14.5 The Evolution of the Canadian Banking System

Up to this point, we have been describing the Canadian banking system5 and how it works. To fully understand that system, however, it is helpful to understand how and why it was created—

The First World War—An Early Crisis in Canadian Banking

Many Canadians are aware that Canada “came of age” during World War I (1914–1918). This phrase usually refers to Canada’s military and political contribution to the war effort. What is less well known is how Canada matured financially at this time.

Before World War I, Canada was on the gold standard, a complex fixed exchange rate arrangement in which member nations’ money was backed by, and exchangeable for, gold. Private Canadian banks in this era were allowed to issue their own banknotes as long as they held a sufficient amount of gold to back their value. These notes circulated along with Dominion of Canada notes to constitute the currency of the country. Also important during this period of our history is the fact that Canada did not have a central bank. In the days just before war was declared, Canadian banks experienced large demands for conversion of currency and deposits into gold, which led to concerns of bank runs. With no lender of last resort, banks were required by law to close if they could not meet depositor demand for gold or Dominion notes.

Rumours that a bank had insufficient gold or Dominion notes to satisfy demands for withdrawal or conversion could quickly lead to a bank run. A bank run could spark a contagion, setting off runs at other nearby banks, sowing widespread panic and devastation in the local economy. So, to protect the banks, the government enacted several laws. First, the government ordered that all the notes issued by Canadian banks were now legal tender. This is important as it gave these notes the same legal status as gold, Dominion of Canada notes, and all metallic coins minted in Canada when it came to settling transactions. Next, the government allowed banks to issue more notes. At the same time, the lender of last resort function was introduced, so the Treasury Board was allowed to make advances, which are loans made to private banks in Dominion notes, against securities these banks pledged as collateral to the minister of finance. Lastly, the government suspended the conversion of Dominion notes into gold—

Canada did return to the gold standard temporarily, from 1926 to 1933, but this new standard differed from the pre-

When the Great Depression hit the world in 1929, Canada stuck with the gold standard and the fixed exchange rate it created via international movements of gold. But Canada did try to discourage exports of gold. In 1931, the United Kingdom abandoned the gold standard and let the pound float in currency exchange markets. This created significant turmoil on world financial markets. The world money market froze up, as potential lenders became so fearful of making bad loans they declined to enter into almost all loan requests. Canada found that it could not obtain even short-

A commercial bank is one that accepts deposits and is covered by deposit insurance.

Following the Wall Street stock market crash of 1929, the Canadian economy shrank significantly. If the federal government had advanced more money to banks, the money supply would have increased; but, as it was, the government provided little or no voluntary monetary stimulus to help the economy recover. Commercial banks were allowed to request advances from the government, but chose not to do so. This was because the government did not lower the interest rate on advances, causing banks to fear that they might not be able to repay them. Consequently, the money supply contracted, instead of expanding. Nor did sticking with the gold standard, even notionally, allow the Canadian dollar to depreciate enough to stimulate net exports sufficiently to help expand the economy and create jobs.

Responding to the Great Depression: The Creation of the Bank of Canada

Unfortunately, as is now well understood by economic historians, the falling money supply and shrinking trade balance of the early 1930s acted to significantly worsen and prolong the economic slump now known as the Great Depression. By 1933, the government had realized some of its policy mistakes and attempted to correct them. In this year, Canada left the gold standard, lowered the rate of interest on advances, and set up a royal commission to study the financial system and to consider whether Canada should establish its own central bank.

There were plenty of arguments against a central bank: Canada’s existing financial structure was sound but its debt was too high; Canada lacked the constitutional authority to launch such an entity; creating a central bank during an economic crisis was unwise; such an institution might act as an impediment to the eventual return to the gold standard; the American central bank had been unable to counteract the Depression in the United States; Canada lacked the expertise to operate such as institution; Canada lacked the proper domestic money market that a central bank needs to function; Canadian banks were stable and did not need a central bank to help support them; and so on. In particular, Canadian banks opposed the idea because they feared their profits might fall once a central bank became the sole issuer of domestic banknotes.

