13.1 Fiscal Policy: The Basics

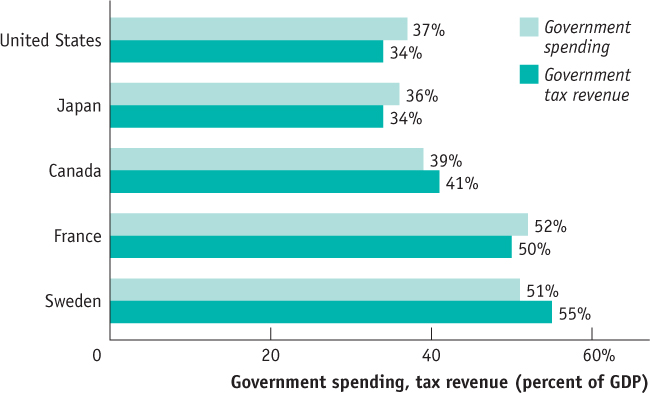

Let’s begin with the obvious: modern governments in economically advanced countries spend a great deal of money and collect a lot in taxes. Figure 13-1 shows government spending and tax revenue as percentages of GDP for a selection of high-

Source: OECD.

To analyze these effects, we begin by showing how taxes and government spending affect the economy’s flow of income. Then we can see how changes in spending and tax policy affect aggregate demand.

Taxes, Purchases of Goods and Services, Government Transfers, and Borrowing

In Figure 7-1 we showed the circular flow of income and spending in the economy as a whole. One of the sectors represented in that figure was the government. Funds flow into the government in the form of taxes and government borrowing; funds flow out in the form of government purchases of goods and services and government transfers to households.

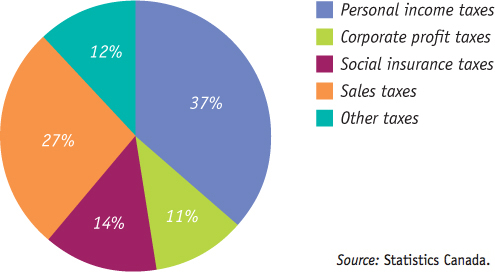

What kinds of taxes do Canadians pay, and where does the money go? Figure 13-2 shows the composition of Canadian tax revenue in 2007. Taxes, of course, are required payments to the government. In Canada, taxes are collected at the national level by the federal government; at the provincial or territorial level by each provincial or territorial government; and at local levels by counties, cities, and towns. At the federal level, the taxes that generate the greatest revenue are income taxes on both personal income and corporate profits as well as social insurance taxes, which we’ll explain shortly. At the provincial and local levels, the picture is more complex: these governments rely on a mix of sales taxes, property taxes, income taxes, and fees of various kinds. Overall, taxes on personal income and corporate profits accounted for 48% of total government revenue in 2007; social insurance taxes accounted for 14%; and a variety of other taxes, collected mainly at the provincial and local levels, accounted for the rest.

Source: Statistics Canada.

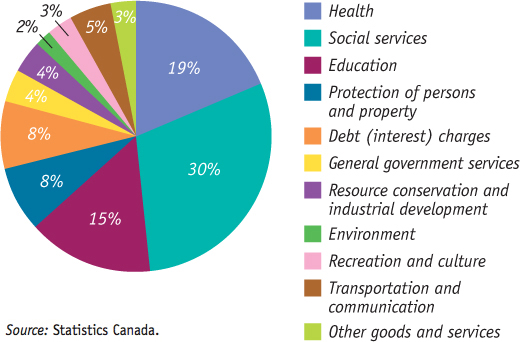

Figure 13-3 shows the composition of total Canadian government spending in 2007, which, after the payment of interest on government debt, takes two broad forms.1 One form is purchases of goods and services by government. These direct purchases are counted as part of government purchases of goods and services (the G term) in the expenditure approach to measuring GDP (as discussed in Chapter 7). These purchases include everything from diagnostic equipment for hospitals to the salaries of public school teachers (who are treated in the national accounts as providers of a service—

Source: Statistics Canada.

The other form of government spending is government transfers, which are payments by the government to households for which no good or service is provided in return. These transfers might be targeted to certain types of activities or spending by households, such as education or health care. Since transfers do not represent direct spending on final output, they are not counted in the G term in the expenditure approach. In fact, should the transfer help households finance some of their consumption, this will be captured in the private sector consumption, term C, in the expenditure approach.2 Government transfers represent a huge proportion of Canada’s budget, as well as those of the United States and Europe. In Canada, most transfer payments cover two broad areas:

Public pension plans, which provide guaranteed income to older Canadians, disabled Canadians, and the surviving spouses and dependent children of deceased or retired beneficiaries

Other social assistance payments, which help individuals and families to maintain an acceptable level of earnings

Social insurance programs are government programs intended to protect families against economic hardship.

The term social insurance describes government programs intended to protect families against economic hardship. These include payments from public pension plans such as the Canada/Quebec Pension Plan (CPP/QPP), Old Age Security (OAS), Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS), and so on. Other social assistance payments include general welfare and family allowance payments, as well as smaller programs such as veterans’ benefits, motor vehicle accident compensation payments, legal aid, and daycare subsidies. In Canada, social insurance programs are paid for largely with special, dedicated taxes on wages—

But how do tax policy and government spending affect the economy? The answer is that taxation and government spending have a strong effect on total aggregate expenditure in the economy.

The Government Budget and Total Spending

Let’s recall the basic equation of national income accounting:

The left-

The government directly controls one of the variables on the right-

To see why the budget affects consumer spending, recall that disposable income, the total income households have available to spend, is equal to the total income they receive from wages, dividends, interest, and rent, minus taxes, plus government transfers. So either an increase in taxes or a reduction in government transfers reduces disposable income. And a fall in disposable income, other things equal, leads to a fall in consumer spending. Conversely, either a decrease in taxes or an increase in government transfers increases disposable income. And a rise in disposable income, other things equal, leads to a rise in consumer spending.

The government’s ability to affect investment spending is a more complex story, which we won’t discuss in detail. The important point is that the government taxes profits and capital goods spending, and changes in the rules that determine how much a business owes can increase or reduce the incentive to spend on investment goods.

Because the government itself is one source of spending in the economy, and because taxes and transfers can affect spending by consumers and firms, the government can use changes in taxes or government spending to shift the aggregate demand curve. And as we saw in Chapter 12, there are sometimes good reasons to shift the aggregate demand curve. In early 2009, as this chapter’s opening story explained, the Harper government believed it was crucial that the Canadian government act to increase aggregate demand—

Expansionary and Contractionary Fiscal Policy

Why would the government want to shift the aggregate demand curve? Because it wants to close either a recessionary gap, created when aggregate output falls below potential output, or an inflationary gap, created when aggregate output exceeds potential output. Such gaps, created when output is not at the economy’s full employment level, are harmful to the welfare of households and firms. The government has the “power” to influence AD, by shifting the AD curve, so as to reduce the gap, thereby making households and firms better off. Governments have found that interventions to influence AS in order to close the gap are not so simple.

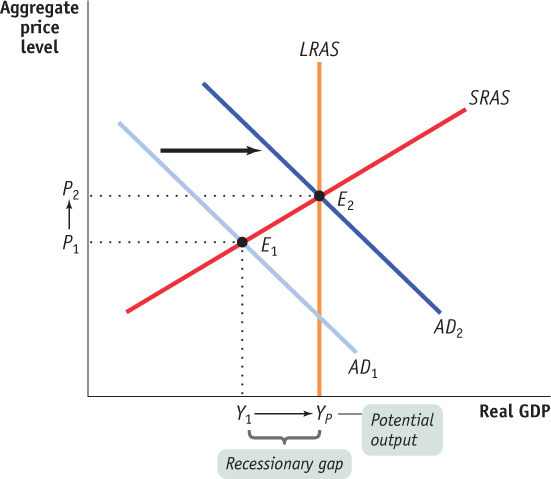

Figure 13-4 shows the case of an economy facing a recessionary gap. SRAS is the short-

Expansionary fiscal policy is fiscal policy that increases aggregate demand.

Fiscal policy that increases aggregate demand, called expansionary fiscal policy, normally takes one of three forms, or some combination of them:

An increase in government purchases of goods and services

A cut in taxes

An increase in government transfers

The 2009 Economic Action Plan was a combination of all three: a direct increase in federal spending and aid to provincial, territorial, and municipal governments to help them to finance “ready-

Contractionary fiscal policy is fiscal policy that reduces aggregate demand.

Figure 13-5 shows the opposite case—

A reduction in government purchases of goods and services

An increase in taxes

A reduction in government transfers

A classic example of contractionary fiscal policy occurred in 1995, when the federal government grew worried about Canada’s large budget deficit and growing debt burden as a percentage of the economy. Things were so bad the Wall Street Journal called Canada an honorary member of the third world. As a percent of the economy, the 1995 budget introduced the largest cuts to Canadian federal spending since the end of World War II. This federal budget combined large direct spending cuts, significant reductions in transfer payments to individuals and provinces, along with small tax increases.

Can Expansionary Fiscal Policy Actually Work?

