11.5 SUMMARY

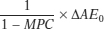

An autonomous change in aggregate expenditure leads to a chain reaction in which the total change in real GDP is equal to the multiplier times the initial change in aggregate expenditure. The size of the multiplier,

, depends on the marginal propensity to consume, MPC, the fraction of an additional dollar of disposable income spent on consumption. The larger the MPC, the larger the multiplier and the larger the change in real GDP for any given autonomous change in aggregate expenditure. The marginal propensity to save, MPS, is equal to 1 − MPC.

, depends on the marginal propensity to consume, MPC, the fraction of an additional dollar of disposable income spent on consumption. The larger the MPC, the larger the multiplier and the larger the change in real GDP for any given autonomous change in aggregate expenditure. The marginal propensity to save, MPS, is equal to 1 − MPC.The individual consumption function shows how an individual household’s consumer spending is determined by its current disposable income. The aggregate consumption function shows the relationship for the entire economy. According to the life-

cycle hypothesis, households try to smooth their consumption over their lifetimes. As a result, the aggregate consumption function shifts in response to changes in expected future disposable income and changes in aggregate wealth. Planned investment spending depends negatively on the interest rate and on existing production capacity; it depends positively on expected future real GDP. The accelerator principle says that investment spending is greatly influenced by the expected growth rate of real GDP.

Firms hold inventories of goods so that they can satisfy consumer demand quickly. Inventory investment is positive when firms add to their inventories, and negative when they reduce them. Often, however, changes in inventories are not a deliberate decision but the result of mistakes in forecasts about sales. The result is unplanned inventory investment, which can be either positive or negative. Actual investment spending is the sum of planned investment spending and unplanned inventory investment.

In income–expenditure equilibrium, planned aggregate expenditure, which in a simplified model with no government and no trade is the sum of consumer spending and planned investment spending, is equal to real GDP. At the income–expenditure equilibrium GDP, or Y*, unplanned inventory investment is zero. When real GDP is smaller than Y*, unplanned inventory investment is negative (since planned aggregate expenditure exceeds real GDP and real GDP = AEPlanned + IUnplanned); there is an unanticipated reduction in inventories and subsequently firms increase production, often by hiring more workers. When real GDP exceeds Y*, unplanned inventory investment is positive (since planned aggregate expenditure is smaller than real GDP and real GDP = AEPlanned + IUnplanned); there is an unanticipated increase in inventories and subsequently firms reduce production, usually by laying off some workers. The Keynesian cross shows how the economy self-

adjusts to income– expenditure equilibrium through inventory adjustments. After an autonomous change in planned aggregate expenditure, the inventory adjustment process moves the economy to a new income–

expenditure equilibrium. The change in income– expenditure equilibrium GDP arising from an autonomous change in spending is equal to  .

.