However, the commission did recommend the creation of a central bank, and in 1935 the Bank of Canada was established. Now Canada had a single institution with the authority to conduct monetary policy, issue all Canadian banknotes, manage the finances of the federal government, regulate the financial system, and act as the lender of last resort. Authority over monetary policy allowed the central bank to change interest rates via interventions in the money market, initiate loans to banks, intervene in the foreign exchange market to influence the exchange rate, and promote the economic and financial welfare of the nation by attempting to support full employment and stable prices.

It is interesting to note that in 1933 the United States introduced deposit insurance owing to widespread bank runs during the Depression. Why didn’t Canada also introduce deposit insurance then? It’s because at that time Canada’s banking system was much different: our system spread financial risks out more evenly across the nation. As a result, Canada had fewer severe banking disruptions than the U.S. This is why Canadians felt deposit insurance was not needed to stabilize the banking sector, and deposit insurance was not introduced in Canada until 1967.

The U.S. Financial Crisis of 2008

The financial crisis of 2008 had some of the same features of the earlier financial crises. It involved U.S. institutions that were not as strictly regulated as deposit-taking banks, excessive speculation, and a U.S. government that was reluctant to take aggressive action until the scale of the devastation became clear. In addition, by the late 1990s, advances in technology and financial innovation had created yet another systemic weakness that played a central role in 2008. The story of Long-Term Capital Management, or LTCM, highlights these problems.

Long-Term Capital (Mis)Management Created in 1994, LTCM was a U.S. hedge fund, a private investment partnership open only to wealthy individuals and institutions. In the United States, hedge funds are virtually unregulated, allowing for much riskier investments than with mutual funds, which are open to the average investor. Using vast amounts of leverage—that is, borrowed money—to increase its returns, LTCM used sophisticated computer models to make money by taking advantage of small differences in asset prices in global financial markets to buy at a lower price and sell at a higher price. In one year, LTCM made a return as high as 40%.

A financial institution engages in leverage when it finances its investments with borrowed funds.

LTCM was also heavily involved in derivatives, complex financial instruments that are constructed—derived—from the obligations of more basic financial assets. Derivatives are popular investment tools because they are cheaper to trade than basic financial assets and can be constructed to suit a buyer’s or seller’s particular needs. Yet their complexity can make it extremely hard to measure their value. LTCM believed that its computer models allowed it to accurately gauge the risk in the huge bets that it was undertaking in derivatives using borrowed money.

However, LTCM’s computer models hadn’t factored in a series of financial crises in Asia and in Russia during 1997 and 1998. Through its large borrowing, LTCM had become such a big player in global financial markets that attempts to sell its assets depressed the prices of what it was trying to sell. As the markets fell around the world and LTCM’s panic-stricken investors demanded the return of their funds, LTCM’s losses mounted as it tried to sell assets to satisfy those demands. Quickly, its operations collapsed because it could no longer borrow money and other parties refused to trade with it. Financial markets around the world froze in panic.

The Federal Reserve realized that allowing LTCM’s remaining assets to be sold at panic-stricken prices presented a grave risk to the entire financial system through the balance sheet effect: as sales of assets by LTCM depressed asset prices all over the world, other firms would see the value of their balance sheets fall as assets held on these balance sheets declined in value. Moreover, falling asset prices meant the value of assets held by borrowers on their balance sheets could fall below a critical threshold, leading to a default on the terms of their credit contracts and forcing creditors to call in their loans. This in turn would lead to more sales of assets as borrowers tried to raise cash to repay their loans, more credit defaults, and more loans called in, creating a vicious cycle of deleveraging.

The balance sheet effect is the reduction in a firm’s net worth due to falling asset prices.

A vicious cycle of deleveraging takes place when asset sales to cover losses produce negative balance sheet effects on other firms and force creditors to call in their loans, forcing sales of more assets and causing further declines in asset prices.

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York arranged a $3.625 billion bailout of LTCM in 1998, in which other private institutions took on shares of LTCM’s assets and obligations, liquidated them in an orderly manner, and eventually turned a small profit. Quick action by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York prevented LTCM from sparking a contagion, yet virtually all of LTCM’s investors were wiped out.

Sub-prime Lending and the Housing Bubble After the LTCM crisis, U.S. financial markets stabilized. They remained more or less stable even as stock prices fell sharply from 2000 to 2002 and the U.S. economy went into recession. During the recovery from the 2001 recession, however, the seeds for another financial crisis were planted.

