14.1 The Meaning of Money

In everyday conversation, people often use the word money to mean “wealth.” If you ask, “How much money does Bill Gates have?” the answer will be something like, “Oh, $50 billion or so, but who’s counting?” That is, the number will include the value of the stocks, bonds, real estate, and other assets he owns.

But the economist’s definition of money doesn’t include all forms of wealth. The dollar bills in your wallet are money; other forms of wealth—

What Is Money?

Money is any asset that can easily be used to purchase goods and services.

Money is defined in terms of what it does: money is any asset that can easily be used to purchase goods and services. In Chapter 10 we defined an asset as liquid if it can easily be converted into cash. Money consists of cash itself, which is liquid by definition, as well as other assets that are highly liquid.

You can see the distinction between money and other assets by asking yourself how you pay for groceries. The person at the cash register will accept dollar bills in return for milk and frozen pizza—

Currency in circulation is cash held by the public.

Of course, many stores allow you to write a cheque on your bank account in payment for goods (or to pay with a debit card that is linked to your bank account). Does that make your bank account money, even if you haven’t converted it into cash? Yes. Currency in circulation—actual cash in the hands of the public—

Chequeable deposits (or demand deposits) are bank accounts on which people can write cheques.

The money supply is the total value of financial assets in the economy that are considered money.

Are currency and chequeable bank deposits the only assets that are considered to be money? It depends. As we’ll see later, there are several widely used definitions of the money supply, the total value of financial assets in the economy that are considered money. The narrower definitions consider only the most liquid assets to be money: currency in circulation and chequeable deposits (also called demand deposits). The broader definitions include these two categories plus other assets that are almost chequeable, such as saving account deposits at chartered banks, trust and mortgage loan companies, credit unions, and caisses populaires. However, all of the definitions distinguish between assets that can easily be used to buy goods and services and those that can’t.

Money plays a crucial role in generating gains from trade because it makes indirect exchange possible. Think of what happens when a cardiac surgeon buys a new refrigerator. The surgeon has valuable services to offer—

This is known as the problem of finding a “double coincidence of wants”: in a barter system, two parties can trade only when each wants what the other has to offer. Money solves this problem: individuals can trade what they have to offer for money and trade money for what they want.

Because the ability to make transactions with money rather than relying on bartering makes it easier to achieve gains from trade, the existence of money increases welfare, even though money does not directly produce anything. In other words, it saves time and resources spent on finding another suitable party that is willing to trade with us. As Adam Smith put it, money “may very properly be compared to a highway, which, while it circulates and carries to market all the grass and corn of the country, produces itself not a single pile of either.”

Let’s take a closer look at the roles money plays in the economy.

Roles of Money

Money plays three main roles in any modern economy: it is a medium of exchange, a store of value, and a unit of account.

A medium of exchange is an asset that individuals acquire for the purpose of trading goods and services rather than for their own consumption.

1. Medium of Exchange Our cardiac surgeon/refrigerator example illustrates the role of money as a medium of exchange—an asset that individuals use to trade for goods and services rather than for consumption. People can’t eat dollar bills; rather, they use dollar bills to trade for edible goods and their accompanying services.

In normal times, the official money of a given country—

THE BIG MONEYS

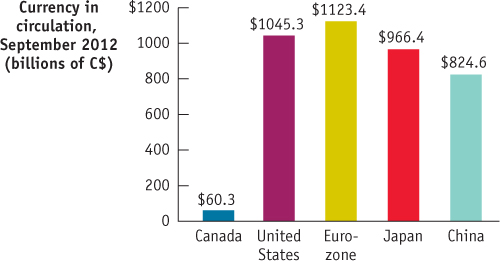

It is not just Americans who consider the U.S. dollar the world’s leading currency. Most other countries, including Canada, would agree—

Sources: Bank of Canada; Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; European Central Bank; Bank of Japan; the People’s Bank of China.

A store of value is a means of holding purchasing power over time.

