15.2 Money and Interest Rates

Central Banks Announce Coordinated Interest Rate Reductions

Throughout the current financial crisis, central banks have engaged in continuous close consultation and have cooperated in unprecedented joint actions such as the provision of liquidity to reduce strains in financial markets. Inflationary pressures have started to moderate in a number of countries, partly reflecting a marked decline in energy and other commodity prices. Inflation expectations are diminishing and remain anchored to price stability. The recent intensification of the financial crisis has augmented the downside risks to growth and thus has diminished further the upside risks to price stability.

Some easing of global monetary conditions is therefore warranted. Accordingly, the Bank of Canada, the Bank of England, the European Central Bank, the Federal Reserve, Sveriges Riksbank, and the Swiss National Bank are today announcing reductions in policy interest rates. The Bank of Japan expresses its strong support of these policy actions.

Bank of Canada lowers overnight rate target by ½ percentage point to 2½ per cent.

The Bank of Canada today announced that it is lowering its target for the overnight rate by ½ percentage point to 2½ per cent. The operating band for the overnight rate is correspondingly lowered, and the Bank Rate is now 2¾ per cent.

The intensification of the global financial crisis is having a marked impact on all countries. In recent weeks conditions in global financial markets have deteriorated sharply, the U.S. economy has weakened further, and commodity prices have fallen abruptly.

As a result of these developments, credit conditions in Canada have tightened significantly, despite the relative health of our financial institutions. Weaker growth in the United States and other important trading partners will increase the drag on the Canadian economy coming from net exports. The deterioration of our terms of trade will act to moderate the growth of domestic demand. While the recent depreciation of the Canadian dollar will help cushion the effects of the weaker global outlook on the domestic economy, it will not completely offset them.

Below-

In view of these developments, the Bank of Canada decided to join other major central banks and lower its target for the overnight rate by 50 basis points today. This action will provide timely and significant support to the Canadian economy. The Bank will continue to monitor carefully economic and financial developments, along with the evolution of risks, in judging whether any further action might be required to achieve its 2 per cent inflation target over the medium term.2

So read a press release from the Bank of Canada issued on October 8, 2008. The BOC lowered the overnight rate by 0.5 percentage points in an attempt to prevent the deepening of the recession.3 What was special about this announcement was that the BOC lowered its target for the overnight rate on a date that was outside its fixed schedule of dates for policy interest rate announcements. The press release indicated that this surprise interest rate cut was part of a coordinated effort by central banks around the world that were attempting to loosen the tight financial market and to support the weakening global economy. We learned about the overnight rate in Chapter 14: it is the rate at which banks lend excess reserves to each other generally for one business day or less (unless a longer term is negotiated). The BOC sets a target for the overnight rate, and then it’s up to the BOC’s officials to achieve that target. This is done by open-

Once the BOC sets the target for the overnight rate, other key interest rates, such as the prime rate, rates on GICs, and mortgage rates, will move in the same direction, and these interest rates tend to change in proportion to the change in the target for the overnight rate. How does the BOC go about achieving a target for the overnight rate? And more to the point, how is the BOC able to affect interest rates at all?

The Equilibrium Interest Rate

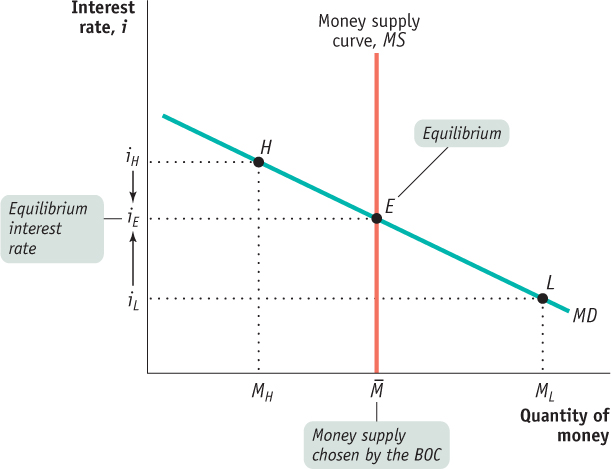

According to the liquidity preference model of the interest rate, the interest rate is determined by the supply and demand for money.

Recall that, for simplicity, we’re assuming there is only one interest rate paid on non-

The money supply curve shows how the quantity of money supplied varies with the interest rate.

