18.1 Classical Macroeconomics

The term macroeconomics appears to have been coined in 1933 by the Norwegian economist Ragnar Frisch. The date, during the worst year of the Great Depression, is no accident. Still, there were economists analyzing what we now consider macroeconomic issues—

Money and the Price Level

In Chapter 16, we described the classical model of the price level. According to the classical model, prices are flexible, making the aggregate supply curve vertical even in the short run.1 In this model, an increase in the money supply leads, other things equal, to an equal proportional rise in the aggregate price level, with no effect on aggregate output. As a result, increases in the money supply lead to inflation, and that’s all. Before the 1930s, the classical model of the price level dominated economic thinking about the effects of monetary policy.

Did classical economists really believe that changes in the money supply affected only aggregate prices, without any effect on aggregate output? Probably not. Historians of economic thought argue that before 1930 most economists were aware that changes in the money supply affect aggregate output as well as aggregate prices in the short run—

The Business Cycle

Classical economists were, of course, also aware that the economy did not grow smoothly. The American economist Wesley Mitchell pioneered the quantitative study of business cycles. In 1920 he founded the National Bureau of Economic Research, an independent, non-

In the absence of any clear theory, conflicts arose among policy-

Necessity was, however, the mother of invention. As we’ll explain next, the Great Depression provided a strong incentive for economists to develop theories that could serve as a guide to policy—

WHEN DID THE BUSINESS CYCLE BEGIN?

The modern business cycle probably originated in Britain—

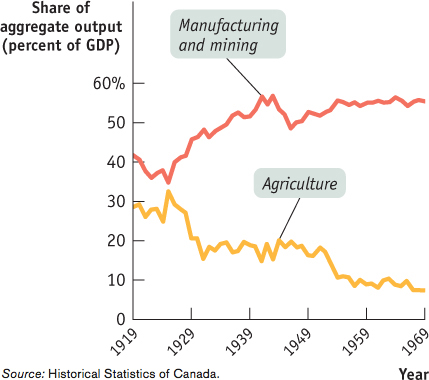

But when did Canada have its first business cycle? Unfortunately, we can’t know for sure. There are two reasons for this. The first reason is that the further back in time we go, the less economic data are available. We have GDP data only from 1926 and output by industry from 1919. The other is that business cycles, in the modern sense, depend upon having a predominantly industrial society. We know that Canada had an overwhelmingly rural, agricultural economy throughout most of the 1800s. But by 1919—the first year for which we have data—

But why does the modern business cycle depend on having a predominantly industrialized society? Fluctuations in aggregate output in agricultural economies are very different from the business cycles we know today. That’s because the prices of agricultural goods tend to be highly flexible. As a result, the short-

Quick Review

Classical macroeconomists focused on the long-

run effects of monetary policy on the aggregate price level, ignoring any short- run effects on aggregate output. By the time of the Great Depression, the measurement of business cycles was well advanced, but there was no widely accepted theory about why they happened.

Check Your Understanding 18-1

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 18-1

When Ben Bernanke, in his tribute to Milton Friedman, said that “Regarding the Great Depression … we did it,” he was referring to the fact that the U.S. Federal Reserve at the time did not pursue expansionary monetary policy. Why would a classical economist have thought that action by the Federal Reserve would not have made a difference in the length or depth of the Great Depression?

A classical economist would have said that although expansionary monetary policy would probably have some effect in the short run, the short run was unimportant. Instead, a classical economist would have stressed the long run, claiming expansionary monetary policy would result only in an increase in the aggregate price level without affecting aggregate output.