willpower and trigger irrational responses. Take, for example, the Wendy’s customer who shot manager Renal Frage due to anger over not receiving enough packets of chili sauce. Similar examples appear frequently in the news.

Bounded Self-Interest

Bounded self-

Neoclassical economic models rest on assumptions of self-

Economists have examined the human struggle between self-

In the dictator game, the recipient has no choice but to accept the divider’s allocation. Thus, a rational, wealth-

Clearly there is more to decision making than wealth maximization. Customers may pay more for a product that causes less harm to other people or the environment, as managers at Toyota discovered when their relatively expensive but environmentally friendly Prius Hybrid flew out of showrooms faster than the company could make more. Attracting a new employee by offering a salary that eclipses the salary of existing employees can cause considerable strife due to those employees’ interests in fairness. And there may be no amount of money that can separate a parent from a needy child, as suggested by Derek Fisher’s forfeiture of the remaining three years and $21 million in his NBA contract with the Utah Jazz to be with his ill daughter in 2007.