17.2 Banking Crises and Financial Panics

A banking crisis occurs when a large part of the depository banking sector or the shadow banking sector fails or threatens to fail.

While rare in Canada, bank failures are common in some other countries. Even in a good year, several U.S. banks typically go under for one reason or another. And shadow banks sometimes fail, too. Banking crises—episodes in which a large part of the depository banking sector or the shadow banking sector fails or threatens to fail—

The Logic of Banking Crises

When many banks—

In an asset bubble, the price of an asset is pushed to an unreasonably high level due to expectations of further price gains.

Shared Mistakes In practice, banking crises usually owe their origins to many banks making the same mistake of investing in an asset bubble. In an asset bubble, the price of some kind of asset, such as housing, is pushed to an unreasonably high level by investors’ expectations of further price gains. For a while, such bubbles can feed on themselves. A good example is the U.S. savings and loan crisis of the 1980s, when there was a huge boom in the construction of commercial real estate, especially office buildings. Many banks extended large loans to real estate developers, believing that the boom would continue indefinitely. By the late 1980s, it became clear that developers had gotten carried away, building far more office space than the country needed. Unable to rent out their space or forced to slash rents, a number of developers, including the Canadian company Olympia & York, which had grown to one of the largest commercial property development firms in the world, defaulted on their loans—

A similar phenomenon occurred between 2002 and 2006, in the U.S., when rapidly rising housing prices led many people to borrow heavily to buy a house in the belief that prices would keep rising. This process accelerated as more buyers rushed into the market and pushed housing prices up even faster. Eventually the market runs out of new buyers and the bubble bursts. At this point asset prices fall; in some parts of the United States, housing prices fell by half between 2006 and 2009. This, in turn, undermines confidence in financial institutions that are exposed to losses due to falling asset prices. This loss of confidence, if it’s sufficiently severe, can set in motion the kind of economy-

Thankfully, no Canadian-

Recently, economists have begun to worry about the level of household debt in Canada. In the third quarter of 2012, Statistics Canada reported that Canadian household debt had grown to a record high of 165 percent of disposable income, about the same level reached in the United States before the 2008–2009 financial crisis. This fact, coupled with estimates of slowing Canadian economic growth, led Standard & Poor’s (S&P) and Moody’s to downgrade the credit ratings for several of Canada’s leading banks in late 2012 and early in 2013. “High levels of consumer indebtedness and elevated housing prices leave Canadian banks more vulnerable than in the past to downside risks the Canadian economy faces,” said David Beattie, a Moody’s vice-

A financial contagion is a vicious downward spiral among depository banks or shadow banks: each bank’s failure worsens fears and increases the likelihood that another bankwill fail.

Financial Contagion In especially severe banking crises, a vicious downward spiral of financial contagion occurs among depository banks or shadow banks: each institution’s failure worsens depositors’ or lenders’ fears and increases the odds that another bank will fail.

As already noted, one underlying cause of contagion arises from the logic of bank runs. In the case of depository banks, when one bank fails, depositors are likely to become nervous about others. Similarly in the case of shadow banks, when one fails, lenders in the short-

There is also a second channel of contagion: asset markets and the vicious cycle of deleveraging, a phenomenon we learned about in Chapter 14. When a financial institution is under pressure to reduce debt and raise cash, it tries to sell assets. To sell assets quickly, though, it often has to sell them at a deep discount. The contagion comes from the fact that other financial institutions own similar assets, whose prices decline as a result of the “fire sale.” This decline in asset prices hurts the other financial institutions’ financial positions, too, leading their creditors to stop lending to them—

A financial panic is a sudden and widespread disruption of the financial markets that occurs when people suddenly lose faith in the liquidity of financial institutionsand markets.

Combine an asset bubble with a huge, unregulated shadow banking system and a vicious cycle of deleveraging and it is easy to see, as the U.S. economy did in 2008, how a full-

Because banking provides much of the liquidity needed for trading financial assets like stocks and bonds, severe banking crises almost always lead to disruptions of the stock and bond markets. Disruptions of these markets, along with a headlong rush to sell assets and raise cash, lead to a vicious circle of deleveraging. As the panic unfolds, the resulting high levels of fear and uncertainty make savers and investors come to believe that the safest place for their money is under their bed, and their hoarding of cash further deepens the distress.

So what can history tell us about banking crises and financial panics?

