18.4 Rational Expectations, Real Business Cycles, and New Classical Macroeconomics

As we have seen, one key difference between classical economics and Keynesian economics is that classical economists believed that the short-

The challenges to Keynesian economics that arose in the 1950s and 1960s from monetarists and from natural rate theorists didn’t rely on classical economics ideas. In other words, the challengers still accepted that an increase in aggregate demand leads to a rise in aggregate output in the short run and that a decrease in aggregate demand leads to a fall in aggregate output in the short run. Instead, they argued that the policy medicine—

New classical macroeconomics is an approach to the business cycle that returns to the classical view that shifts in the aggregate demand curve affect only the aggregate price level, not aggregate output.

In the 1970s and 1980s, however, some economists developed an approach to the business cycle known as new classical macroeconomics, which revived the classical view that shifts in the aggregate demand curve affect only the aggregate price level, not aggregate output. The new approach evolved in two steps. First, some economists challenged traditional arguments about the slope of the short-

Rational Expectations

Rational expectations is the view that individuals and firms make decisions optimally, using all available information.

In the 1970s a concept known as rational expectations had a powerful impact on macroeconomics. Rational expectations, originally introduced by John Muth in 1961, is the view that individuals and firms make decisions optimally, using all available information. Since these expectations are optimal, agents learn from past errors and thus do not systematically repeat past mistakes.

For example, workers and employers bargaining over long-

Adopting rational expectations can significantly alter policy-

According to the rational expectations model of the economy, expected changes in monetary policy have no effect on unemployment and output and only affect the price level.

In the 1970s Robert Lucas of the University of Chicago, in a series of highly influential papers, used the logic of rational expectations to argue that monetary policy can change the level of output and unemployment only if it comes as a surprise to the public. Otherwise, attempts to lower unemployment will simply result in higher prices. According to Lucas’s rational expectations model of the economy, monetary policy isn’t useful in stabilizing the economy after all. In 1995 Lucas won the Nobel Prize in economics for this work, which remains widely admired. However, many—

Why, in the view of many macroeconomists, doesn’t Lucas’s rational expectations model of macroeconomics accurately describe how the economy actually behaves? New Keynesian economics, a set of ideas that became influential in the 1990s, provides an explanation. It argues that market imperfections interact to make many prices in the economy temporarily sticky. For example, one new Keynesian argument points out that monopolists don’t have to be too careful about setting prices exactly “right”: if they set a price a bit too high, they’ll lose some sales but make more profit on each sale; if they set the price too low, they’ll reduce the profit per sale but sell more. As a result, even small costs to changing prices, so-

Over time, new Keynesian ideas combined with actual experience have reduced the practical influence of the rational expectations concept. Nonetheless, the idea of rational expectations served as a useful caution for macroeconomists who had become excessively optimistic about their ability to manage the economy.

Real Business Cycles

In Chapter 9 we introduced the concept of total factor productivity, the amount of output that can be generated with a given level of factor inputs. Total factor productivity grows over time, but that growth isn’t smooth. In the 1980s a number of economists argued that slowdowns in productivity growth, which they attributed to pauses in technological progress, are the main cause of recessions. Real business cycle theory claims that fluctuations in the rate of growth of total factor productivity cause the business cycle.

Real business cycle theory claims that fluctuations in the rate of growth of total factor productivity cause the business cycle.

Believing that the aggregate supply curve is vertical, real business cycle theorists attribute the source of business cycles to shifts of the aggregate supply curve: a recession occurs when a slowdown in total factor productivity growth shifts the aggregate supply curve leftward, and a recovery occurs when a pickup in total factor productivity growth shifts the aggregate supply curve rightward. In the early days of real business cycle theory, the theory’s proponents denied that changes in aggregate demand—and, likewise, macroeconomic policy activism—have any effect on aggregate output.

SUPPLY-SIDE ECONOMICS

During the 1970s a group of economic writers began propounding a view of economic policy that came to be known as “supply-side economics.” The core of this view was the belief that reducing tax rates, and so increasing the incentives to work and invest, would have a powerful positive effect on the growth rate of potential output. The supply-siders urged the government to cut taxes without worrying about matching spending cuts: economic growth, they argued, would offset any negative effects from budget deficits. Some supply-siders even argued that a cut in tax rates would have such a miraculous effect on economic growth that tax revenues—the total amount taxpayers pay to the government—would actually rise. That is, some supply-siders argued that the United States was on the wrong side of the Laffer curve, a hypothetical relationship between tax rates and total tax revenue that slopes upward at low tax rates but turns downward when tax rates are very high.

In the 1970s supply-side economics was enthusiastically supported by the editors of the Wall Street Journal and other figures in the media, and it became popular with politicians. In 1980 Ronald Reagan made supply-side economics the basis of his U.S. presidential campaign.

Because supply-side economics emphasizes supply rather than demand, and because the supply-siders themselves are harshly critical of Keynesian economics, it might seem as if supply-side theory belongs in our discussion of new classical macroeconomics. But unlike rational expectations and real business cycle theory, supply-side economics is generally dismissed by economic researchers.

