12.1 Aggregate Demand

The aggregate demand curve shows the relationship between the aggregate price level and the quantity of aggregate output demanded by households, businesses, the government, and the rest of the world.

The Great Depression, the great majority of economists agree, was the result of a massive negative, or adverse, demand shock. What does that mean? In Chapter 3 we explained that when economists talk about a fall in the demand for a particular good or service, they’re referring to a leftward shift of the demand curve. Similarly, when economists talk about a negative, or adverse, demand shock to the economy as a whole, they’re referring to a leftward shift of the aggregate demand curve, a curve that shows the relationship between the aggregate price level and the quantity of aggregate output demanded by households, firms, the government, and the rest of the world.

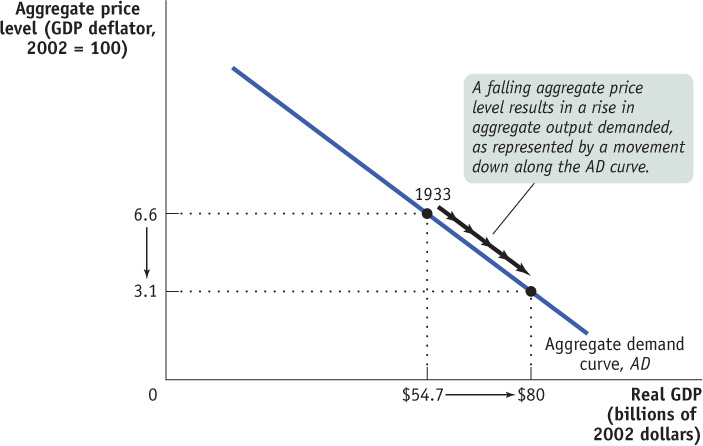

Figure 12-1 shows what the aggregate demand curve may have looked like in 1933, at the end of the 1929-1933 recession. The horizontal axis shows the total quantity of domestic goods and services demanded, measured in 2002 dollars. We use real GDP to measure aggregate output and will often use the two terms interchangeably. The vertical axis shows the aggregate price level, measured by the GDP deflator. With these variables on the axes, we can draw a curve, AD, showing how much aggregate output would have been demanded at any given aggregate price level. Since AD is meant to illustrate aggregate demand in 1933, one point on the curve corresponds to actual data for 1933, when the aggregate price level was 6.6 and the total quantity of domestic final goods and services purchased was $54.7 billion in 2002 dollars.

As drawn in Figure 12-1, the aggregate demand curve is downward sloping, indicating a negative relationship between the aggregate price level and the quantity of aggregate output demanded. A higher aggregate price level, other things equal, reduces the quantity of aggregate output demanded; a lower aggregate price level, other things equal, increases the quantity of aggregate output demanded. According to Figure 12-1, if the price level in 1933 had been 3.1 instead of 6.6, the total quantity of domestic final goods and services demanded would have been $80 billion in 2002 dollars instead of $54.7 billion.

The first key question about the aggregate demand curve is: why should the curve be downward sloping?

Why Is the Aggregate Demand Curve Downward Sloping?

In Figure 12-1, the curve AD is downward sloping. But why? Recall the basic equation of national income accounting:

(12-1) GDP = C + I + G + X − IM

where C is consumer spending, I is investment spending, G is government purchases of goods and services, X is exports to other countries, and IM is imports. If we measure these variables in constant dollars—

You might think that the downward slope of the aggregate demand curve is a natural consequence of the law of demand we defined back in Chapter 3. That is, since the demand curve for any one good is downward sloping, isn’t it natural that the demand curve for aggregate output is also downward sloping? This turns out, however, to be a misleading parallel. The demand curve for any individual good shows how the quantity demanded depends on the price of that good, holding the prices of other goods and services and income constant. The main reason the quantity of a good demanded falls when the price of that good rises—

But when we consider movements up or down the aggregate demand curve, we’re considering a simultaneous change in the prices of all final goods and services. Furthermore, changes in the composition of goods and services in consumer spending aren’t relevant to the aggregate demand curve: if consumers decide to buy fewer clothes but more cars, this doesn’t necessarily change the total quantity of final goods and services they demand.

Why, then, does a rise in the aggregate price level lead to a fall in the quantity of all domestically produced final goods and services demanded? There are two main reasons: the wealth effect and the interest rate effect of a change in the aggregate price level.