The story begins with low interest rates: by 2003, U.S. interest rates were at historically low levels, partly because of Federal Reserve policy and partly because of large inflows of capital from other countries, especially China. These low interest rates helped cause a boom in housing, which in turn led the U.S. economy out of recession. As housing boomed, however, financial institutions began taking on growing risks—risks that were not well understood.

Traditionally, people could only borrow money to buy homes if they could show that they had sufficient income to meet the mortgage payments. Sub-prime lending, lending money for buying homes to people who usually wouldn’t qualify for such loans, represented only a minor part of overall lending. But in the booming housing market of 2003–2006, sub-prime lending started to seem like a safe bet. Since housing prices kept rising, borrowers who couldn’t make their mortgage payments could always pay off their mortgages, if necessary, by selling their homes. As a result, sub-prime lending exploded.

Sub-prime lending is lending to homebuyers who don’t meet the usual criteria for being able to afford their payments.

Who was making these sub-prime loans? For the most part, it wasn’t American traditional banks that were lending out depositors’ money. Instead, most of the loans were being made by “loan originators,” who quickly sold mortgages to other investors. These sales were made possible by a process known as securitization: financial institutions assembled pools of loans and sold shares in the income from these pools. These shares were considered relatively safe investments, since it was considered unlikely that large numbers of homebuyers would default on their payments all at the same time.

In securitization, a pool of loans is assembled and shares of that pool are sold to investors.

But that’s exactly what happened. The housing boom turned out to be a bubble, and when home prices started falling in late 2006, many sub-prime borrowers could neither make their mortgage payments nor sell their houses for enough to pay off their mortgages. As a result, investors in securities backed by sub-prime mortgages started taking heavy losses. Many of the mortgage-backed assets were held by financial institutions, including banks and other institutions playing bank-like roles. As in previous crises, these “non-bank banks” were less regulated than commercial banks, which allowed them to offer higher returns to investors but left them extremely vulnerable in a crisis. Mortgage-related losses, in turn, led to a collapse of trust in the financial system.

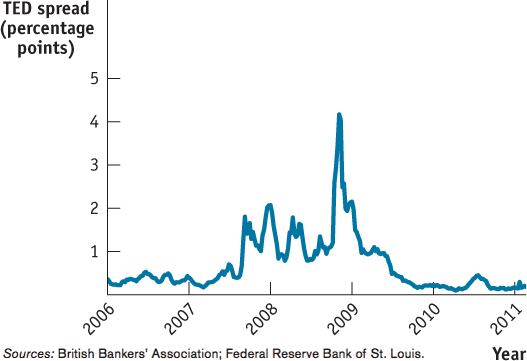

Figure 14-14 shows one measure of this loss of trust: the TED spread, which is the difference between the interest rate on three-month loans that banks make to each other and the interest rate the U.S. federal government pays on three-month bonds. (“TED” is an acronym formed from the “T” of treasury bills and the “ED” of euro dollars.) Since U.S. government bonds are considered extremely safe, the TED spread shows how much risk American banks think they’re taking on when lending to each other. Normally the spread is around a quarter of a percentage point, but it shot up in August 2007 and surged to an unprecedented 4.58 percentage points in October 2008, before returning to more normal levels in mid-2009.

Crisis and Response The collapse of trust in the financial system, combined with the large losses suffered by some financial firms, led to a severe cycle of deleveraging and a credit crunch for the U.S. economy as a whole. American firms found it difficult to borrow, even for short-term operations; individuals found home loans unavailable and credit card limits reduced. These symptoms were shared by individuals, firms, and governments worldwide, thanks to our interconnected global financial system.

Overall, the negative economic effect of the financial crisis bore a distinct and troubling resemblance to the effects of the banking crisis of the early 1930s, which helped cause the Great Depression. Policy-makers noticed the resemblance and tried to prevent a repeat performance. Beginning in August 2007, the Federal Reserve engaged in a series of efforts to provide cash to the financial system, lending funds to a widening range of institutions and buying private-sector debt. The Fed and the U.S. Treasury Department also stepped in to rescue individual firms that were deemed too crucial to be allowed to fail, such as the investment bank Bear Stearns and the insurance company AIG.

An investment bank is one that trades in financial assets and is not covered by deposit insurance.