In practice, the use of fiscal policy—

Broadly speaking, there are three arguments against the use of expansionary fiscal policy:

Government spending always crowds out private spending

Government borrowing always crowds out private investment spending

Government budget deficits lead to reduced private spending

The first of these claims is wrong in principle, but it has nonetheless played a prominent role in public debates. The second is valid under some, but not all, circumstances. The third argument, although it raises some important issues, isn’t a good reason to believe that expansionary fiscal policy doesn’t work.

Claim 1: “Government Spending Always Crowds Out Private Spending” Some claim that expansionary fiscal policy can never raise aggregate expenditure and therefore can never raise aggregate income, with reasons that go something like this: “Every dollar that the government spends is a dollar taken away from the private sector. So any rise in government spending must be offset by an equal fall in private spending.” In other words, every dollar spent by the government crowds out, or displaces, a dollar of private spending. So what’s wrong with this view? The answer is that the statement is wrong because it assumes that resources in the economy are always fully employed and, as a result, the aggregate income earned in the economy is always a fixed sum—

Claim 2: “Government Borrowing Always Crowds Out Private Investment Spending” In Chapter 10, we discussed the possibility that government borrowing uses funds that would have otherwise been used for private investment spending—

The answer is “it depends.” Specifically, it depends upon whether the economy is depressed or not. If the economy is not depressed, then increased government borrowing, by increasing the demand for loanable funds, can raise interest rates and crowd out private investment spending. However, what if the economy is depressed? In that case, crowding out is much less likely. When the economy is at far less than full employment, a fiscal expansion will lead to higher incomes, which in turn leads to increased savings at any given interest rate. This larger pool of savings allows the government to borrow without driving up interest rates. Canada’s Economic Action Plan of 2009 was a case in point: despite high levels of government borrowing, Canadian interest rates stayed near historic lows. This, though, was partly owing to the Bank of Canada’s expansionary monetary policy.

Claim 3: “Government Budget Deficits Lead to Reduced Private Spending” Other things equal, expansionary fiscal policy leads to a larger budget deficit and greater government debt. And higher debt will eventually require the government to raise taxes to pay it off. So, according to the third argument against expansionary fiscal policy, consumers, anticipating that they must pay higher taxes in the future to pay off today’s government debt, will cut their spending today in order to save more now—

In reality, however, it’s doubtful that consumers behave with such foresight and budgeting discipline. Most people, when provided with extra cash (generated by the fiscal expansion), will spend at least some of it. So even fiscal policy that takes the form of temporary tax cuts or transfers of cash to consumers probably does have an expansionary effect.

Moreover, it’s possible to show that even with Ricardian equivalence, a temporary rise in government spending that involves direct purchases of goods and services—

In sum, then, the extent to which we should expect expansionary fiscal policy to work depends upon the circumstances. When the economy has a recessionary gap—

A Cautionary Note: Lags in Fiscal Policy

Looking back at Figures 13-4 and 13-5, it may seem obvious that the government should actively use fiscal policy—always adopting an expansionary fiscal policy when the economy faces a recessionary gap and always adopting a contractionary fiscal policy when the economy faces an inflationary gap. But many economists caution against an extremely active stabilization policy, arguing that a government that tries too hard to stabilize the economy—through either fiscal policy or monetary policy—can end up making the economy less stable.

We’ll leave discussion of the warnings associated with monetary policy to Chapter 19. In the case of fiscal policy, one key reason for caution is that there are important time lags between when the policy is decided upon and when it is implemented. To understand the nature of these lags, think about what has to happen before the government increases spending to fight a recessionary gap. First, the government has to realize that the recessionary gap exists: economic data take time to collect and analyze, and recessions are often recognized only months after they have begun. Second, the government has to develop a spending plan, which can itself take months, particularly if politicians take time debating how the money should be spent and passing legislation. Finally, it takes time to spend money. For example, a road construction project begins with activities such as surveying that don’t involve spending large sums. It may be quite some time before the big spending begins.

Because of these lags, an attempt to increase spending to fight a recessionary gap may take so long to get going that the economy has already recovered on its own. In fact, the recessionary gap may have turned into an inflationary gap by the time the fiscal policy takes effect. In that case, the fiscal policy will make things worse instead of better.

This doesn’t mean that fiscal policy should never be actively used. In early 2009 there was good reason to believe that the slump facing the Canadian economy would be both deep and long and that a fiscal stimulus designed to arrive over the next year or two would almost surely push aggregate demand in the right direction. In fact, as we’ll see later in this chapter, the 2009 stimulus arguably faded out too soon, leaving the economy still depressed. But the problem of lags makes the actual use of both fiscal and monetary policy harder than you might think from a simple analysis like the one we have just given.