. The money market is in equilibrium at the interest rate iE: the quantity of money demanded by the public is equal to

. The money market is in equilibrium at the interest rate iE: the quantity of money demanded by the public is equal to  , the quantity of money supplied.

, the quantity of money supplied.At a point such as L, the interest rate, iL, is below iE and the corresponding quantity of money demanded, ML, exceeds the money supply,

. In an attempt to shift their wealth out of non-

. In an attempt to shift their wealth out of non- . In an attempt to shift out of money holdings into non-

. In an attempt to shift out of money holdings into non-In Chapter 14 we learned how the Bank of Canada can increase or decrease the money supply: it usually does this through open- . The money market equilibrium is at E, where MS and MD cross. At this point the quantity of money demanded equals the money supply,

. The money market equilibrium is at E, where MS and MD cross. At this point the quantity of money demanded equals the money supply,  , leading to an equilibrium interest rate of iE.

, leading to an equilibrium interest rate of iE.

To understand why iE is the equilibrium interest rate, consider what happens if the money market is at a point like L, where the interest rate, iL, is below iE. At iL the public wants to hold the quantity of money ML, an amount larger than the actual money supply,  . This means that at point L, the public wants to shift some of its wealth out of interest-

. This means that at point L, the public wants to shift some of its wealth out of interest-

This has two implications. One is that the quantity of money demanded is more than the quantity of money supplied. The other is that the quantity of interest- . That is, the interest rate will rise until it is equal to iE.

. That is, the interest rate will rise until it is equal to iE.

Now consider what happens if the money market is at a point such as H in Figure 15-4, where the interest rate iH is above iE. In that case the quantity of money demanded, MH, is less than the quantity of money supplied,  . Correspondingly, the quantity of interest-

. Correspondingly, the quantity of interest- . Again, the interest rate will end up at iE.

. Again, the interest rate will end up at iE.

Two Models of Interest Rates?

You might have noticed that this is the second time we have discussed the determination of the interest rate. In Chapter 10 we studied the loanable funds model of the interest rate; according to that model, the interest rate is determined by the equalization of the supply of funds from lenders and the demand for funds by borrowers in the market for loanable funds. But here we have described a seemingly different model in which the interest rate is determined by the equalization of the supply and demand for money in the money market. Which of these models is correct?

The answer is both. We explain how the models are consistent with each other in Appendix 15A. For now, let’s put the loanable funds model to one side and concentrate on the liquidity preference model of the interest rate. The most important insight from this model is that it shows us how monetary policy—

Monetary Policy and the Interest Rate

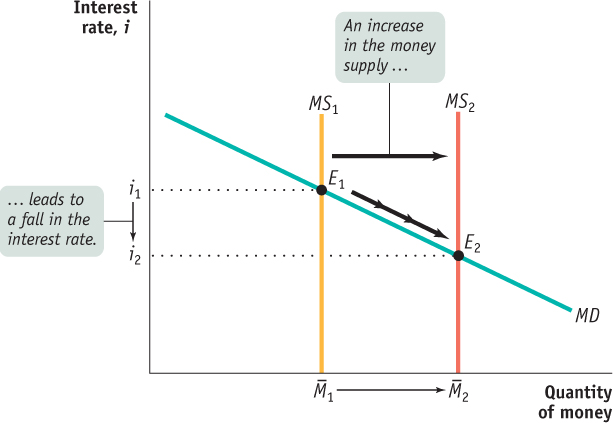

Let’s examine how the Bank of Canada can use changes in the money supply to change the interest rate. Figure 15-5 shows what happens when the BOC increases the money supply from  to

to  . The economy is originally in equilibrium at E1, with an equilibrium interest rate of i1 and money supply

. The economy is originally in equilibrium at E1, with an equilibrium interest rate of i1 and money supply  . An increase in the money supply by the BOC to

. An increase in the money supply by the BOC to  shifts the money supply curve to the right, from MS1 to MS2, and leads to a fall in the equilibrium interest rate to i2. Why? Because i2 is the only interest rate at which the public is willing to hold the quantity of money actually supplied,

shifts the money supply curve to the right, from MS1 to MS2, and leads to a fall in the equilibrium interest rate to i2. Why? Because i2 is the only interest rate at which the public is willing to hold the quantity of money actually supplied,  .