In September 2008, however, American policy-makers decided that one major investment bank, Lehman Brothers, could be allowed to fail. They quickly regretted the decision. Within days of Lehman’s failure, widespread panic gripped global financial markets, as illustrated by the surge in the TED spread at this time, as shown in Figure 14-14. In response to the intensified crisis, the U.S. government intervened further to support the financial system, as the U.S. Treasury began “injecting” capital into banks. Injecting capital, in practice, meant that the U.S. government would supply cash to banks in return for shares—in effect, partially nationalizing the financial system.

By the fall of 2010, the U.S. financial system appeared to be stabilized, and major institutions had repaid much of the money the U.S. federal government had injected during the crisis. It was generally expected that American taxpayers would end up losing little if any of this stimulus money. However, the recovery of the banks was not matched by a successful turnaround for the overall American economy: although the recession that began in December 2007 officially ended in June 2009, U.S. unemployment remained stubbornly high.

The Federal Reserve responded to this troubled situation with novel forms of open-market operations. Conventional open-market operations are limited to short-term government debt, but the Fed believed that this was no longer enough. It provided massive liquidity through discount window lending, as well as undertaking so-called quantitative easing, the buying of large quantities of other assets, mainly long-term government debt and the debts of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, government-sponsored agencies that support home lending.

Like earlier crises, the crisis of 2008 led to changes in U.S. and world banking regulation. Since much of the crisis originated in non-traditional bank institutions, the crisis of 2008 indicated that a wider safety net and broader regulation were needed in the financial sector. And such reforms were implemented. In the U.S., in July 2010, the Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, known as the Dodd-Frank bill, became law. The biggest U.S. financial reform since the 1930s, this bill resulted in a new agency, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, to protect borrowers. In 2012, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision reached an agreement on detailed measures to strengthen the regulation, supervision, and risk management of the world’s banking sector. This package of measures, known as Basel III, will, in a nutshell, require a significant rise in the banking industry’s liquid capital requirements so that these institutions will become less prone to banking crises. Will these changes succeed in heading off future banking crises? Time will tell.

WHY ARE CANADA’S BANKS MORE STABLE?

The 2008 crisis in America’s banks caused widespread financial and economic suffering in many nations, including our own. As severe as our downturn was—the most significant slump in Canada since the Great Depression—it easily could have been much worse if not for some important differences in our banking sector.

In 2012, for the fifth year in a row, the World Economic Forum ranked Canada’s banking system as the most sound in the world. How is this possible? Is this something new? Not really. Historically the Canadian banking sector has always been very stable. Bank failures have been quite rare in Canada, even during market crashes, depressions, wars, and other financial turmoil. The stability of Canadian banks comes from important structural differences between how banks are set up and operated here relative to other jurisdictions. To quote the Canadian Bankers Association (CBA), speaking on behalf of their members:

Canada’s banks are well managed, well regulated, and well capitalized. We play by the rules and our national banking system is a key strength. By diversifying regional risk, a downturn in an individual economic sector is balanced since funds can be moved from areas of excess deposits to regions where growth is creating demand for new credit.

Banks in Canada make lending decisions on a case-by-case basis, extending credit to those who have the capacity to repay their loans. This prudent approach is a key reason why banks in Canada have largely avoided the problems that have plagued banks elsewhere.6

For more than one hundred years the Canadian banking system has been set up in such a way that it is more concentrated, sometimes called more oligopolistic, than those of some other jurisdictions, such as the United States. This means that the Canadian banking system has been dominated for many decades by large national players who are well capitalized and diversified; thus, they are more resilient in the face of financial market fluctuations. The government, in return for allowing such concentration of market power, has demanded that firms face regulatory oversight in order to ensure the system is both sound and meets the needs of society.

The American banking system is considerably different from the Canadian system. Whereas Canada has a few large banks, the U.S. has a great many small ones. This difference may be partly the result of an American desire for greater competition and a distrust of concentrating too much market power in the hands of large firms. Also, until recently, American laws have prevented banks in one state from operating in another. As a result, U.S. banks are often not capitalized or diversified as well as Canadian banks are, so they are more vulnerable to significant financial distress, such as bank runs.

As the CBA notes, Canadian banks have historically acted more conservatively than U.S. banks when it comes to making loans. Key regulatory differences between Canada and the United States generally include the following:

Canada requires higher minimum credit scores to obtain a mortgage.

Canada requires higher minimum down payments on mortgages.