2. Store of Value In order to act as a medium of exchange, money must also be a store of value—a means of holding purchasing power over time. To see why this is necessary, imagine trying to operate an economy in which ice cream cones were the medium of exchange. Such an economy would quickly suffer from, well, monetary meltdown: your medium of exchange would often turn into a sticky puddle before you could use it to buy something else. (As we’ll see in Chapter 16, one of the problems caused by high inflation is that, in effect, it causes the value of money to “melt.”) Of course, money is by no means the only store of value. Any asset that holds its purchasing power over time is a store of value. So the store-

A unit of account is a measure used to set prices and make economic calculations.

3. Unit of Account Finally, money normally serves as the unit of account—the commonly accepted measure individuals use to set prices and make economic calculations. To understand the importance of this role, consider a historical fact: during the Middle Ages, peasants typically were required to provide landowners with goods and labour rather than money. A peasant might, for example, be required to work on the lord’s land one day a week and hand over one-

Today, rents, like other prices, are almost always specified in money terms. That makes things much clearer: imagine how hard it would be to decide which apartment to rent if modern landlords followed medieval practice. Suppose, for example, that Mr. Smith says he’ll let you have a place if you clean his house twice a week and bring him a kilogram of steak every day, whereas Ms. Jones wants you to clean her house just once a week but wants four kilograms of chicken every day. Who’s offering the better deal? It’s hard to say. If, instead, Smith wants $600 a month and Jones wants $700, the comparison is easy. In other words, without a commonly accepted measure, the terms of a transaction are harder to determine, making it more difficult to make transactions and achieve gains from trade.

Types of Money

Commodity money is a good used as a medium of exchange that has intrinsic value in other uses.

In some form or another, money has been in use for thousands of years. For most of that period, people used commodity money: the medium of exchange was a good, normally gold or silver, that had intrinsic value in other uses. These alternative uses gave commodity money value independent of its role as a medium of exchange. For example, the cigarettes that served as money in World War II prisoner-

Commodity-backed money is a medium of exchange with no intrinsic value whose ultimate value is guaranteed by a promise that it can be converted into valuable goods.

In 1776, when Adam Smith wrote The Wealth of Nations, there was widespread use of paper money in addition to gold or silver coins. Unlike modern dollar bills, however, this paper money consisted of notes issued by privately owned banks, which promised to exchange their notes for gold or silver coins on demand. So the paper currency that initially replaced commodity money was commodity-backed money, a medium of exchange with no intrinsic value whose ultimate value was guaranteed by a promise that it could always be converted into valuable goods on demand.

The big advantage of commodity-

In a famous passage in The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith described paper money as a “waggon-

Fiat money is a medium of exchange whose value derives entirely from its official status as a means of payment.

At this point you may ask: why make any use at all of gold and silver in the monetary system, even to back paper money? In fact, today’s monetary system goes even further than the system Smith admired, having eliminated any role for gold and silver. A Canadian dollar bill isn’t commodity money, and it isn’t even commodity-

Fiat money has two major advantages over commodity-

Fiat money, though, poses some risks. In this chapter’s opening story, we described one such risk—

The larger risk is that governments that can create money whenever they feel like it will be tempted to abuse the privilege. In Chapter 16 we’ll learn how governments sometimes rely too heavily on printing money to pay their bills, leading to high inflation. In this chapter, however, we’ll stay focused on the question of what money is and how it is managed.

Measuring the Money Supply

A monetary aggregate is an overall measure of the money supply.

