5.2 Endogenous Taxation and the Multipliers

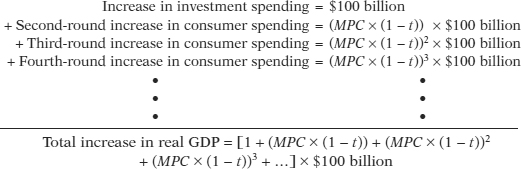

In contrast to autonomous taxation, with endogenous taxation the government captures some of the increase in real GDP. Specifically, let’s assume that the government “captures” a fraction, t, of any increase in real GDP in the form of taxes, where t, the tax rate, is a fraction between 0 and 1. And let’s repeat the exercise we carried out in Chapter 11, where we consider the effects of a $100 billion increase in investment spending. The same analysis holds for any autonomous increase in aggregate expenditure—

The $100 billion increase in investment spending initially raises real GDP by $100 billion (the first round). In the absence of taxes, disposable income would rise by $100 billion. But because part of the rise in real GDP is collected in the form of taxes, disposable income only rises by (1 − t) × $100 billion. The second-

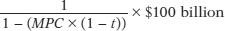

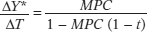

As we pointed out in Chapter 11, an infinite series of the form 1 + x + x2 + …, with 0 < x < 1, is equal to 1/(1 − x). In this example, x = (MPC × (1 − t)). So the total effect of a $100 billion increase in investment spending, taking into account all the subsequent increases in consumer spending, is to raise real GDP by:

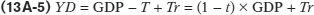

The government captures a fraction of any increase in real GDP, in the form of taxes. That is, if t is the tax rate, then T = t × GDP. Also, as stated above,

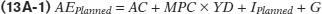

Again, since disposable income, YD, is GDP after subtracting taxes and adding transfers, then:

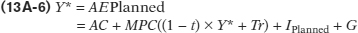

The income–

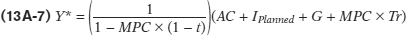

Again, with some manipulation, we get:

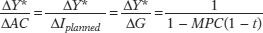

This equation gives us the following two multipliers:

the autonomous expenditure multiplier:

the autonomous transfers multiplier:

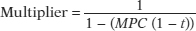

There is no autonomous taxation multiplier here since taxes now depend on income only. When we calculated the multiplier assuming away the effect of taxes, we found that it was 1/(1 − MPC). But when we assume that a fraction, t, of any change in real GDP is collected in the form of taxes, the multiplier is:

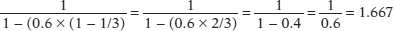

This is always a smaller number than 1/(1 − MPC), and its size diminishes as t grows. Suppose, for example, that MPC = 0.6. In the absence of taxes, this implies a multiplier of 1/(1 − 0.6) = 1/0.4 = 2.5. But now let’s assume that t = 1/3, that is, that 1/3 of any increase in real GDP is collected by the government. Then the multiplier is: