12.4 Macroeconomic Policy

We’ve just seen that the economy is self-

This belief is the background to one of the most famous quotations in economics: John Maynard Keynes’s declaration, “In the long run we are all dead.” We explain the context in which he made this remark in the accompanying For Inquiring Minds.

KEYNES AND THE LONG RUN

The British economist Sir John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946), probably more than any other single economist, created the modern field of macroeconomics. We’ll look at his role, and the controversies that still swirl around some aspects of his thought, in a later chapter on macroeconomic events and ideas. But for now let’s just look at his most famous quote.

In 1923 Keynes published A Tract on Monetary Reform, a small book on the economic problems of Europe after World War I. In it he decried the tendency of many of his colleagues to focus on how things work out in the long run—

This long run is a misleading guide to current affairs. In the long run we are all dead. Economists set themselves too easy, too useless a task if in tempestuous seasons they can only tell us that when the storm is long past the sea is flat again.

Stabilization policy is the use of government policy to reduce the severity and duration of recessions and rein in excessively strong expansions.

Economists usually interpret Keynes as having recommended that governments and central banks not wait for the economy to correct itself. Instead, it is argued by many economists, but not all, that the governments and central banks should use monetary and fiscal policy to help get the economy back to potential output more quickly in the aftermath of a shift of the aggregate demand curve. This is the rationale for an active stabilization policy, which is the use of government policy to reduce the severity and duration of recessions and rein in excessively strong expansions.

Can stabilization policy improve the economy’s performance? If we re-

Policy in the Face of Demand Shocks

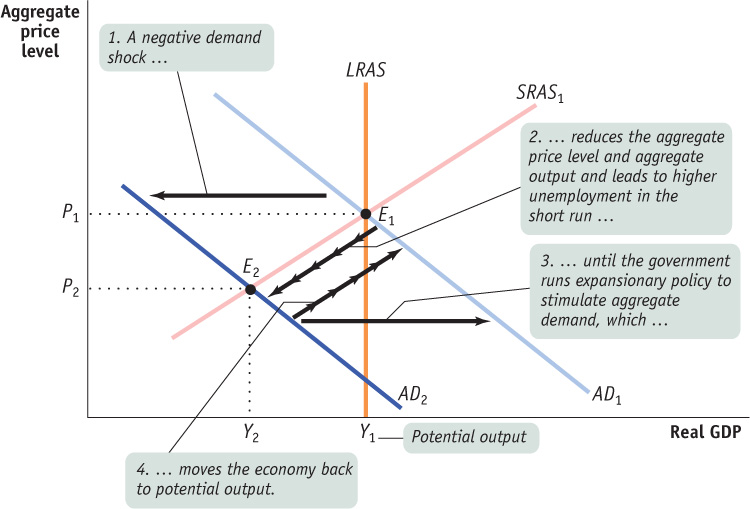

Imagine that the economy experiences a negative demand shock, like the one shown in Figure 12-21. As we’ve discussed in this chapter, monetary and fiscal policy shift the aggregate demand curve. If policy-

Why might a policy that short-

Does this mean that governments and the central bank should always act to offset declines in aggregate demand? Not necessarily. As we’ll see in later chapters, some policy measures to increase aggregate demand, especially those that increase budget deficits, may have long-

Should policy-

But how should macroeconomic policy respond to supply shocks?

Responding to Supply Shocks

We’ve now come full circle to the story that began this chapter. We can now explain why the governor of the Bank of Canada dreads inflation.

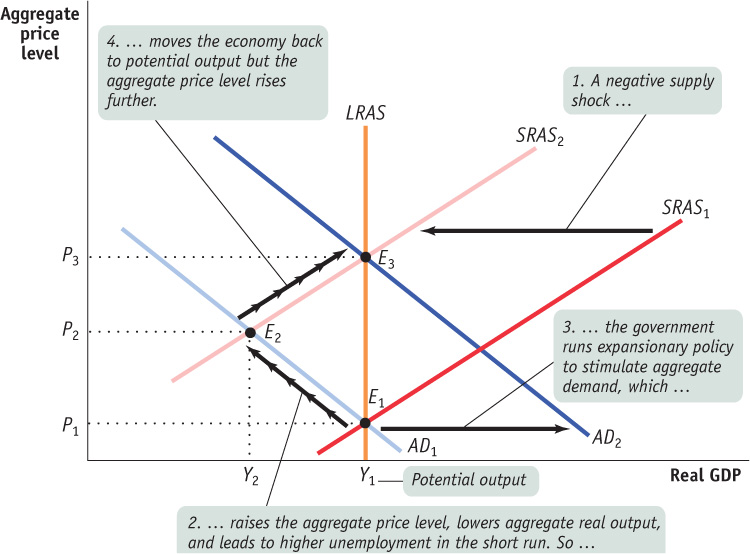

Back in panel (a) of Figure 12-14 we showed the effects of a negative supply shock: in the short run such a shock leads to lower aggregate output but a higher aggregate price level. As we’ve noted, policy-makers can respond to a negative demand shock by using monetary and fiscal policy to return aggregate demand to its original level. But what can or should they do about a negative supply shock?

In contrast to the aggregate demand curve, there are no easy policies that shift the short-run aggregate supply curve. That is, there is no government policy that can easily affect producers’ profitability and so compensate for shifts of the short-run aggregate supply curve. So the policy response to a negative supply shock cannot aim to simply push the curve that shifted back to its original position.

And if you consider using monetary or fiscal policy to shift the aggregate demand curve in response to a supply shock, the right response isn’t obvious. Two bad things are happening simultaneously: a fall in aggregate output, leading to a rise in unemployment, and a rise in the aggregate price level. Any policy that shifts the aggregate demand curve helps one problem only by making the other worse. As shown in Figure 12-22, if the government acts to increase aggregate demand and limit the rise in unemployment, it reduces the decline in output but causes even more inflation. If it acts to reduce aggregate demand, it curbs inflation but causes a further rise in unemployment.

It’s a trade-off with no good answer. In the end, Canada and other economically advanced nations suffering from the supply shocks of the 1970s eventually chose to stabilize prices even at the cost of higher unemployment. But being an economic policy-maker in the 1970s, or in early 2008, meant facing even harder choices than usual. When Canada experienced adverse supply shocks in the 1970s and the inflation rate hit double digits, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau introduced the Anti-Inflation Act in 1975. The aim of this act was to slow the rate of increase in wages and prices. The government hoped that this step would shift the short-run aggregate supply curve to the right, and partially offset the adverse effects of the initial leftward shift in SRAS. Unfortunately, this attempt was unsuccessful, as the Canadian economy still suffered from high inflation and high unemployment. Eventually, the wage and price control policy was repealed in 1979.

IS STABILIZATION POLICY STABILIZING?

We’ve described the theoretical rationale for stabilization policy as a way of responding to demand shocks. But does stabilization policy actually stabilize the economy? One way we might try to answer this question is to look at the long-term historical record. Before World War II, the Canadian government didn’t really have a stabilization policy—largely because macroeconomics as we know it didn’t exist—and there was no consensus about what to do. Since World War II, and especially since 1960, active stabilization policy has become standard practice.

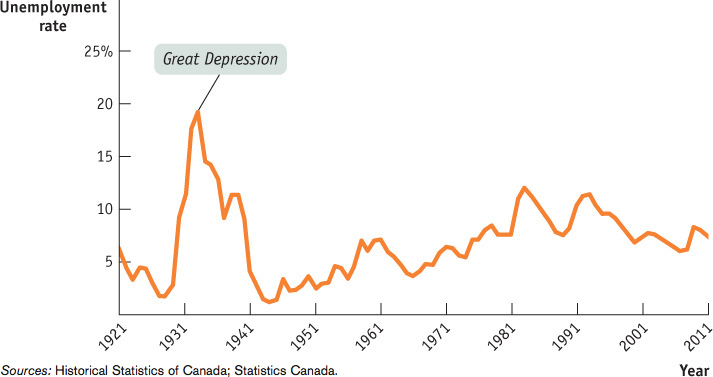

So here’s the question: has the economy actually become more stable since the government began trying to stabilize it? To answer this question, we need to look at the data. Figure 12-23 shows the unemployment rate between 1921 and 2011. Even ignoring the huge spike in unemployment during the Great Depression, unemployment seems to have varied a lot. Since 1960 Canada experienced three recessions—in the early 1980s, in the early 1990s, and again in 2008-2009, and in all these recessions the unemployment rate rose. From this observation one might conclude that stabilization policy fails to reduce fluctuations in unemployment. Is it true? The answer is no, because of the causes of the recessions.

Each of the three recessions we have had since the 1980s had a different cause. The recession in early 1980s was a classic example of an adverse supply-side shock: the economy was pushed into a recession by a significant hike in oil prices. This hike shifted the short-run aggregate supply curve leftward, causing a higher price level and higher unemployment rate. Unfortunately, policy-makers have to choose between fighting the high inflation rate or high unemployment—no stabilization policy deals with both hazards simultaneously. As Figure 12-23 shows, the unemployment rate again rose above double digits in the early 1990s. This time, the recession was caused by a change in the Bank of Canada’s monetary policy. The Bank decided that the inflation rate was too high, and it was necessary to pursue a disinflationary policy. This “contractionary” monetary policy lowered aggregate demand and pushed the economy into a recession. This is a good example of how the Bank of Canada’s two goals—low unemployment and low, stable prices—can be in conflict with each other. The Bank chose to lower the inflation rate and paid the price of higher unemployment. The 2008-2009 recession was caused mainly by a negative demand-side shock from the U.S., with the bursting of their housing price bubble. Both the federal government and the Bank of Canada reacted to this shock aggressively by using various measures to offset the fall in aggregate demand. The federal government undertook expansionary fiscal policy, by increasing spending on infrastructure, targeting tax cuts, and so on. The Bank of Canada enacted an expansionary monetary policy, slashing the bank interest rate to increase the money supply. Although the unemployment rate did increase on this occasion, it did not increase as much as in the previous two recessions. This suggests that stabilization policy can indeed be stabilizing.