Canada requires mortgage default insurance on all loans with down payments less than 20%.

Maximum amortization periods are shorter in Canada.

Interest on mortgages for owner-occupied housing is tax deductible in the U.S., but not in Canada.

It is more costly to default on a mortgage in Canada than in the U.S. Unlike in the U.S., a Canadian homeowner faced with negative equity cannot “walk away.”

Canada has fewer small (as a percentage of loans made) unregulated mortgage lenders than in the U.S.

Canadian lenders make fewer sub-prime loans than their American counterparts.

Canadian lenders are less likely to shift the default risk of their portfolio of mortgage loans to other parties by selling mortgage-backed securities (bonds backed by the cash flow coming from the mortgages). This is partly owing to mortgage default insurance and a less well developed market for asset-backed securities.

These differences make the Canadian financial sector less vulnerable (or more resilient) to any adverse shock in the housing market. First, it is relatively harder for Canadians with low credit ratings or a bad credit history to get mortgages. The relatively higher costs of carrying mortgages, as a result of mortgage default insurance requirements, shorter amortization periods, and the inability to deduct the interest paid on owner-occupied mortgages from taxes, discourage Canadians from borrowing excessively. All these rules help to lower the likelihood of default and to reduce the losses banks may face when defaults occur. These differences help explain why the Canadian market for mortgages is more conservative than the U.S. market, which also explains why U.S. housing prices are more likely to create a harmful financial bubble.

This does not mean that housing price bubbles are unknown in Canada (recall our look in Chapter 10 at the potential housing bubble in Vancouver), but that their risks are lessened. In fact, since the recession of 2008–2009 caused by the bursting of the U.S. housing price bubble in 2006–2007, the Canadian government has been trying to reduce the possibility of a similar bubble bursting here. The Bank of Canada has repeatedly warned Canadians to be aware of the ballooning level of household debt that has, in recent years, climbed higher and higher as a percent of income. To try to slow the market for home sales and, with it, the rise in housing prices, the federal minister of finance has on several occasions adopted measures to make it harder to qualify for a mortgage. These measures have started to take effect: as the volume of home sales has dropped and the rate of increase in home prices has slowed and even declined in some markets.

Were these measures enough? Was there already a nationwide housing bubble and did these measures help to slowly deflate it? Might it still burst at some point? Or, was there no such bubble because these measures helped to prevent its creation? Only the passage of time will reveal whether high Canadian home prices and household indebtedness end up creating significant financial hardship and perhaps another recession.

Quick Review

The Bank of Canada was created in response to poor monetary policy during the Great Depression.

Canada did not suffer widespread bank runs in the early 1930s, as the United States did. Nonetheless, many Canadians felt a properly run central bank would mitigate the risk of such bank runs happening in Canada.

During the mid-1990s, the hedge fund LTCM used huge amounts of leverage to speculate in global markets, incurred massive losses, and collapsed. In selling assets to cover its losses, LTCM caused balance sheet effects for firms around the world. To prevent a vicious cycle of deleveraging, the New York Fed coordinated a private bailout.

In the mid-2000s, loans from sub-prime lending spread through the world financial system via securitization, leading to a financial crisis that spread around the entire world. The U.S. Federal Reserve responded by injecting cash into financial institutions and buying private debt. The Bank of Canada responded in a very similar way.

In recent years regulators in the U.S. and around the world have revised financial regulation in an attempt to prevent repeats of the 2008 crisis.

Check Your Understanding 14-5

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 14-5

What structural differences between the Canadian and American banking sectors led to many bank runs in the U.S. and none in Canada during the Great Depression?

It is because the financial risks were spread out more evenly across Canada than in the United States. In the United States, the financial risks were localized as the American banks were localized banks, i.e., they were providing services in specific state. In Canada, banks were operated across the country, which allowed them to diversify their risks. Also, the Canadian banking system is more concentrated than the American system, so the Canadian banks are well capitalized and diversified. Therefore, there were fewer and smaller sized bank runs in Canada than in the United States.

What is a housing price bubble? Who benefits from the creation of such bubbles? Why should society be concerned about such bubbles arising? What role, if any, might the government play in helping to either create or avoid a housing price bubble?