.

to

to  . In order to induce people to hold the larger quantity of money, the interest rate must fall from i1 to i2.

. In order to induce people to hold the larger quantity of money, the interest rate must fall from i1 to i2.So an increase in the money supply drives the interest rate down. Similarly, a reduction in the money supply drives the interest rate up. By adjusting the money supply up or down, the BOC can set the interest rate.

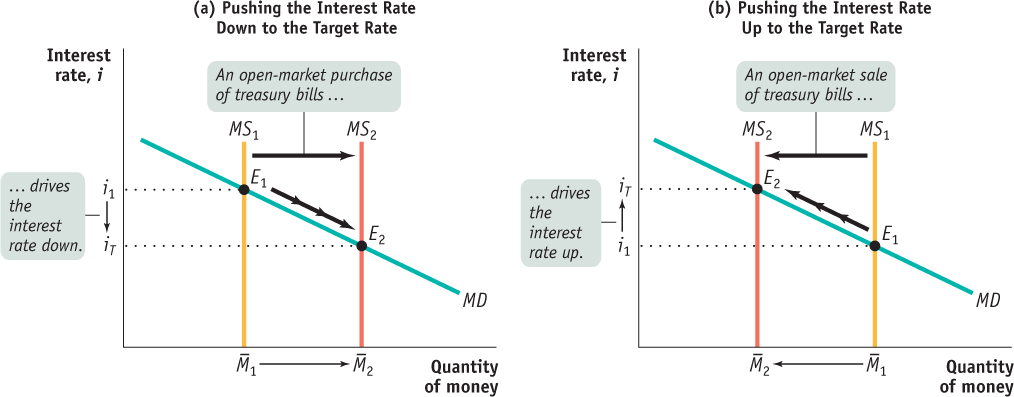

In practice, the Governing Council of the Bank of Canada decides at each meeting what interest rate should prevail until the next fixed announcement date of the target for the overnight rate. The BOC sets a target for the overnight rate, which is the desired level for the overnight rate. The BOC then adjusts the money supply by buying and selling treasury bills until the overnight rate reaches the target rate. The BOC can use other tools to reach the target rate, such as monetary policy implemented via government deposit switching, foreign exchange market intervention, and buying and selling of other assets, but these tools are used only rarely.4

Figure 15-6 shows how this works. In both panels, iT is the target for the overnight rate. In panel (a), the initial money supply curve is MS1 with money supply  , and the equilibrium interest rate, i1, is above the target rate. To lower the interest rate to iT, the BOC makes an open-

, and the equilibrium interest rate, i1, is above the target rate. To lower the interest rate to iT, the BOC makes an open- . This drives the equilibrium interest rate down to the target rate, iT.

. This drives the equilibrium interest rate down to the target rate, iT.

Panel (b) shows the opposite case. Again, the initial money supply curve is MS1 with money supply  . But this time the equilibrium interest rate, i1, is below the overnight rate, iT. In this case, the BOC will make an open-

. But this time the equilibrium interest rate, i1, is below the overnight rate, iT. In this case, the BOC will make an open- via the money multiplier. The money supply curve shifts leftward from MS1 to MS2, driving the equilibrium interest rate up to the target for the overnight rate, iT.

via the money multiplier. The money supply curve shifts leftward from MS1 to MS2, driving the equilibrium interest rate up to the target for the overnight rate, iT.

EIGHT FIXED DATES FOR THE BOC POLICY INTEREST RATE ANNOUNCEMENTS

Eight times a year, in accordance with a pre-

Why is this schedule of announcements important? Because the overnight rate—

In addition, having a schedule of fixed announcement dates ahead of time helps to reduce uncertainty in financial markets and provide transparency for monetary policy. Uncertainty can result in higher interest rates due to investors demanding risk premiums to compensate for additional perceived risk. It also contributes to reluctance on the part of investors to lend and on the part of others to spend and to borrow, and it makes firms wary of hiring additional workers. The consequences are reduced levels of consumption and investment spending, rising unemployment, and shrinking real output. Uncertainty, if high enough, can cause significant economic harm.