The wealth effect of a change in the aggregate price level is the effect on consumer spending caused by the effect of a change in the aggregate price level on the purchasing power of consumers’ assets.

The Wealth Effect An increase in the aggregate price level, other things equal, reduces the purchasing power of many assets. Consider, for example, someone who has $5000 in a bank account. If the aggregate price level were to rise by 25%, what used to cost $5000 would now cost $6250, and would no longer be affordable. And what used to cost $4000 would now cost $5000, so that the $5000 in the bank account would now buy only as much as $4000 would have bought previously. With the loss in purchasing power, the owner of that bank account would probably scale back his or her consumption plans. Millions of other people would respond the same way, leading to a fall in real spending on final goods and services, because a rise in the aggregate price level reduces the purchasing power of everyone’s bank account. Correspondingly, a fall in the aggregate price level increases the purchasing power of consumers’ assets and leads to more consumer demand. The wealth effect of a change in the aggregate price level is the effect on consumer spending caused by the effect of a change in the aggregate price level on the purchasing power of consumers’ assets. Because of the wealth effect, consumer spending, C, falls when the aggregate price level rises, leading to a downward-

The Interest Rate Effect Economists use the term money in its narrowest sense to refer to cash and bank deposits on which people can write cheques and do debit transactions. People and firms hold money because it reduces the cost and inconvenience of undertaking transactions. An increase in the aggregate price level, other things equal, reduces the purchasing power of a given amount of money holdings. To purchase the same basket of goods and services as before, people and firms now need to (and want to) hold more money. So, in response to an increase in the aggregate price level, the public tries to increase its money holdings, either by borrowing more or by selling assets such as bonds. This reduces the funds available for lending to other borrowers and drives interest rates up.

The interest rate effect of a change in the aggregate price level is the effect on consumer spending and investment spending caused by the effect of a change in the aggregate price level on the purchasing power of consumers’ and firms’ money holdings.

In Chapter 10 we learned that a rise in the interest rate reduces investment spending because it makes the cost of borrowing higher. It also reduces consumer spending because households save more of their disposable income. So a rise in the aggregate price level depresses investment spending, I, and consumer spending, C, owing to the rise in interest rates, which is in turn caused by the shrinking real purchasing power of money holdings. This effect is known as the interest rate effect of a change in the aggregate price level. This also leads to a downward-

We’ll have a lot more to say about money and interest rates in Chapter 15 on monetary policy. We’ll also see, in Chapter 19, which covers open-

The Aggregate Demand Curve and the Income–Expenditure Model

In the preceding chapter we introduced the income–

Recall that one of the assumptions of the income–

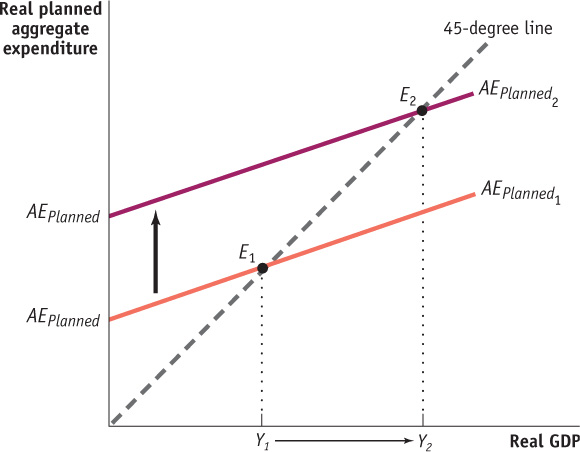

Figure 12-2 shows, once again, how income–

We’ve just seen, however, that changes in the aggregate price level change the level of real planned aggregate expenditure at any given level of real GDP. This means that when the aggregate price level changes, the AEPlanned curve shifts. For example, suppose that the aggregate price level falls. As a result of both the wealth effect and the interest rate effect, the fall in the aggregate price level will lead to higher real planned aggregate expenditure at any given level of real GDP. So the AEPlanned curve will shift up, as illustrated in Figure 12-2 by the shift from AEPlanned1 to AEPlanned2. The increase in real planned aggregate expenditure leads to the multiplier process that moves the income–

