Fiscal Policy

13

What fiscal policy is and why it is an important tool in managing economic fluctuations

Which policies constitute an expansionary fiscal policy and which constitute a contractionary fiscal policy

Why fiscal policy has a multiplier effect and how this effect is influenced by automatic stabilizers

Why governments calculate the cyclically adjusted budget balance

Why a large public debt may be a cause for concern

Why implicit liabilities of the government are also a cause for concern

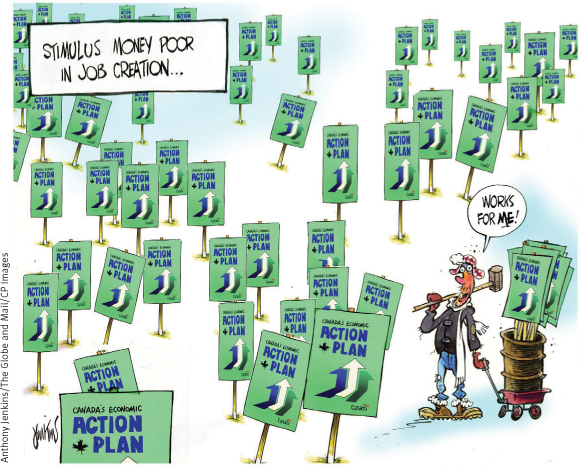

TO STIMULATE OR NOT TO STIMULATE?

ON JANUARY 27, 2009, PRIME Minister Harper’s government introduced its 2009 Budget Implementation Act. Often called Budget 2009: Canada’s Economic Action Plan (EAP), this was a $62 billion package of spending, transfers, and tax cuts intended to help the struggling Canadian economy to reverse a severe recession that began in late 2008. The minister of finance, Jim Flaherty, stated at the time, “It builds on our position of strength. It provides temporary and effective economic stimulus to help Canadian families and businesses deal with short-

Others weren’t so sure that would be the case. They argued that at a time when Canadian families were suffering, the government should cut spending, not increase it. “Canadians will inevitably see higher taxes as a result of the federal government’s plan to stimulate the economy with deficit spending,” said financial commentator Evelyn Jacks. “Already, the federal and provincial taxes every Canadian pays on income and capital are by far the largest destroyer of wealth over a lifetime. These deficits won’t help,” Jacks said. Some economic analysts were concerned that the so-

Others had the opposite complaint—

The passage of time did not resolve these disputes. On one hand, the bill did not jump-

Whatever the verdict—