It may seem curious that the Bank of Canada commits itself in advance to a schedule of announcements and to changing its key policy interest rate only eight times a year. However, the BOC does have the option of changing the target for the overnight rate between fixed announcement dates in the event of exceptional circumstances. This last occurred in 2008 when, in light of deteriorating economic conditions stemming from the U.S. financial crisis, the BOC lowered the target rate on October 8 (the press release at the beginning of this section), ahead of the scheduled fixed announcement date of October 21, when it again lowered the rate in response to the economic conditions.

The Bank of Canada is not the only central bank to announce its policy interest rate changes on pre-

Long-Term Interest Rates

Earlier in this chapter we mentioned that long-term interest rates—rates on bonds or loans that mature in several years—don’t necessarily move with short-term interest rates. How is that possible, and what does it say about monetary policy?

Consider the case of Millie, who has already decided to place $10 000 in Canadian government bonds for the next two years. However, she hasn’t decided whether to put the money in one-year bonds, at a 4% rate of interest, or two-year bonds, at a 5% rate of interest. If she buys the one-year bond, then in one year, Millie will receive the $10 000 she paid for the bond (the principal) plus interest earned. If instead she buys the two-year bond, Millie will have to wait until the end of the second year to receive her principal and her interest.

THE TARGET VERSUS THE MARKET

Over the years, the Bank of Canada has changed the details of how it makes monetary policy. At one point, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, it did so by setting a target level for the money supply and altering the monetary base to achieve that target. Under this policy, the overnight rate fluctuated freely. However, as of December 2000, the Bank of Canada’s current policy is to do just the opposite: set a target for the overnight rate eight times a year and allow the money supply to fluctuate as it pursues that target.

It is a common mistake to imagine that these policy changes have changed the way the money market works. That is, you’ll sometimes hear people say that the interest rate no longer reflects the supply of and demand for money because the Bank of Canada sets the interest rate.

In fact, the money market works the same way as always: the interest rate is determined by the supply of and demand for money. The only difference is that now the Bank of Canada adjusts the supply of money to achieve its target interest rate. It’s important not to confuse a change in the Bank’s operating procedure with a change in the way the economy works.

You might think that the two-year bonds are a clearly better deal—but they may not be. Suppose that Millie expects the rate of interest on one-year bonds to rise sharply next year. If she puts her funds in one-year bonds this year, she will be able to reinvest the money at a much higher rate next year. And this could give her a two-year rate of return that is higher than if she put her funds into the two-year bonds today. For example, if the rate of interest on one-year bonds rises from 4% this year to 8% next year, putting her funds in a one-year bond today and in another one-year bond a year from now will give her an annual rate of return over the next two years of about 6%, better than the 5% rate on two-year bonds.

The same considerations apply to all investors deciding between short-term and long-term bonds. If they expect short-term interest rates to rise, investors may buy short-term bonds even if long-term bonds bought today offer a higher interest rate today. If they expect short-term interest rates to fall, investors may buy long-term bonds even if short-term bonds bought today offer a higher interest rate today.

As this example suggests, long-term interest rates largely reflect the average expectation in the market about what’s going to happen to short-term rates in the future. When long-term rates are higher than short-term rates, as they were in 2010, the market is signalling that it expects short-term rates to rise in the future.

This is not, however, the whole story: risk is also a factor. Return to the example of Millie, deciding whether to buy one-year or two-year bonds. Suppose that there is some chance she will need to cash in her investment after just one year—say, to meet an emergency medical bill. If she buys two-year bonds, she would have to sell those bonds to meet the unexpected expense. But what price will she get for those bonds? It depends on what has happened to interest rates in the rest of the economy. As we learned in Chapter 10, bond prices and interest rates move in opposite directions: if interest rates rise, bond prices fall, and vice versa.

This means that Millie will face extra risk if she buys two-year rather than one-year bonds, because if a year from now bond prices fall and she must sell her bonds in order to raise cash, she will lose money on the bonds. Owing to this risk factor, long-term interest rates are, on average, higher than short-term rates in order to compensate long-term bond purchasers for the higher risk they face (although this relationship is reversed when short-term rates are unusually high).

As we will see later in this chapter, the fact that long-term rates don’t necessarily move with short-term rates is sometimes an important consideration for monetary policy.

THE BANK OF CANADA REVERSES COURSE

We began this section with the BOC’s press release from October 8, 2008, announcing that it was cutting its target interest rate. This particular action was part of a larger story: a dramatic reversal of the BOC policy that began in December 2007.