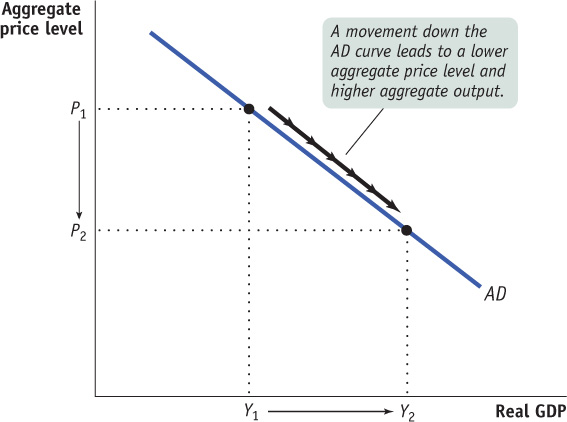

Figure 12-3 shows how this result can be used to derive the aggregate demand curve. In Figure 12-3, we show a fall in the aggregate price level from P1 to P2. We saw in Figure 12-2 that a fall in the aggregate price level would lead to an upward shift of the AEPlanned curve and hence a rise in real GDP. You can see this same result in Figure 12-3 as a movement along the AD curve: as the aggregate price level falls, real GDP rises from Y1 to Y2.

So the aggregate demand curve doesn’t replace the income–

In practice, economists often use the income–

Shifts of the Aggregate Demand Curve

In Chapter 3, where we introduced the analysis of supply and demand in the market for an individual good, we stressed the importance of the distinction between movements along the demand curve and shifts of the demand curve. The same distinction applies to the aggregate demand curve. Figure 12-1 shows a movement along the aggregate demand curve, a change in the aggregate quantity of goods and services demanded as the aggregate price level changes.

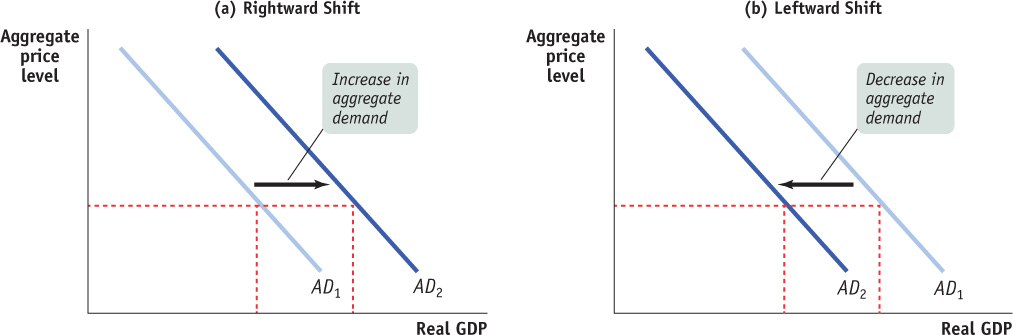

But there can also be shifts of the aggregate demand curve, changes in the quantity of goods and services demanded at any given price level, as shown in Figure 12-4. When we talk about an increase in aggregate demand, we mean a shift of the aggregate demand curve to the right, as shown in panel (a) by the shift from AD1 to AD2. A rightward shift occurs when the quantity of aggregate output demanded increases at any given aggregate price level. A decrease in aggregate demand means that the AD curve shifts to the left, as in panel (b). A leftward shift implies that the quantity of aggregate output demanded falls at any given aggregate price level.

When the aggregate demand curve shifts to the right, it is called a positive shift, since it usually has a positive impact on aggregate real income (it rises), employment (more jobs are created), and the unemployment rate (it decreases). Similarly, a shift to the left is called an adverse shift because it usually has a negative impact on aggregate real income (it decreases), employment (there are fewer jobs), and the unemployment rate (it increases). When the curve shifts unexpectedly, we refer to it as a shock. Positive AD shocks and adverse AD shocks help drive the business cycle, which refers to short-

