18.3 Challenges to Keynesian Economics

Keynes’s ideas fundamentally changed the way economists think about business cycles. They did not, however, go unquestioned. In the decades that followed the publication of The General Theory, Keynesian economics faced a series of challenges. As a result, the consensus of macroeconomists retreated somewhat from the strong version of Keynesianism that prevailed in the 1950s. In particular, economists became much more aware of the limits to macroeconomic policy activism.

The Revival of Monetary Policy

Keynes’s The General Theory suggested that monetary policy wouldn’t be very effective in depression conditions. Many modern macroeconomists agree: in Chapter 16 we introduced the concept of a liquidity trap, a situation in which monetary policy is ineffective because the interest rate is down against the zero bound. In the 1930s, when Keynes wrote, interest rates were, in fact, very close to 0%. (The term liquidity trap was first introduced by the British economist John Hicks in a 1937 paper, “Mr. Keynes and The Classics: A Suggested Interpretation,” that summarized Keynes’s ideas.)

But even when the era of near-

The revival of interest in monetary policy was significant because it suggested that the burden of managing the economy could be shifted away from fiscal policy—

Monetary policy, in contrast, does not involve such choices: when the central bank cuts interest rates to fight a recession, it cuts everyone’s interest rate at the same time. So a shift from relying on fiscal policy to relying on monetary policy makes macroeconomics a more technical, less political issue. In fact, as we learned in Chapter 14, monetary policy in most major economies is set by an independent central bank that is insulated from the political process.

Monetarism

Monetarism asserts that GDP will grow steadily if the money supply grows steadily.

After the publication of A Monetary History, Milton Friedman led a movement that sought to eliminate macroeconomic policy activism while maintaining the importance of monetary policy. Monetarism asserts that GDP will grow steadily if the money supply grows steadily. The monetarist policy prescription was to have the central bank target a constant rate of growth of the money supply, such as 3% per year, and maintain that target regardless of any fluctuations in the economy.

It’s important to realize that monetarism retained many Keynesian ideas. Like Keynes, Friedman asserted that the short run is important and that short-

Discretionary monetary policy is the use of changes in the interest rate or the money supply to stabilize the economy.

Monetarists argued, however, that most of the efforts of policy-

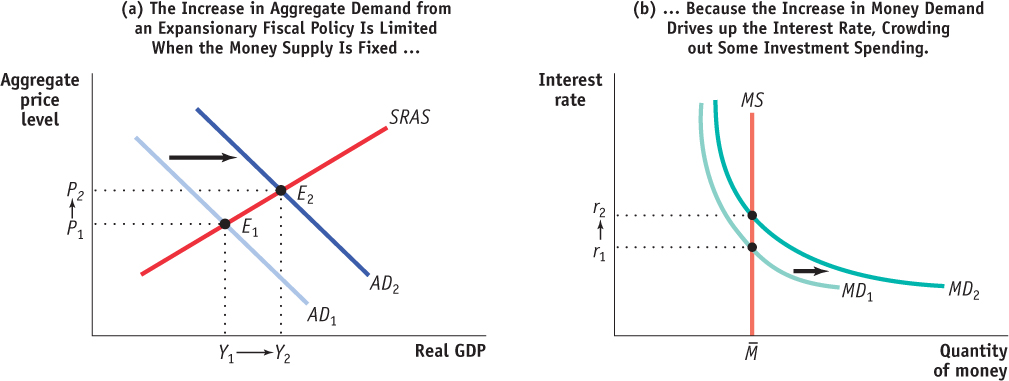

Friedman also argued that if the central bank followed his advice and refused to change the money supply in response to fluctuations in the economy, fiscal policy would be much less effective than Keynesians believed. In Chapter 10 we analyzed the phenomenon of crowding out, in which government deficits drive up interest rates and lead to reduced investment spending. Friedman and others pointed out that if the money supply is held fixed while the government pursues an expansionary fiscal policy, crowding out will occur and will limit the effect of the fiscal expansion on aggregate demand.

Figure 18-4 illustrates this argument. Panel (a) shows aggregate output and the aggregate price level. AD1 is the initial aggregate demand curve and SRAS is the shortrun aggregate supply curve. At the initial equilibrium, E1, the level of aggregate output is Y1 and the aggregate price level is P1. Panel (b) shows the money market. MS is the money supply curve and MD1 is the initial money demand curve, so the initial interest rate is r1.

Now suppose the government increases purchases of goods and services. We know that this will shift the AD curve rightward, as illustrated by the shift from AD1 to AD2, and that aggregate output will rise, from Y1 to Y2 and the aggregate price level will rise, from P1 to P2. Both the rise in aggregate output and the rise in the aggregate price level will, however, increase the demand for money, shifting the money demand curve rightward from MD1 to MD2. This drives up the equilibrium interest rate to r2. Friedman’s point was that this rise in the interest rate reduces investment spending, partially offsetting the initial rise in government spending. As a result, the rightward shift of the AD curve is smaller than the multiplier analysis in Chapter 13 indicated. And Friedman argued that with a constant money supply, the multiplier is so small that there’s not much point in using fiscal policy, even in a depressed economy.