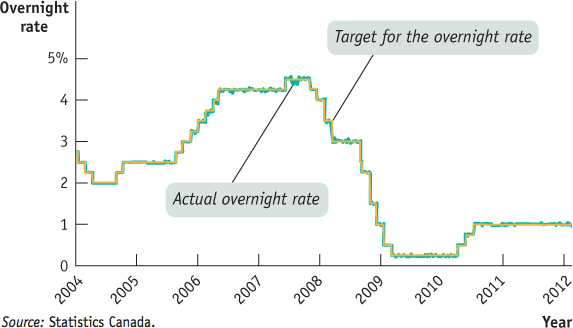

Source: Statistics Canada.

Figure 15-7 shows two interest rates from January 2004 to November 2012: the target for the overnight rate, decided by the BOC, and the actual rate in the overnight money market. As you can see, the BOC raised its target rate in a series of steps from mid-2005 until the middle of 2006; it did this to head off the possibility of an overheating economy and rising inflation (more on that later in this chapter). But the BOC dramatically reversed course beginning in December 2007, as the BOC worried that the weakening of the American economy and the increased tightness in world credit markets might have adverse effects on the Canadian economy. The downward trend in the target for the overnight rate continued until it reached its lowest level in history—0.25% on April 21, 2009. From April 2009 to May 2010, the target for the overnight rate was kept at 0.25% in response to a weak economy and high unemployment.

Figure 15-7 also shows that the BOC usually hits its target—the actual and the target for the overnight rates are often very similar. But not always: the BOC missed its target on numerous days in 2007, especially when the actual overnight rate was above or below the target rate. However, these episodes did not last long, and overall the BOC got what it wanted, at least as far as short-term interest rates were concerned.

Quick Review

According to the liquidity preference model of the interest rate, the equilibrium interest rate is determined by the money demand curve and the money supply curve.

The Bank of Canada can move the interest rate through open-market operations that shift the money supply curve. In practice, the BOC sets the target for the overnight rate and uses open-market operations to achieve that target.

Long-term interest rates reflect expectations about what’s going to happen to short-term rates in the future. Because of risk, long-term interest rates tend to be higher than short-term rates.

Check Your Understanding 15-2

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 15-2

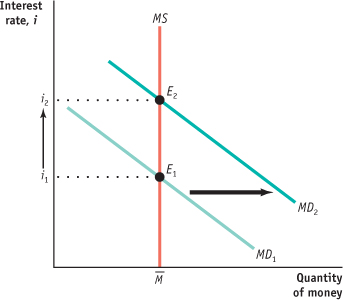

Assume that there is an increase in the demand for money at every interest rate. Using a diagram, show what effect this will have on the equilibrium interest rate for a given money supply.

In the accompanying diagram, the increase in the demand for money is shown as a rightward shift of the money demand curve, from MD1 to MD2. This raises the equilibrium interest rate from i1 to i2.

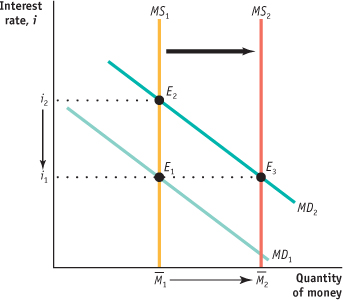

Now assume that the Bank of Canada is following a policy of targeting the overnight rate. What will the BOC do in the situation described in Question 1 to keep the overnight rate unchanged? Illustrate with a diagram.

In order to prevent the interest rate from rising, the Bank of Canada must make an open-market purchase of Treasury bills, shifting the money supply curve rightward. This is shown in the accompanying diagram as the move from MS1 to MS2.

Frannie must decide whether to buy a one-year bond today and another one a year from now, or buy a two-year bond today. In which of the following scenarios is she better off taking the first action? The second action?

This year, the interest rate on a one-year bond is 4%; next year, it will be 10%. The interest rate on a two-year bond is 5%.

This year, the interest rate on a one-year bond is 4%; next year, it will be 1%. The interest rate on a two-year bond is 3%.

Frannie is better off buying a one-year bond today and a one-year bond tomorrow because this allows her to get the higher interest rate one year from now.

Frannie is better off buying a two-year bond today because it gives her a higher interest rate in the second year than if she bought two one-year bonds.