A home price bubble refers to the situation in which the housing prices keep rising to unrealistic levels that they suddenly collapse. Real estate developers who can sell the houses at higher prices and financial institutions that quickly sold mortgages to other investors would gain from the creation of these bubbles. The society should be concerned about home price bubbles because the bursting of these bubbles could cause huge damage to the economy such as the collapse of trust in the financial system, huge losses incurred by financial institutions, and all these lead to the vicious cycle of deleveraging and the tightening in the credit market.

Describe the balance sheet effect. Describe the vicious cycle of deleveraging. Why does the government sometimes need to step in to halt a vicious cycle of deleveraging?

The balance sheet effect occurs when asset sales cause declines in asset prices, which then reduce the value of other firms’ net worth as the value of the assets on their balance sheets declines. In the vicious cycle of deleveraging, the balance sheet effect on firms forces their creditors to call in their loan contracts, forcing the firms to sell assets to pay back their loans, leading to further asset sales and price declines. Because the vicious cycle of deleveraging occurs across different firms and no single firm can stop it, it is necessary for the government to step in to stop it.

The Perfect Gift: Cash or a Gift Card?

On average, Canadians spend about $200 on gift cards per year. What could be more simple and useful, than allowing the recipient to choose what he or she wants? And isn’t a gift card more personal than cash or a cheque stuffed in an envelope?

Yet several websites are now making a profit from the fact that gift card recipients are often willing to sell their cards at a discount—sometimes at a fairly sizable discount—to turn them into cold, impersonal dollars and cents.

CardSwap.ca is one such site. At the time of writing, it offers to pay cash to a seller of an Esso Imperial Oil gift card equivalent to 92% of the card’s face value (for example, the seller of a card with a value of $100 would receive $92 in cash). But it offers cash equal to only 60% of a Hakim Optical card’s face value. CardSwap.ca profits by reselling the card at a premium over what it paid; for example, it buys an Aeropostale card for 70% of its face value and then resells it for almost 100% of its face value. Many consumers are, in fact, willing to sell at a sizable discount to turn their unwanted gift cards into cash.

Retailers are eager to promote the use of gift cards over cash. According to market studies, 10% to 15% of gift cards are never redeemed. Those unredeemed dollars accrue to the retailer, making gift cards a highly profitable line of business. With more than $6 billion worth of gift cards sold in Canada annually, this places the value of “breakage,” the amount of a gift card that accrues to the retailer rather than to the cardholder, at more than $600 million in 2012. Breakage also occurs when cardholders redeem only a portion of a gift card. For instance, they spend only $47 of a $50 card, figuring it’s not worth the effort to return to the store to spend that last $3.

In addition to breakage, retailers have found that gift cards are profitable in other ways. Retailers benefit when customers intent on using up the value of their gift card actually end up spending more than the card’s face value, sometimes spending even more than they would have without the gift card. Customers who use gift cards are more likely to make impulse purchases than customers who use other means of payment. And they are more likely to buy items at full price rather than articles that are on sale. Also, when retailers sell the gift card, they immediately get access to the full amount of the funds provided to charge the card and can use these funds interest free until the card is used. If a retailer goes out of business, the value of any outstanding gift cards disappears with it.

Previously, sellers commonly rewarded customers loyalty with mail-in rebates—actual cheques to the customer that repaid part of the original cost of the purchase. Now retailers often prefer to issue gift cards for the same value instead. As one commentator noted in explaining why, “Nobody neglects to spend cash.”

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

Why are gift card owners willing to sell their cards for less than their face value?

Why are gift card owners willing to sell their cards for less than their face value?

Why do gift cards for Esso sell for a smaller discount than Hakim Optical?

Why do gift cards for Esso sell for a smaller discount than Hakim Optical?

Use your answer from Question 2 to explain why cash never “sells” at a discount.

Use your answer from Question 2 to explain why cash never “sells” at a discount.

Explain why retailers prefer to reward loyal customers with gift cards instead of mail-in rebates.

Explain why retailers prefer to reward loyal customers with gift cards instead of mail-in rebates.

Recent legislation in several provinces has restricted retailers’ ability to impose fees and expiration dates on their gift cards and mandated greater disclosure of their terms. Why do you think governments enacted such legislation?

Recent legislation in several provinces has restricted retailers’ ability to impose fees and expiration dates on their gift cards and mandated greater disclosure of their terms. Why do you think governments enacted such legislation?