Quick Review

Stabilization policy is the use of fiscal or monetary policy to offset demand shocks. There can be drawbacks, however. Such policies may lead to a long-term rise in the budget deficit and lower long-run growth because of crowding out. And, due to incorrect predictions, a misguided policy can increase economic instability.

Negative supply shocks pose a policy dilemma because fighting the slump in aggregate output worsens inflation and fighting inflation worsens the slump.

Check Your Understanding 12-4

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 12-4

Suppose someone says, “Using monetary or fiscal policy to pump up the economy is counterproductive—you get a brief high, but then you have the pain of inflation.”

Explain what this means in terms of the AD-AS model.

Is this a valid argument against stabilization policy? Why or why not?

An economy is overstimulated when an inflationary gap is present. This will arise if an expansionary monetary or fiscal policy is implemented when the economy is currently in long-run macroeconomic equilibrium. This shifts the aggregate demand curve to the right, in the short run raising the aggregate price level and aggregate output and creating an inflationary gap. Eventually nominal wages will rise and shift the short-run aggregate supply curve to the left, and aggregate output will fall back to potential output while the aggregate price level will be higher. This is the scenario envisaged by the speaker.

No, this is not a valid argument. When the economy is not currently in long-run macroeconomic equilibrium, an expansionary monetary or fiscal policy does not lead to the outcome described above. Suppose a negative demand shock has shifted the aggregate demand curve to the left, resulting in a recessionary gap. An expansionary monetary or fiscal policy can shift the aggregate demand curve back to its original position in long-run macroeconomic equilibrium. In this way, the short-run fall in aggregate output and deflation caused by the original negative demand shock can be avoided. So, if used in response to demand shocks, fiscal or monetary policy is an effective policy tool.

In 2008, in the aftermath of the collapse of the U.S. housing bubble and a sharp rise in the price of commodities, particularly oil, there was much internal disagreement within the Bank of Canada about how to properly respond. Some analysts advocated lowering interest rates, but others disagreed, saying that this would set off a rise in inflation. Explain the reasoning behind each one of these views in terms of the AD-AS model.

Those within the BOC who advocated lowering interest rates were focused on boosting aggregate demand in order to counteract the negative demand shock caused by the collapse of the U.S. housing bubble. Lowering interest rates will result in a rightward shift of the aggregate demand curve, increasing aggregate output but raising the aggregate price level. Those within the BOC who advocated holding interest rates steady were focused on the fact that fighting the slump in aggregate demand in the face of a negative supply shock could result in a rise in inflation. Holding interest rates steady relies on the ability of the economy to self-correct in the long run, with the aggregate price level and aggregate output only gradually returning to their levels before the negative supply shock.

Flying the Ups and Downs of the Business Cycle

The airline industry is notoriously “cyclical.” That is, instead of making profits all through the business cycle, it tends to plunge into losses during recessions, only regaining profitability sometime after recovery begins. Mainly this is because airlines have large fixed costs that remain high, even if ticket sales slump. The cost of operating a flight from one city to another is pretty much the same whether the flight is fully booked or two-thirds empty, so when business slumps for whatever reason, even highly profitable routes quickly become money-losers. It’s true that airlines can to some extent adapt to a decline in business by switching to smaller planes, consolidating flights, and so on, but this process takes time and still tends to leave costs per passenger higher than before.

But some recessions are worse for airlines than for other businesses, because Operating costs rise even as demand falls. This was very much the case in 2008. Hit by the global recession and rising fuel prices, Air Canada, our largest airline, suffered a net loss of $132 million (compared to a net income of $273 million a year earlier and net income of $122 million in the previous quarter).

Business travel had started to slacken, but at that point leisure travel was still holding up. So why was Air Canada in so much trouble? Mainly, Air Canada was hurt by the cost of fuel, which soared in late 2007 and 2008. Fuel prices did fall in late 2008, but by that time Air Canada was suffering from a sharp drop in ticket sales. Air Canada finally returned to profitability in 2010, only to see fuel prices take off once again in early 2011, returning it and other airlines to a difficult financial position.

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

How did Air Canada’s problems in early 2008 relate to our analysis of the causes of recessions?

How did Air Canada’s problems in early 2008 relate to our analysis of the causes of recessions?

Mark Carney had to choose between fighting two economic evils in 2008. How would his choice affect Air Canada compared with, say, a company producing a service without expensive raw material inputs, like a publisher?

Mark Carney had to choose between fighting two economic evils in 2008. How would his choice affect Air Canada compared with, say, a company producing a service without expensive raw material inputs, like a publisher?

In early 2008, business travel was beginning to slacken, but leisure travel was still holding up. Given the situation the overall economy was in, what would you expect to happen to leisure travel as the economy moved further into recession?

In early 2008, business travel was beginning to slacken, but leisure travel was still holding up. Given the situation the overall economy was in, what would you expect to happen to leisure travel as the economy moved further into recession?