14.8 PROBLEMS

For each of the following transactions, what is the initial effect (increase or decrease) on M1? On M2? On M2+?

You sell a few shares of stock and put the proceeds into your savings account in a chartered bank.

You sell a few shares of stock and put the proceeds into your chequing account in a chartered bank.

You transfer money from your savings account to your chequing account in a chartered bank.

You discover $0.25 under the floor mat in your car and deposit it in your chequing account.

You discover $0.25 under the floor mat in your car and deposit it in your savings account in a credit union.

There are three types of money: commodity money, commodity-

backed money, and fiat money. Which type of money is used in each of the following situations? Bottles of rum were used to pay for goods in colonial Australia.

Salt was used in many European countries as a medium of exchange.

For a brief time, Germany used paper money (the “Rye Mark”) that could be redeemed for a certain amount of rye, a type of grain.

The city of Kamloops, British Columbia, prints its own currency, the Kamloops dollar, which can be used to purchase local goods and services.

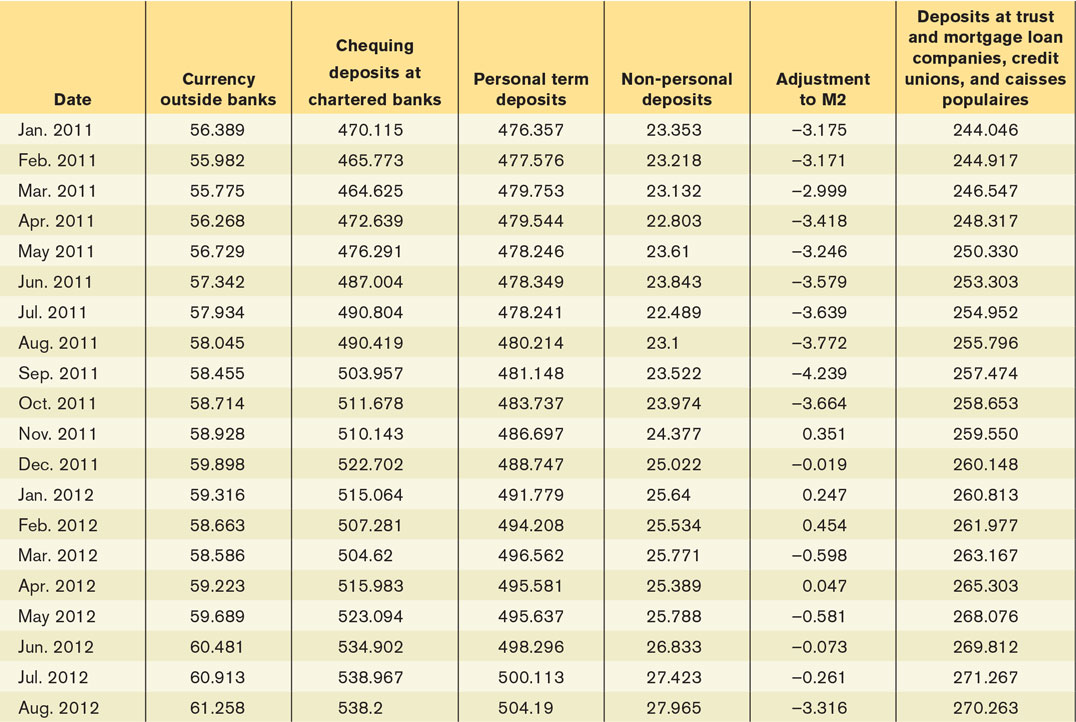

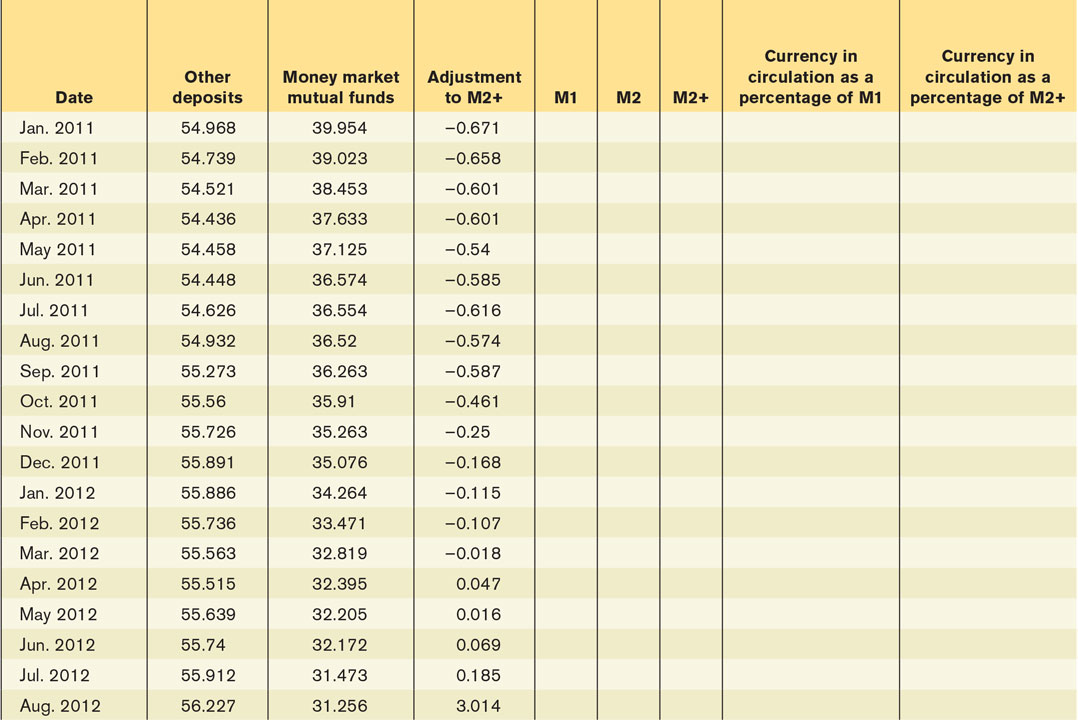

The table below shows the components of M1, M2, and M2+ in billions of dollars from January 2011 to August 2012 as published in the Bank of Canada’s Weekly Financial Statistics on November 16, 2012. Complete the table by calculating M1, M2, M2+, currency in circulation as a percentage of M1, and currency in circulation as a percentage of M2+. What trends or patterns about M1, M2, M2+, currency in circulation as a percentage of M1, and currency in circulation as a percentage of M2+ do you see? What might account for these trends?

Indicate whether each of the following is part of M1, M2, M2+, or none of them:

$95 on your campus meal card

$0.55 in the change cup of your car

$1663 in your savings account in a credit union

$459 in your chequing account in a chartered bank

100 shares of stock worth $4000

A $1000 line of credit on your Sears credit card

Tracy Williams deposits $500 that was in her sock drawer into a chequing account at the local bank.

How does the deposit initially change the T-

account of the local bank? How does it change the money supply? If the bank maintains a reserve ratio of 10%, how will it respond to the new deposit?