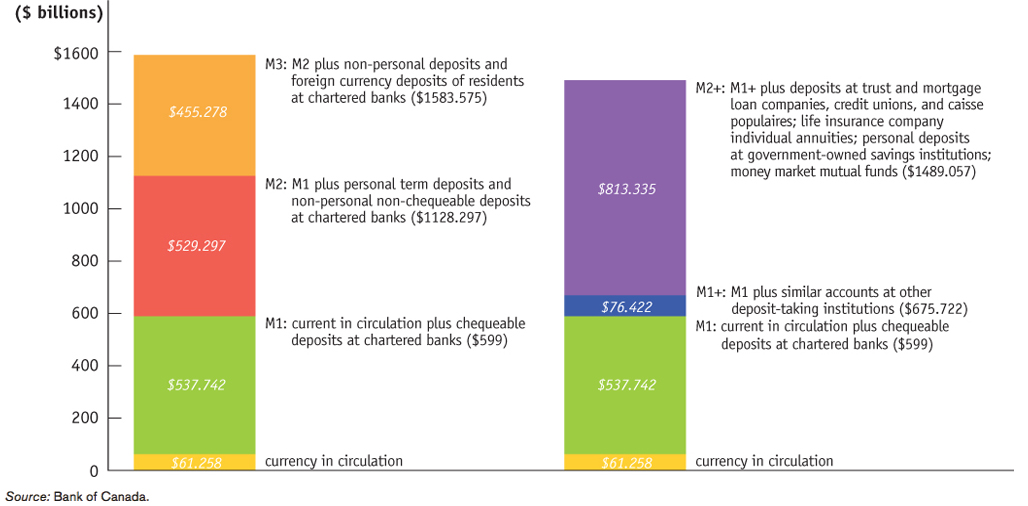

The Bank of Canada (an institution we’ll talk more about shortly) calculates the size of several monetary aggregates, overall measures of the money supply, which differ in how strictly money is defined. These aggregates are known, rather cryptically, as M1, M1+, M2, M2+, and M3. All of these monetary aggregates include currency in circulation and deposits at financial institutions, but each one includes different types of deposits and financial institutions. In general terms, an aggregate without a “+” sign includes only deposits held at chartered banks. An aggregate with a “+” sign includes the deposits at chartered banks plus the same type(s) of deposits at smaller financial institutions, such as trust companies, mortgage and loan companies, credit unions, and caisses populaires.1

WHAT’S NOT IN THE MONEY SUPPLY

Are financial assets like stocks and bonds part of the money supply? No, not under any definition, because they’re not liquid enough.

M1+ consists, roughly speaking, of assets you can use to buy groceries: currency and chequeable deposits (which work as long as your grocery store accepts either cheques or debit cards). Broader definitions of money supply—

By contrast, converting a stock or a bond into cash requires selling the stock or bond—

More specifically, M1, the narrowest definition, consists only of currency in circulation (cash) and all chequeable (or demand) deposits at chartered banks. As the name suggests, demand deposits are bank deposits that can be withdrawn on demand by, for instance, writing cheques against these accounts, debit transactions, online banking, and accessing ATMs. These deposits pay little or no interest. M1+, a broader definition, consists of M1 plus the demand deposits at trust companies, mortgage and loan companies, credit unions, and caisses populaires. M2, the next step up, includes M1 plus the personal term deposits, non-

WHAT’S WITH ALL THE CURRENCY?

Alert readers may be a bit startled by one of the numbers in the money supply (in Figure 14-1)—more than $61 billion of currency in circulation. That’s about $1756 in cash for every man, woman, and child in Canada. How many people do you know who carry $1756 in their wallets? Not many. So where is all that cash?

Part of the answer is that it isn’t in individuals’ wallets—

Economists believe that cash also plays an important role in trans-

Near-moneys are financial assets that can’t be directly used as a medium of exchange but can be readily converted into cash or chequeable deposits.

You may already have noticed that M1 and M1+ include only those assets we use for daily monetary transactions. These assets are the most liquid components of money, or the medium of exchange. However, as the definition of money widens, the monetary aggregates start to include what we call near-moneys. These financial assets cannot be used as a medium of exchange but can be converted into cash or chequing deposits readily. An example is a term deposit, which isn’t chequeable but can be withdrawn at any time before its maturity date by paying a penalty.

