18.2 The Great Depression and the Keynesian Revolution

The Great Depression demonstrated, once and for all, that economists cannot safely ignore the short run. Not only was the economic pain severe; it threatened to destabilize societies and political systems. In particular, the economic plunge helped Adolf Hitler rise to power in Germany.

The whole world wanted to know how this economic disaster could be happening and what should be done about it. But because there was no widely accepted theory of the business cycle, economists gave conflicting and, we now believe, often harmful advice. Some believed that only a huge change in the economic system—

Some economists, however, argued that the slump both could and should be cured—

Nice metaphor. But what was the nature of the trouble?

Keynes’s Theory

In 1936 Keynes presented his analysis of the Great Depression—

As Samuelson’s description suggests, Keynes’s book is a vast stew of ideas. Keynesian economics is principally based on two innovations. First, Keynes emphasized the short-

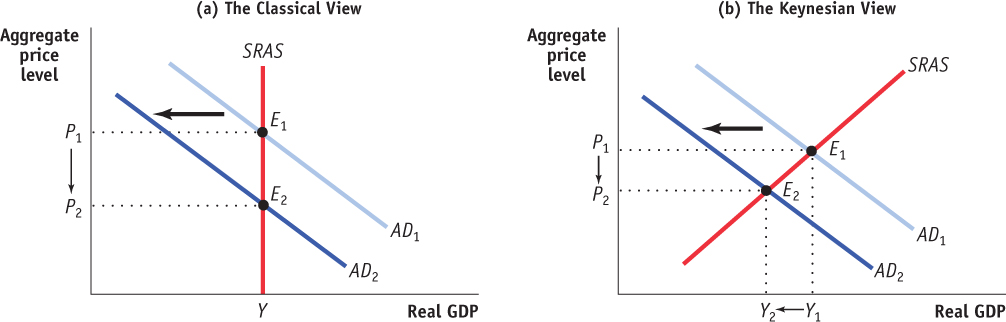

Figure 18-2 illustrates the difference between Keynesian and classical macroeconomics. Both panels of the figure show the short-

Panel (a) shows the classical view: the short-

As we’ve already explained, many classical macroeconomists would have agreed that panel (b) was an accurate story in the short run—

Classical economists emphasized the role of changes in the money supply in shifting the aggregate demand curve, paying little attention to other factors. Keynes’s second innovation was his argument that other factors, especially changes in “animal spirits”—these days usually referred to with the bland term business confidence—are mainly responsible for business cycles. Before Keynes, economists often argued that a decline in business confidence would have no effect on either the aggregate price level or aggregate output, as long as the money supply stayed constant. Keynes offered a very different picture.

Keynesian economics rests on two main tenets: changes in aggregate demand affect aggregate output, employment, and prices; and changes in business confidence cause the business cycle.

Keynesian economics has penetrated deeply into the public consciousness, to the extent that many people who have never heard of Keynes, or have heard of him but think they disagree with his theory, use Keynesian ideas all the time. For example, suppose that a business commentator says something like this: “Because of a decline in business confidence, investment spending slumped, causing a recession.” Whether the commentator knows it or not, that statement is pure Keynesian economics.

THE POLITICS OF KEYNES

The term Keynesian economics is sometimes used as a synonym for left-

As we explain in the text, Keynesian ideas have actually been accepted across a broad range of the political spectrum. In 2004 the American president was a conservative, as was his top economist, N. Gregory Mankiw; but Mankiw is also the editor of a collection of readings titled New Keynesian Economics.

And Keynes himself was no socialist—

What is true is that the rise of Keynesian economics in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s went along with a general enlargement of the role of government in the economy, and those who favoured a larger role for government tended to be enthusiastic Keynesians. Conversely, a swing of the pendulum back toward free-

Keynes himself more or less predicted that his ideas would become part of what “everyone knows.” In another famous passage, this from the end of The General Theory, he wrote: “Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.”

Policy to Fight Recessions

Macroeconomic policy activism is the use of monetary and fiscal policy to smooth out the business cycle.

The main practical consequence of Keynes’s work was that it legitimized macroeconomic policy activism—the use of monetary and fiscal policy to smooth out the business cycle.

Macroeconomic policy activism wasn’t something completely new. Before Keynes, many economists had argued for using monetary expansion to fight economic downturns—

However, these efforts were half-

After World War II, Keynesian ideas were broadly accepted by economists. There were, however, a series of challenges to those ideas, which led to a considerable shift in views even among those economists who continued to believe that Keynes was broadly right about the causes of recessions. In the upcoming section, we’ll learn about those challenges and the schools, new classical economics and new Keynesian economics, that emerged.

THE END OF THE GREAT DEPRESSION

It would make a good story if Keynes’s ideas had led to a change in economic policy that brought the Great Depression to an end. Unfortunately, that’s not what happened. Still, the way the Depression ended did a lot to convince economists that Keynes was right.

The basic message many of the young economists who adopted Keynes’s ideas in the 1930s took from his work was that economic recovery requires aggressive fiscal expansion—

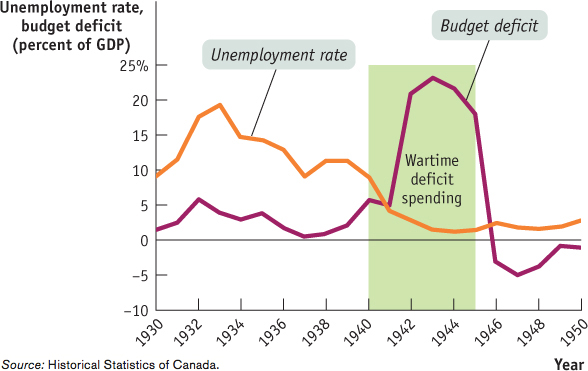

Figure 18-3 shows the Canadian unemployment rate and the federal budget deficit as a percentage of GDP from 1930 to 1950. As you can see, during the 1930s, deficit spending occurred on a very modest scale. It was only after Canada entered World War II in 1939 that federal deficit spending really began to increase—

And the economy recovered. World War II wasn’t intended as a Keynesian fiscal policy, but it demonstrated that expansionary fiscal policy can, in fact, create jobs in the short run.

Quick Review

The key innovations of Keynesian economics are an emphasis on the short run, in which the SRAS curve slopes upward rather than being vertical, and the belief that changes in business confidence shift the AD curve and thereby generate business cycles.

Keynesian economics provided a rationale for macroeconomic policy activism.

Keynesian ideas are widely used even by people who haven’t heard of Keynes or think they disagree with him.

Check Your Understanding 18-2

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 18-2

The Canadian Federation of Independent Business (CFIB) calculates an index of business confidence known as the Business Barometer. In February 2013, the CFIB stated, “After a lacklustre November and December, Canadian entrepreneurs are feeling more optimistic in early 2013 … The Business Barometer index continued January’s upward trend by rising another half a point to 66.2 in February.” Ted Mallett, CFIB’s chief economist and vice-

president reported, “For the first time in a while, small business owners are reporting index numbers that indicate the economy is growing nearer its potential. The January and February results suggest Canadians are seeing modest, but widespread economic growth.” Do these statements support Keynesian theory? Which conclusion would a Keynesian economist draw for the need for public policy?

The statements support Keynesian theory. According to Keynes, business confidence (which he called “animal spirits”) is mainly responsible for recessions. If business confidence is rising, a Keynesian economist would think that investment would rise and aggregate demand would shift to the right. As the economy is recovering from a recession, a Keynesian economist would think of this as a case for macroeconomic policy activism: that the government should use expansionary monetary and fiscal policy to help the economy reaches its potential output faster (i.e., to speed up the recovery).