But Friedman didn’t favour activist monetary policy either. He argued that the problems of time lags that limit the ability of discretionary fiscal policy to stabilize the economy also apply to discretionary monetary policy. Friedman’s solution was to put monetary policy on “autopilot.” The central bank, he argued, should follow a monetary policy rule, a formula that determines its actions and leaves it relatively little discretion. During the 1960s and 1970s, most monetarists favoured a monetary policy rule of slow, steady growth in the money supply. Underlying this view was the concept of the velocity of money, the ratio of nominal GDP to the money supply. Velocity is a measure of the number of times the average dollar bill in the economy turns over per year between buyers and sellers (e.g., I tip the Starbucks barista a dollar, she uses it to buy lunch, and so on). This concept gives rise to the velocity equation:

A monetary policy rule is a formula that determines the central bank’s actions.

The velocity of money is the ratio of nominal GDP to the money supply.

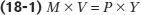

where M is the money supply, V is velocity, P is the aggregate price level, and Y is real GDP.

Monetarists believed, with considerable historical justification, that the velocity of money was stable in the short run and changes only slowly in the long run. As a result, they claimed, steady growth in the money supply by the central bank would ensure steady growth in spending, and therefore in GDP.

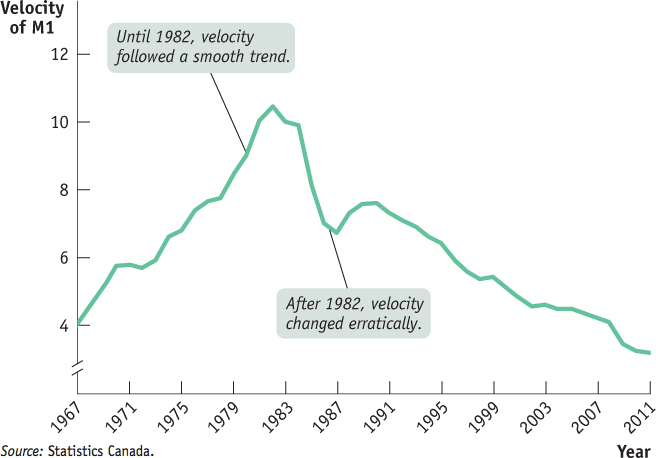

Monetarism strongly influenced actual monetary policy in the late 1970s and early 1980s. It quickly became clear, however, that steady growth in the money supply didn’t ensure steady growth in the economy: the velocity of money wasn’t stable enough for such a simple policy rule to work. Figure 18-5 shows how events eventually undermined the monetarists’ view. The figure shows the velocity of money, as measured by the ratio of nominal GDP to M1, from 1967 to 2011. As you can see, until 1982, velocity followed a fairly smooth, seemingly predictable trend. After the Bank of Canada began to adopt monetarist ideas in the late 1970s and early 1980s, however, the velocity of money began moving erratically—

Traditional monetarists—

Inflation and the Natural Rate of Unemployment

At the same time that monetarists were challenging Keynesian views about how macroeconomic policy should be conducted, other economists—

In the 1940s and 1950s, many Keynesian economists believed that expansionary fiscal policy could be used to achieve full employment on a permanent basis. In the 1960s, however, many economists realized that expansionary policies could cause problems with inflation, but they still believed policy-

According to the natural rate hypothesis, because inflation is eventually embedded into expectations, to avoid accelerating inflation over time the unemployment rate must be high enough that the actual inflation rate equals the expected inflation rate.

In 1968, however, Milton Friedman and Edmund Phelps of Columbia University, working independently, proposed the concept of the natural rate of unemployment, which we discussed in Chapter 8. And in Chapter 16 we showed that the natural rate of unemployment is also the non-

The natural rate hypothesis limits the role of activist macroeconomic policy compared to earlier theories. Because the government can’t keep unemployment below the natural rate, its task is not to keep unemployment low but to keep it stable—to prevent large fluctuations in unemployment in either direction.

The Friedman–

The Political Business Cycle

One final challenge to Keynesian economics focused not on the validity of the economic analysis but on its political consequences. A number of economists and political scientists pointed out that activist macroeconomic policy lends itself to political manipulation.

Statistical evidence suggests that election results tend to be determined by the state of the economy in the months just before the election. For example, in the United States, if the economy is growing rapidly and the unemployment rate is falling in the six months or so before Election Day, the incumbent party tends to be re-elected even if the economy performed poorly in the preceding three years.