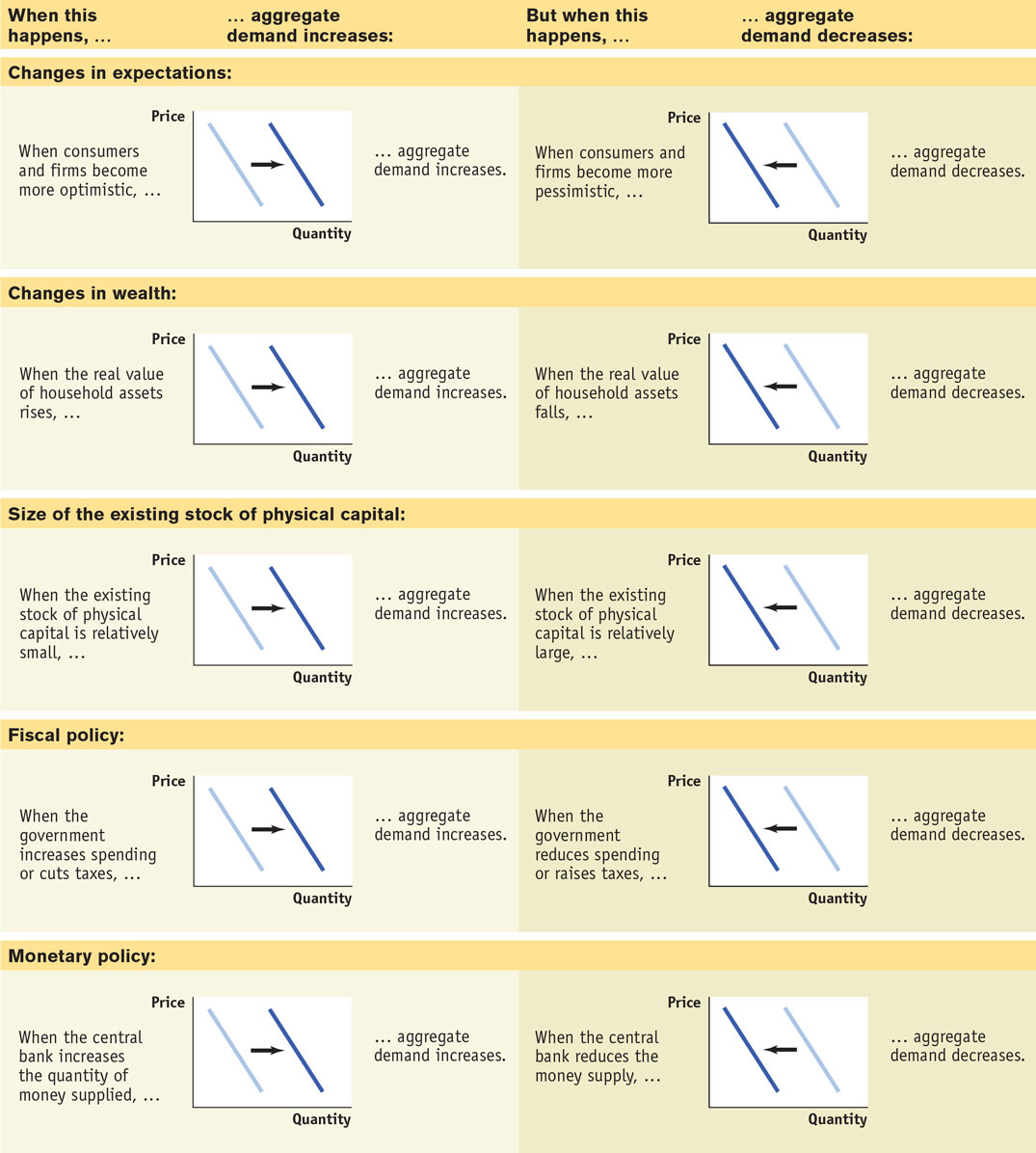

A number of factors that are unrelated to inflation can shift the aggregate demand curve. Among the most important factors are changes in expectations, changes in wealth, and the size of the existing stock of physical capital. In addition, both fiscal and monetary policy can shift the aggregate demand curve. All five factors set the multiplier process in motion. By causing an initial rise or fall in real GDP, they change disposable income, which leads to additional changes in aggregate expenditure, which lead to further changes in real GDP, and so on. For an overview of factors that shift the aggregate demand curve, see Table 12-1.