Figure 14-1 shows the actual composition of M1, M1+, M2, M2+, and M3 in Canada as of August 2012, in billions of dollars. M1 was valued at about $599.5 billion, with currency in circulation accounting for about 10% and demand deposits accounting for the remainder. In turn, M2 was valued at $1128.3 billion, with M1 accounting for 53%, and savings deposits, non-

THE HISTORY OF THE CANADIAN DOLLAR 2

Canadian paper bills are fiat money, which means they have no intrinsic value and are not backed by anything that has value. But money in Canada wasn’t always like that. In the 1600s and 1700s, “commodity money” prevailed, that is, the money consisted of coins made of metal, such as gold or silver, that did have intrinsic value. These coins came from many lands, including England, France, Portugal, Spain, and Spain’s South American colonies. As you can imagine, this great diversity of currency caused considerable “currency chaos.”

The first banknotes issued in Canada were issued by the Bank of Montreal upon its establishment in 1817. These notes could be redeemed in gold and silver coins upon demand. As more banks became incorporated in Upper and Lower Canada during the 1830s and 1840s, they, too, issued their own banknotes. The banking sector lobbied against the issuing of paper notes by the government because the banks thought this would erode their right to print money—

The move to government-

The next change occurred upon Confederation in 1867, when the Dominion of Canada, consisting of Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick, was created. Banks were brought under national legislation, but they retained the right to issue their own banknotes.

The next crisis occurred in 1914, when World War I began, causing financial panic. There were heavy withdrawals of gold from banks and real concerns that banks would not be able to meet depositors’ demands. To avert a banking collapse, the government temporarily declared banknotes legal tender—

The Great Depression caused the next major change in Canada’s banking system. Public distrust of the banking system and rising political pressure to do something about the depression led the government to create a central bank—

Gold backing for Canadian currency was eliminated in 1940, although Canadian paper currency continued to carry the traditional statement “Will pay the bearer on demand” until 1954. Today’s Bank of Canada notes simply say “This note is legal tender.” They are, in other words, fiat money pure and simple. Their value is backed by the taxing power of the federal government, which helps ensure that not too many notes are issued.

While the Bank of Canada holds the privilege of printing Canadian paper money, it faces the same difficulty that other central banks face with their currencies: people keep trying to make and use fake banknotes. Thus, the Bank of Canada continues to improve the design of banknotes to make them harder to counterfeit. It also works closely with the RCMP to fight counterfeiting.

Quick Review

Money is any asset that can easily be used to purchase goods and services. Currency in circulation and chequeable deposits are both part of the money supply.

Money plays three roles: a medium of exchange, a store of value, and a unit of account.

Historically, money took the form first of commodity money, then of commodity-backed money. Today the dollar is pure fiat money.

The Bank of Canada measures several monetary aggregates: M1, M1+, M2, M2+, and M3. M1 is the narrowest definition of the money supply: it contains the most liquid assets, namely currency in circulation and demand deposits at chartered banks. M1+ includes M1, plus the currency in demand deposits at other financial institutions such as credit unions, trust and mortgage loan companies, caisses populaires, and so on. M2, M2+, and M3 are broader definitions of money supply, which include different kinds of near-moneys such as savings and term deposits, non-

personal deposits, and, in the case of M2+, deposits at other financial institutions of the same type as for M1+.

Check Your Understanding 14-1

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 14-1

Suppose you hold a gift certificate, good for certain products at participating stores. Is this gift certificate money? Why or why not?

The defining characteristic of money is its liquidity: how easily it can be used to purchase goods and services. Although a gift certificate can easily be used to purchase a very defined set of goods or services (the goods or services available at the store issuing the gift certificate), it cannot be used to purchase any other goods or services. A gift certificate is therefore not money, since it cannot easily be used to purchase all goods and services.

Although most bank accounts do pay some interest, depositors can usually get a higher interest rate by buying a guaranteed investment certificate, or GIC. The difference between a GIC and a bank account is that the depositor pays a penalty for withdrawing the money from a GIC before it comes due—

a period of months or even years. GICs are classified as term deposits, so they are counted in M2. Explain why they are not part of M1.

Again, the important characteristic of money is its liquidity: how easily it can be used to purchase goods and services. M1, the narrowest definition of the money supply, contains only currency in circulation and demand deposits (chequable bank deposits at the chartered banks). GICs aren’t chequable—

Explain why a system of commodity-

backed money uses resources more efficiently than a system of commodity money.

Commodity-