If every time the bank makes a loan, the loan results in a new chequeable deposit in a different bank equal to the amount of the loan, by how much could the total money supply in the economy expand in response to Tracy’s initial cash deposit of $500?

If every time the bank makes a loan, the loan results in a new chequeable deposit in a different bank equal to the amount of the loan and the bank maintains a reserve ratio of 5%, by how much could the money supply expand in response to Tracy’s initial cash deposit of $500?

Source: Bank of Canada.

Ryan Cozzens withdraws $400 from his chequing account at the local bank and keeps it in his wallet.

How will the withdrawal change the T-

account of the local bank and the money supply? If the bank maintains a reserve ratio of 10%, how will it respond to the withdrawal? Assume that the bank responds to insufficient reserves by reducing the amount of deposits it holds until its level of reserves satisfies its desired reserve ratio. The bank reduces its deposits by calling in some of its loans, forcing borrowers to pay back these loans by taking cash from their chequing deposits (at the same bank) to make repayment.

If every time the bank decreases its loans, chequeable deposits fall by the amount of the loan, by how much will the money supply in the economy contract in response to Ryan’s withdrawal of $400?

If every time the bank decreases its loans, chequeable deposits fall by the amount of the loan and the bank maintains a desired reserve ratio of 20%, by how much will the money supply contract in response to a withdrawal of $400?

The government of Eastlandia uses measures of monetary aggregates similar to those used by Canada, and the commercial banks in Eastlandia hold a desired reserve ratio of 10%. Given the following information, answer the questions below.

Bank deposits at the central bank = $200 million

Currency held by public = $150 million

Currency in bank vaults = $100 million

Chequeable deposits = $500 million

What is M1?

What is the monetary base?

Are the commercial banks holding excess reserves?

Can the commercial banks increase chequeable deposits? If yes, by how much can chequeable deposits increase?

What will happen to the money supply under the following circumstances in a chequeable-

deposits- only system? The desired reserve ratio is 25%, and a depositor withdraws $700 from his chequeable deposit.

The desired reserve ratio is 5%, and a depositor withdraws $700 from his chequeable deposit.

The desired reserve ratio is 20%, and a customer deposits $750 to her chequeable deposit.