Changes in Expectations As explained in Chapter 11, both consumer spending and planned investment spending depend in part on people’s expectations about the future. Consumers base their spending not only on the income they have now but also on the income they expect to have in the future. Firms base their planned investment spending not only on current conditions but also on the sales they expect to make in the future. As a result, changes in expectations can push consumer spending and planned investment spending up or down. If consumers and firms become more optimistic, aggregate expenditure rises (perhaps due to an increase in autonomous consumption and/or autonomous investment); if they become more pessimistic, aggregate spending falls (as the increased pessimism reduces autonomous consumption and/or autonomous investment). In fact, short-

Changes in Wealth Consumer spending depends in part on the value of household assets. When the real value of these assets rises, the purchasing power they embody also rises, leading to an increase in aggregate expenditure. For example, in the 1990s there was a significant rise in the stock market that increased aggregate demand. And when the real value of household assets falls—

Size of the Existing Stock of Physical Capital Firms engage in planned investment spending to add to their stock of physical capital. Their incentive to spend depends in part on how much physical capital they already have: the more they have, the less they will feel a need to add more, other things equal. The same applies to other types of investment spending—

CHANGES IN WEALTH: A MOVEMENT ALONG VERSUS A SHIFT OF THE AGGREGATE DEMAND CURVE

In the last section we explained that one reason the AD curve is downward sloping is due to the wealth effect of a change in the aggregate price level: a higher aggregate price level reduces the purchasing power of households’ assets and leads to a fall in consumer spending, C. But in this section we’ve just explained that changes in wealth lead to a shift of the AD curve. Aren’t those two explanations contradictory? Which one is it—

Government Policies and Aggregate Demand

One of the key insights of macroeconomics is that the government can have a powerful influence on aggregate demand and that, in some circumstances, this influence can be used to improve economic performance.

The two main ways the government can influence the aggregate demand curve are through fiscal policy and monetary policy. We’ll briefly discuss their influence on aggregate demand, leaving a full-length discussion for upcoming chapters.

Fiscal Policy As we learned in Chapter 6, fiscal policy is the use of either government spending—government purchases of final goods and services and government transfers—or tax policy to stabilize the economy. In practice, governments often respond to recessions by increasing spending, cutting taxes, or both. They often respond to inflation by reducing spending or increasing taxes.

The effect of government purchases of final goods and services, G, on the aggregate demand curve is direct because government purchases are themselves a component of aggregate demand. So an increase in government purchases shifts the aggregate demand curve to the right and a decrease shifts it to the left. History’s most dramatic example of how increased government purchases affect aggregate demand was the effect of wartime government spending during World War II. Because of the war, real government purchases of goods and services surged 570%. This increase in purchases is usually credited with ending the Great Depression. Recent decades offer other examples of the effect of increased government spending. In the 1990s, Japan used large public works projects—such as government-financed construction of roads, bridges, and dams—in an effort to increase aggregate demand in the face of a slumping economy. Similarly, in 2009, to stimulate overall spending, federal and provincial governments in Canada began to spend more than $63 billion, mostly on infrastructure projects such as improving highways, bridges, public transportation, university and college buildings, and so on.

In contrast, changes in either tax rates or government transfers influence the economy indirectly through their effect on disposable income. A lower tax rate means that consumers get to keep more of what they earn, increasing their disposable income. An increase in government transfers also increases consumers’ disposable income. In either case, this increases consumer spending and shifts the aggregate demand curve to the right. A higher tax rate or a reduction in transfers reduces the amount of disposable income received by consumers. This reduces consumer spending and shifts the aggregate demand curve to the left.

Monetary Policy We opened this chapter by talking about the problems faced by the Bank of Canada, which controls monetary policy—the use of changes in the quantity of money or the interest rate to stabilize the economy. We’ve just discussed how a rise in the aggregate price level, by reducing the purchasing power of money holdings, causes a rise in the interest rate. That, in turn, reduces both investment spending and consumer spending.

But what happens if the quantity of money in the hands of households and firms changes? In modern economies, the quantity of money in circulation is largely determined by the decisions of a central bank created by the government. As we’ll learn in Chapter 14, the Bank of Canada, Canada’s central bank, is a special institution that is neither exactly part of the government nor exactly a private institution. When the central bank increases the quantity of money in circulation, households and firms have more money, which they are willing to lend out. The effect is to drive the interest rate down at any given aggregate price level, leading to higher investment spending and higher consumer spending. That is, increasing the quantity of money supplied shifts the aggregate demand curve to the right. Reducing the quantity of money supplied has the opposite effect: households and firms have less money holdings than before, leading them to borrow more and lend less. This raises the interest rate, reduces investment spending and consumer spending, and shifts the aggregate demand curve to the left.