Historical Banking Crises: The Age of Panics

Between the American Civil War and the Great Depression, the United States had a famously crisis-

Table 17-1 shows the dates of these nationwide American banking crises and the number of banks that failed in each episode. Notice that the table is divided into two parts. The first part is devoted to the “national banking era,” which preceded the 1913 creation of the U.S. Federal Reserve—

The events that sparked each of these panics differed. In the nineteenth century, there was a boom-

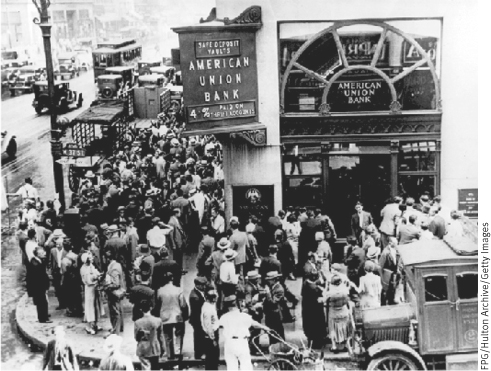

As we’ll see later in this chapter, the major financial panics of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were followed by severe economic downturns in the United States. However, the banking crises of the early 1930s made previous crises seem minor by comparison. In four successive waves of bank runs from 1930 to 1932, about 40% of the banks in America failed. In the end, U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt declared a temporary closure of all banks—

There is still considerable controversy about the U.S. banking crisis of the early 1930s. In part, this controversy is about cause and effect: did the banking crisis cause the wider economic crisis, or vice versa? (No doubt causation ran in both directions, but the magnitude of these effects remains disputed.) There is also controversy about the extent to which the banking crisis could have been avoided. Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz, in their famous study Monetary History of the United States, argued that the Federal Reserve could and should have prevented the banking crisis—

In the United States, the experience of the 1930s led to banking reforms that prevented a replay for more than 70 years. Outside the United States, however, there were a number of major banking crises.

Modern Banking Crises Around the World

Around the world, banking crises are relatively frequent events. However, the ways in which they occur differ according to the banking sector’s particular institutional framework. According to a 2008 analysis by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), no fewer than 127 banking crises occurred around the world between 1970 and 2007. Most of these were in small, poor countries that lack the regulatory safeguards found in advanced countries. In poorer countries, banks generally get in trouble in much the same way: insufficient capital, poor accounting, too many loans, and, often, corruption. But banks in advanced countries can also make the same mistakes—for example, there was the savings and loan crisis in the United States during the 1980s (mentioned earlier in this chapter).

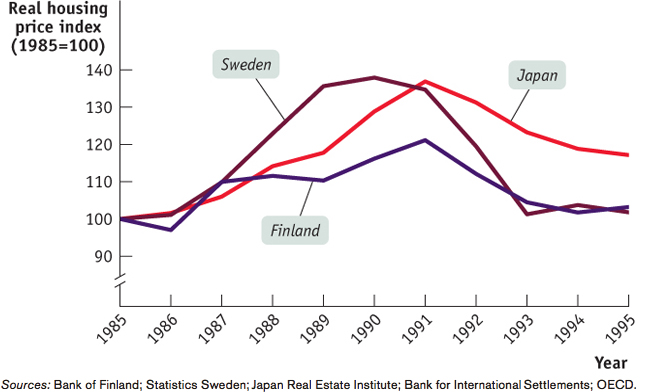

In more advanced countries, banking crises almost always occur as a consequence of an asset bubble—typically in real estate. Between 1985 and 1995, three advanced countries—Finland, Sweden, and Japan—experienced banking crises due to the bursting of a real estate bubble. Banks in the three countries lent heavily into a real estate bubble that their lending helped to inflate. Figure 17-1 shows real estate prices, adjusted for inflation, in Finland, Sweden, and Japan from 1985 to 1995. As you can see, in each country a sharp rise was followed by a drastic fall, leading many borrowers to default on their real estate loans, pushing large parts of each country’s banking system into insolvency. The Teranet–National Bank Home Price Index (HPI) reveals that the real price of homes in Canada rose by 74% between January 2000 and the end of 2012. This increase in price occurred over a longer time period than similar increases in countries that experienced real estate bubbles. Nonetheless, the magnitude of this increase, along with the fact that home prices grew much more quickly than disposable income over this time span, has caused some to wonder whether Canadian home prices are in bubble territory. And even the possibility of a Canadian residential real estate bubble significantly increases the likelihood of a banking crisis.