WHAT WAS IN CANADA’S 2009 ECONOMIC ACTION PLAN?

As we’ve just learned, fiscal stimulus can take three forms: increased government purchases of goods and services, increased transfer payments, and tax cuts. So what form did the government’s Economic Action Plan take? Well, it’s a bit complicated.

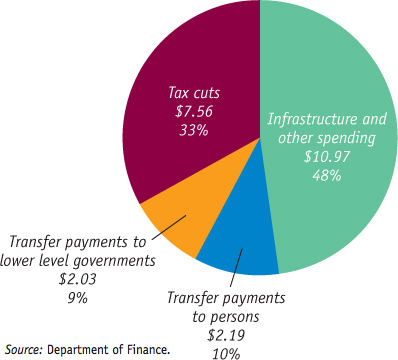

Figure 13-6 shows the composition of the 2009–2010 budget impact of the Action Plan, a measure that adds up the dollar value of tax cuts, transfer payments, and government spending. Here, the numbers are broken down into four categories, not three. “Infrastructure and other spending” means spending on roads, bridges, and schools as well as “nontraditional” infrastructure like research and development, all of which fall under government purchases of goods and services. “Tax cuts” are self-explanatory. “Transfer payments to persons” mostly took the form of expanded benefits for the unemployed and additional spending on training programs. But a fourth category, “transfers to lower level governments,” accounted for almost a tenth of the funds. Why this fourth category?

Source: Department of Finance.

It’s because Canada has multiple levels of government. The Canadian authors of this book live in the city of Toronto, which has its own budget. But Toronto is part of the province of Ontario, which has its own budget. And Ontario is part of Canada, which of course has its budget. One effect of the recession was a sharp drop in revenues at the provincial/territorial and local levels, which in turn forced these lower levels of government to consider significant spending cuts. Federal aid—those transfers to provincial and local governments—was intended to mitigate these spending cuts.

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of the Action Plan was how little direct federal spending on goods and services was involved. The great bulk of the program involved giving money to other people, one way or another, in the hope that they would spend it.

Quick Review

The main channels of fiscal policy are taxes and government spending. Government spending takes the form of purchases of goods and services as well as transfers.

In Canada, most government transfers are accounted for by social insurance programs designed to alleviate economic hardship—mainly public pensions (e.g., CPP/QPP, OAS, and GIS), and social assistance benefits, such as general welfare and family allowance programs.

The government controls G directly and influences C and I through taxes and transfers.

Expansionary fiscal policy is implemented by an increase in government spending, a cut in taxes, or an increase in government transfers. Contractionary fiscal policy is implemented by a reduction in government spending, an increase in taxes, or a reduction in government transfers.

Arguments against the effectiveness of expansionary fiscal policy based upon crowding out are valid only when the economy is at full employment. The argument that expansionary fiscal policy won’t work because of Ricardian equivalence—that consumers will cut back spending today to offset expected future tax increases—appears to be untrue in practice. What is clearly true is that time lags can reduce the effectiveness of fiscal policy, and potentially render it counterproductive.

Check Your Understanding 13-1

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 13-1

In each of the following cases, determine whether the policy is an expansionary or contractionary fiscal policy.

Several armed forces bases around the country, which together employ tens of thousands of people, are closed.

The number of weeks an unemployed person is eligible for employment insurance benefits is increased.

The federal tax on gasoline is increased.

This is a contractionary fiscal policy because it is a reduction in government purchases of goods and services.

This is an expansionary fiscal policy because it is an increase in government transfers that will increase disposable income.

This is a contractionary fiscal policy because it is an increase in taxes that will reduce disposable income.

Explain why federal disaster relief, which quickly disburses funds to victims of natural disasters such as hurricanes, floods, and large-scale crop failures, will stabilize the economy more effectively after a disaster than relief that must be legislated.

Federal disaster relief that is quickly disbursed is more effective than legislated aid because there is very little time lag between the time of the disaster and the time it is received by victims. So it will stabilize the economy after a disaster. In contrast, legislated aid is likely to entail a time lag in its disbursement, potentially destabilizing the economy.

Is the following statement true or false? Explain. “When the government expands, the private sector shrinks; when the government shrinks, the private sector expands.”

This statement implies that expansionary fiscal policy will result in crowding out of the private sector, and that the opposite, contractionary fiscal policy, will lead the private sector to grow. Whether this statement is true or not depends upon whether the economy is at full employment; it is only then that we should expect expansionary fiscal policy to lead to crowding out. If, instead, the economy has a recessionary gap, then we should expect instead that the private sector grows along with the fiscal expansion, and contracts along with a fiscal contraction.