This creates an obvious temptation to abuse activist macroeconomic policy: pump up the economy in an election year, and pay the price in higher inflation and/or higher unemployment later. The result can be unnecessary instability in the economy, a political business cycle caused by the use of macroeconomic policy to serve political ends.

A political business cycle results when politicians use macroeconomic policy to serve political ends.

An often-cited example is the combination of expansionary fiscal and monetary policy that led to rapid growth in the U.S. economy just before the 1972 election and a sharp acceleration in inflation after the election. Kenneth Rogoff, a highly respected macroeconomist who served as chief economist at the International Monetary Fund, has proclaimed Richard Nixon, the president at the time, “the all-time hero of political business cycles.”

As we learned in Chapter 14, one way to avoid a political business cycle is to place monetary policy in the hands of an independent central bank, insulated from political pressure. The political business cycle is also a reason to limit the use of discretionary fiscal policy to extreme circumstances.

THE BANK OF CANADA’S FLIRTATION WITH MONETARISM

Between 1975 and 1982, the Bank of Canada flirted with monetarism. Previously, the Bank had mainly targeted interest rates, adjusting its target based on the state of the economy. In 1975, however, the Bank began announcing target ranges for several measures of the money supply. It also stopped setting targets for interest rates. Most people saw these changes as a strong move toward monetarism.

In November 1982, however, the Bank of Canada announced that “the recorded M1 series is not a useful guide to policy at this time. In these circumstances the Bank no longer has a target for it.” In effect, at that point the Bank turned its back on monetarism. After 1982, the Bank went back to using interest rates as its primary policy instrument. And since 1991, movements in interest rates have been determined by the goal of keeping inflation within its target bounds. If you visit the Bank of Canada’s website today, you can find statements bluntly declaring that “the Bank of Canada can’t directly increase or decrease the money supply at will.”

Why did the Bank flirt with monetarism, and then give it up? The turn to monetarism largely reflected the events of the 1970s, when a sharp rise in inflation had the effect of discrediting traditional economic policies. Also, the fact that the natural rate hypothesis had successfully predicted a worsening of the trade-off between unemployment and inflation increased the prestige of Milton Friedman and his intellectual followers. So policy-makers were willing to try Friedman’s policy proposals.

The turn away from monetarism also reflected events: as we saw in Figure 18-5, the velocity of money, which had followed a smooth trend before 1982, became erratic after 1982. This made monetarism seem like a much less good idea.

Quick Review

Early Keynesianism downplayed the effectiveness of monetary as opposed to fiscal policy, but later macroeconomists realized that monetary policy is effective except in the case of a liquidity trap.

According to monetarism, discretionary monetary policy does more harm than good and a simple monetary policy rule is the best way to stabilize the economy. Monetarists believe that the velocity of money was stable and therefore steady growth of the money supply would lead to steady growth of GDP. This doctrine was popular for a time but has receded in influence.

The natural rate hypothesis, now very widely accepted, places sharp limits on what macroeconomic policy can achieve.

Concerns about a political business cycle suggest that the central bank should be independent and that discretionary fiscal policy should be avoided except in extreme circumstances like a liquidity trap.

Check Your Understanding 18-3

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 18-3

Consider Figure 18-5.

If the Bank of Canada had pursued a monetarist policy of a constant rate of growth in the money supply, what would have happened to output at the end of 2008 according to the velocity equation?

In fact, the Bank of Canada accelerated the rate of growth in M1 rapidly at the end of 2008, partly in order to counteract a large increase in unemployment. Would a monetarist have agreed with this policy? What limits are there, according to a monetarist point of view, to changing the unemployment rate?

According to the velocity equation, M × V = P × Y, where M is the money supply, V the velocity of money, P the aggregate price level, and Y real GDP. If the Bank of Canada had pursued a monetary policy rule of constant money supply growth, the decline in the velocity of money at the end of 2008 and visible in Figure 18-5 would have resulted in a dramatic decline in aggregate output.

Although monetarists generally believe that monetary policy is not only effective but, in fact, more effective than fiscal policy, they also generally do not favour macroeconomic policy activism. Instead, monetarists generally advocate monetary policy rules, such as a low but constant rate of money supply growth. In addition, the natural rate hypothesis states that although monetary policy may be effective in helping return unemployment to its natural rate, it cannot permanently reduce unemployment below the natural rate.

What are the limits of macroeconomic policy activism?

Fiscal policy is limited by time lags in recognizing economic problems, forming a response, passing legislation, and implementing the policies. Monetary policy is also limited by time lags, but these lags are not as severe as those for fiscal policy because the Bank of Canada tends to act more quickly than the Parliament. Attempts to reduce unemployment below the natural rate via both fiscal and monetary policy are limited by predictions of the natural rate hypothesis: that these attempts will result in accelerating inflation. Also, both fiscal and monetary policy are limited by concerns about the political business cycle: that they will be used to satisfy political ends and will end up destabilizing the economy.