For many years, Bear Stearns had been a respected and successful financial securities firm based in the United States. But in March 2008 investors began to lose confidence in Bear Stearns’ ability to repay its debts, resulting in a liquidity crisis for the company. Unable to obtain the capital it needed, Bear Stearns failed. Thanks to a $29 billion government bailout, JPMorgan Chase, a large American bank, was able to take over Bear Stearns. Unfortunately, fear and uncertainty remained in American financial markets. The fall of Lehman in September 2008 precipitated a banking crisis in the shadow banking sector that included financial contagion as well as financial panic, but left the depository banking sector largely unaffected. As we discussed in the opening story, the financial crisis of 2008 was devastating because of securitization, which had distributed sub-prime mortgage loans throughout the entire shadow banking sector throughout the world, especially in the United States.

At the time of writing, the market for securitization has not yet recovered and the shadow banking sector is a shadow of its former self. Since 2008, investors have rediscovered the benefits of regulation, and the depository banking sector has grown at the expense of the shadow banking sector. In the next section, we will learn how troubles in the banking sector soon translate into troubles for the broader economy.

ERIN GO BROKE

For much of the 1990s and 2000s, Ireland was celebrated as an economic success story: the “Celtic Tiger” was growing at a pace the rest of Europe could only envy. But the miracle came to an abrupt halt in 2008, as Ireland found itself facing a huge banking crisis.

Like the earlier banking crises in Finland, Sweden, and Japan, Ireland’s crisis grew out of excessive optimism about real estate. Irish housing prices began rising in the 1990s, in part a result of the economy’s strong growth. However, real estate developers began betting on ever-rising prices, and Irish banks were all too willing to lend these developers large amounts of money to back their speculations. Housing prices tripled between 1997 and 2007, home construction quadrupled over the same period, and total credit offered by banks rose far faster than in any other European nation. To raise the cash for their lending spree, Irish banks supplemented the funds of depositors with large amounts of “wholesale” funding—short-term borrowing from other banks and private investors.

In 2007 the real estate boom collapsed. Home prices started falling, and home sales collapsed. Many of the loans that banks had made during the boom went into default. Now, so-called ghost estates, new housing developments full of unoccupied, crumbling homes, dot the landscape. In 2008, the troubles of the Irish banks threatened to turn into a sort of bank run—not by depositors, but by lenders who had provided the banks with short-term funding through the wholesale interbank lending market. To stabilize the situation, the Irish government stepped in, guaranteeing repayment of all bank debt.

This created a new problem because it put Irish taxpayers on the hook for potentially huge bank losses. Until the crisis struck, Ireland had seemed to be in good fiscal shape, with relatively low government debt and a budget surplus. The banking crisis, however, led to serious questions about the solvency of the Irish government—whether it had the resources to meet its obligations—and forced the government to pay high interest rates on funds it raised in international markets.

Like most banking crises, Ireland’s led to a severe recession. The unemployment rate rose from less than 5% before the crisis, peaking at 15.1% early in 2012 before declining below 15% later in the year.

Quick Review

Although individual bank failures are common in some countries (but not in Canada), a banking crisis is a rare event that typically will severely harm the broader economy.

A banking crisis can occur because depository or shadow banks invest in an asset bubble or through financial contagion, set off by bank runs or by a vicious cycle of deleveraging. Largely unregulated, the shadow banking sector is particularly vulnerable to contagion.

In 2008, an asset bubble combined with a huge shadow banking sector and a vicious cycle of deleveraging created a financial panic and banking crisis in the United States, as savers cut their spending and investors hoarded their funds, sending the economy into a steep decline.

Between the American Civil War and the Great Depression, the United States suffered numerous banking crises and financial panics, each followed by a severe economic downturn. The banking reforms of the 1930s prevented another banking crisis until 2008.

Banking crises usually occur in small, poor countries, although there have been banking crises in rich countries as well. In 2008, the fall of Lehman caused a U.S. banking crisis and a worldwide financial panic in the shadow banking sector, leading investors to shift back into the depository banking sector.

Check Your Understanding 17-2

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 17-2

Regarding the Economics in Action “Erin Go Broke,” identify the following:

The asset bubble

The channel of financial contagion

The asset bubble occurred in Irish real estate.

The channel of the financial contagion was the short-term lending that Irish banks depended on from the wholesale interbank lending market. When lenders began to worry about the soundness of the Irish banks, they refused to lend any more money, leading to a type of bank run and putting the Irish banks at great risk of failure.

Again regarding “Erin Go Broke,” why do you think the Irish government tried to stabilize the situation by guaranteeing the debts of the banks? Why was this a questionable policy?

Because the bank run started with fears among lenders to Irish banks, the Irish government sought to eliminate those fears by guaranteeing the lenders that they would be repaid in full. It was a questionable strategy, though, because it put the Irish taxpayers on the hook for potentially very large losses, so large that they threatened the solvency of the Irish government.