The main reason for this dismissal is lack of supporting evidence. Almost all economists agree that tax cuts increase incentives to work and invest. But attempts to estimate these incentive effects indicate that at current Canadian and U.S. tax levels, the positive incentive effects aren’t nearly strong enough to support the strong claims made by supply-siders. In particular, the supply-side doctrine implies that large tax cuts, such as those implemented by Ronald Reagan in the early 1980s, should sharply raise potential output. Yet estimates of potential output by the U.S. Congressional Budget Office and others show no sign of an acceleration in growth after the Reagan tax cuts.

This theory was strongly influential, as shown by the fact that two of the founders of real business cycle theory, Finn Kydland of Carnegie Mellon University and Edward Prescott of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, won the 2004 Nobel Prize in economics. The current status of real business cycle theory, however, is somewhat similar to that of rational expectations. The theory is widely recognized as having made valuable contributions to our understanding of the economy, and it serves as a useful caution against too much emphasis on aggregate demand. But many of the real business cycle theorists themselves now acknowledge that their models need an upward-sloping aggregate supply curve to fit the economic data—and that this gives aggregate demand a potential role in determining aggregate output. And as we have seen, policy-makers strongly believe that aggregate demand policy has an important role to play in fighting recessions.

TOTAL FACTOR PRODUCTIVITY AND THE BUSINESS CYCLE

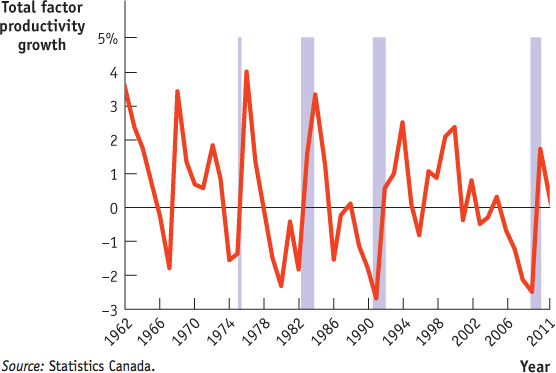

Real business cycle theory argues that fluctuations in the rate of growth of total factor productivity are the principal cause of business cycles. Although many macroeconomists dispute that claim, the theory did draw attention to the fact that there is a strong correlation between the rate of total factor productivity growth and the business cycle. Figure 18-6 shows the annual rate of total factor productivity growth estimated by Statistics Canada. The shaded areas represent recessions. Clearly, recessions tend also to be periods in which the growth of total factor productivity slows sharply or even turns negative. And real business cycle theorists deserve a lot of credit for drawing economists’ attention to this fact.

There are, however, disputes about how to interpret this correlation. In the early days of real business cycle theory, proponents argued that productivity fluctuations are entirely the result of uneven technological progress. Critics pointed out, however, that in really severe recessions, like those of the early 1980s, 1990–1991, or 2008–2009, total factor productivity actually declines.3 If real business cycle theorists were correct, then the level of technology actually regressed during those periods—something that is hard to believe.

So what accounts for declining total factor productivity during recessions? Some economists argue that it is a result, not a cause, of economic downturns. An example may be helpful. Suppose we measure productivity at the local post office by the number of pieces of mail handled, divided by the number of postal workers. Since the post office doesn’t lay off workers whenever there’s a slow mail day, days in which there is a fall in the amount of mail to process will seem to be days in which workers are especially unproductive. In other words, the slump in business is causing the apparent decline in productivity, not the other way around.

It’s now widely accepted that some of the correlation between total factor productivity and the business cycle is the result of the effect of the business cycle on productivity, rather than the reverse. But the main direction of causation is a subject of continuing research.

Quick Review

According to new classical macroeconomics, the short-run aggregate supply curve is vertical after all. It contains two branches: the rational expectations model and real business cycle theory.

Rational expectations claims that people take all information into account and formulate optimal forecasts. The rational expectations model of the economy claims that only unexpected changes in monetary policy affect aggregate output and employment; expected changes only alter the price level.

New Keynesian economics argues that due to market imperfections that create price stickiness, the aggregate supply curve is upward-sloping; therefore changes in aggregate demand affect aggregate output and employment.

Real business cycle theory argues that fluctuations in the rate of total factor productivity growth cause the business cycle.

New Keynesian ideas and events have diminished the acceptance of the rational expectations model, while real business cycle theory has been undermined by its implication that technology regresses during deep recessions. It is now generally believed that the aggregate supply curve is upward-sloping.

Check Your Understanding 18-4

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 18-4

In late 2008, as it became clear that Canada, like the United States, was experiencing a recession, the Bank of Canada reduced its target for the overnight interest rate to near zero, as part of a larger aggressively expansionary monetary policy stance. (In the United States the Fed made similar moves, including what they called “quantitative easing.”) Most observers agreed that the BOC’s aggressive monetary expansion helped reduce the length and severity of the 2008–2009 recession.

What would rational expectations theorists say about this conclusion?

What would real business cycle theorists say?

Rational expectations theorists would argue that only unexpected changes in the money supply would have any short-run effect on economic activity. They would also argue that expected changes in the money supply would affect only the aggregate price level, with no short-run effect on aggregate output. So such theorists would give credit to the BOC for limiting the severity of the 2008–2009 recession only if the BOC’s monetary policy had been more aggressive than individuals expected during this period.

Real business cycle theorists would argue that the BOC’s policy had no effect on ending the 2008–2009 recession because they believe that fluctuations in aggregate output are caused largely by changes in total factor productivity.