MOVING ALONG THE AGGREGATE DEMAND CURVE, 1979-1982

When looking at data, it’s often hard to distinguish between changes in spending that represent movements along the aggregate demand curve and shifts of the aggregate demand curve. One telling exception, however, is what happened right after the oil crisis of 1979, which we mentioned in this chapter’s opening story. Faced with a sharp increase in the aggregate price level—the rate of consumer price inflation reached 12.9% in July of 1981— the Bank of Canada stuck to a policy of increasing the quantity of money slowly. The aggregate price level was rising more steeply, but the quantity of money circulating in the economy was growing slowly. The net result was that the purchasing power of the quantity of money in circulation fell.

This led to an increase in the demand for borrowing and a surge in interest rates. The prime rate, which is the interest rate banks charge their best customers, climbed to 22.75% in August 1981. High interest rates, in turn, caused both consumer spending and investment spending to fall: in 1982 purchases of durable consumer goods like cars fell by about 12% and real investment spending fell by 27.5%.

In other words, in 1979-1982 the economy responded just as we’d expect if it were moving upward along the aggregate demand curve from right to left: due to the wealth effect and the interest rate effect of a change in the aggregate price level, the quantity of aggregate output demanded fell as the aggregate price level rose. This does not explain, of course, why the aggregate price level rose. But as we’ll see in the section “The AD-AS Model,” the answer to that question lies in the behaviour of the short-run aggregate supply curve.

Quick Review

The aggregate demand curve is downward sloping because of the wealth effect of a change in the aggregate price level and the interest rate effect of a change in the aggregate price level.

The aggregate demand curve shows how income–expenditure equilibrium GDP changes when the aggregate price level changes.

Changes in consumer spending caused by changes in wealth and expectations about the future shift the aggregate demand curve. Changes in investment spending caused by changes in expectations and by the size of the existing stock of physical capital also shift the aggregate demand curve.

Fiscal policy affects aggregate demand directly through government purchases and indirectly through changes in taxes or government transfers. Monetary policy affects aggregate demand indirectly through changes in the interest rate.

Check Your Understanding 12-1

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 12-1

Determine the effect on aggregate demand of each of the following events. Explain whether it represents a movement along the aggregate demand curve (up or down) or a shift of the curve (leftward or rightward).

A rise in the interest rate caused by a change in monetary policy

A fall in the real value of money in the economy due to a higher aggregate price level

News of a worse-than-expected job market next year

A fall in tax rates

A rise in the real value of assets in the economy due to a lower aggregate price level

A rise in the real value of assets in the economy due to a surge in real estate values

This is a shift of the aggregate demand curve. A decrease in the quantity of money raises the interest rate, since people now want to borrow more and lend less. A higher interest rate reduces investment and consumer spending at any given aggregate price level. So the aggregate demand curve shifts to the left.

This is a movement up along the aggregate demand curve. As the aggregate price level rises, the real value of money holdings falls. This is the interest rate effect of a change in the aggregate price level: as the value of money falls, people want to hold more money. They do so by borrowing more and lending less. This leads to a rise in the interest rate and a reduction in consumer and investment spending. So it is a movement along the aggregate demand curve.

This is a shift of the aggregate demand curve. Expectations of a poor job market, and so lower average disposable incomes, will reduce people’s consumer spending today at any given aggregate price level. So the aggregate demand curve shifts to the left.

This is a shift of the aggregate demand curve. A fall in tax rates raises people’s disposable income. At any given aggregate price level, consumer spending is now higher. So the aggregate demand curve shifts to the right.

This is a movement down along the aggregate demand curve. As the aggregate price level falls, the real value of assets rises. This is the wealth effect of a change in the aggregate price level: as the value of assets rises, people will increase their consumption plans. This leads to higher consumer spending. So it is a movement along the aggregate demand curve.

This is a shift of the aggregate demand curve. A rise in the real value of assets in the economy due to a surge in real estate values raises consumer spending at any given aggregate price level. So the aggregate demand curve shifts to the right.