The desired reserve ratio is 10%, and a customer deposits $600 to her chequeable deposit.

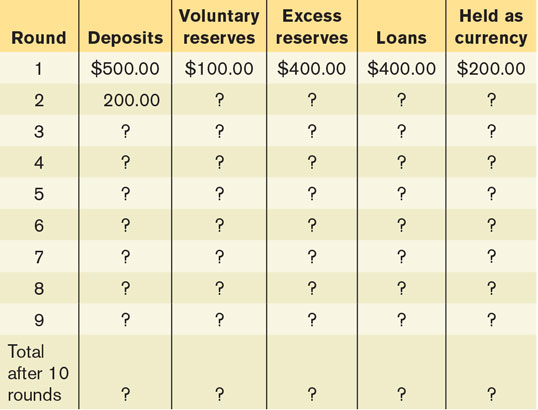

In Westlandia, the public holds 50% of M1 in the form of currency, and the voluntary reserve ratio is 20%. Estimate how much the money supply will increase in response to a new cash deposit of $500 by completing the accompanying table. (Hint: The first row shows that the bank must hold $100 in minimum reserves—

20% of the $500 deposit— against this deposit, leaving $400 in excess reserves that can be loaned out. However, since the public wants to hold 50% of the loan in currency, only $400 × 0.5 = $200 of the loan will be deposited in round 2 from the loan granted in round 1.) How does your answer compare to an economy in which the total amount of the loan is deposited in the banking system and the public doesn’t hold any of the loan in currency? What does this imply about the relationship between the public’s desire for holding currency and the money multiplier?

Although the Bank of Canada does not impose a minimum reserve ratio on the banking sector, the central bank of Albernia does. The commercial banks of Albernia have $100 million in reserves and $1000 million in chequeable deposits; the initial required reserve ratio is 10%. The commercial banks follow a policy of holding no excess reserves. The public holds no currency, only chequeable deposits in the banking system.

How will the money supply change if the required reserve ratio falls to 5%?

How will the money supply change if the required reserve ratio rises to 25%?

Show the changes to the T-

accounts for the Bank of Canada and for commercial banks when the Bank of Canada buys $50 million in treasury bills. If the public holds a fixed amount of currency (so that all loans create an equal amount of deposits in the banking system), the minimum reserve ratio is 10%, and banks hold no excess reserves, by how much will deposits in the commercial banks change? By how much will the money supply change? Show the final changes to the T- account for commercial banks when the money supply changes by this amount.

Show the changes to the T-

accounts for the Bank of Canada and for commercial banks when the Bank of Canada sells $30 million in treasury bills. If the public holds a fixed amount of currency (so that all new loans create an equal amount of chequeable deposits in the banking system) and the minimum reserve ratio is 5%, by how much will chequeable deposits in the commercial banks change? By how much will the money supply change? Show the final changes to the T- account for the commercial banks when the money supply changes by this amount.

In 2011, the RCMP estimated that at least $2.6 million of counterfeit Canadian banknotes were in circulation.

Why do Canadian taxpayers lose because of these counterfeit notes?

As of December 2011, the interest rate earned on one-

year Canadian treasury bills was 1.07%. At a 1.07% rate of interest, what amount of money are Canadian taxpayers losing per year because of these $2.6 million in counterfeit notes?

As Figure 14-13 shows, the portion of the Bank of Canada’s assets made up of Canadian government treasury bills and bonds declined in late 2008. Go to www.statcan.gc.ca. Under “Search,” click on “Specialized search tools” then click on “CANSIM.” In the search line enter “Table 176-0010” and click on the search tab. This will provide you a table of the month-

end assets and liabilities of the Bank of Canada for the most recent few months. To expand the view to time periods further into the past click on the “Add/Remove data” tab and follow the instructions. Under the “Total assets” portion of the table, look in the “Total assets” row. What amount is displayed next to “Total assets”? What amount is displayed next to “Government of Canada, Treasury Bills”? What amount is displayed next to “Government of Canada, bonds”? What percent of the Bank of Canada’s total assets are made up of Canadian government treasury bills? What percent are made up of Canadian government treasury bonds?

Do the Bank of Canada’s assets consist primarily of Canadian government treasury securities, as they did in January 2007, the beginning of the graph in Figure 14-13, or does the Bank of Canada still own a large number of other assets, as it did in mid-

2009, in the middle of the graph in Figure 14-13? In particular, does the Bank of Canada have a figure near zero in the asset rows entitled “Loans and receivables, advances to members of the Canadian Payments Association” and “Loans and receivables, securities purchased under resale agreements”? Or are these two figures a significant percentage of the Bank of Canada’s total assets as they were in 2009 and much of 2010?