19.4 Exchange Rates and Macroeconomic Policy

When the euro was created in 1999, there were celebrations across the nations of Europe—

Why did Britain say no? Part of the answer was national pride: if Britain gave up the pound, it would also have to give up currency that bears the portrait of the queen. But there were also serious economic concerns about giving up the pound in favour of the euro. British economists who favoured adoption of the euro argued that if Britain used the same currency as its neighbours, the country’s international trade would expand and its economy would become more productive. But other economists pointed out that adopting the euro would take away Britain’s ability to have an independent monetary policy and might lead to macroeconomic problems.

As this discussion suggests, the fact that modern economies are open to international trade and capital flows adds a new level of complication to our analysis of macroeconomic policy. Let’s look at three policy issues raised by open-

1. Devaluation and Revaluation of Fixed Exchange Rates

Historically, fixed exchange rates haven’t been permanent commitments. Sometimes countries with a fixed exchange rate switch to a floating rate, as Argentina did in 2001. In other cases, they retain a fixed rate but change the target exchange rate. Such adjustments in the target were common during the Bretton Woods era described in the preceding For Inquiring Minds. For example, in 1967 Britain changed the exchange rate of the pound against the U.S. dollar from US$2.80 per £1 to US$2.40 per £1. A modern example is Argentina, which maintained a fixed exchange rate against the dollar from 1991 to 2001 but switched to a floating exchange rate at the end of 2001.

A devaluation is a reduction in the value of a currency that is set under a fixed exchange rate regime.

A reduction in the value of a currency that is set under a fixed exchange rate regime is called a devaluation. As we’ve already learned, a depreciation is a downward move in a currency. A devaluation is a depreciation that is due to a revision in a fixed exchange rate target. An increase in the value of a currency that is set under a fixed exchange rate regime is called a revaluation.

A revaluation is an increase in the value of a currency that is set under a fixed exchange rate regime.

A devaluation, like any depreciation, makes domestic goods cheaper in terms of foreign currency, which leads to higher exports. At the same time, it makes foreign goods more expensive in terms of domestic currency, which reduces imports. The effect is to increase the balance of payments on current account. Similarly, a revaluation makes domestic goods more expensive in terms of foreign currency, which reduces exports, and makes foreign goods cheaper in domestic currency, which increases imports. So a revaluation reduces the balance of payments on current account.

Devaluations and revaluations serve two purposes under fixed exchange rates. First, they can be used to eliminate shortages or surpluses in the foreign exchange market. For example, in 2010 some economists and politicians were urging China to revalue the yuan because they believed that China’s exchange rate policy unfairly aided Chinese exports.

Second, devaluation and revaluation can be used as tools of macroeconomic policy. A devaluation, by increasing exports and reducing imports, increases aggregate demand. So a devaluation can be used to reduce or eliminate a recessionary gap. A revaluation has the opposite effect, reducing aggregate demand. So a revaluation can be used to reduce or eliminate an inflationary gap.

2. Monetary Policy Under Floating Exchange Rates

Under a floating exchange rate regime, a country’s central bank retains its ability to pursue monetary policy that is independent of other countries: it can increase aggregate demand by cutting the interest rate or decrease aggregate demand by raising the interest rate.4 A floating exchange rate regime permits a country to conduct monetary policy that is independent of other countries.

But the exchange rate adds another dimension to the effects of monetary policy. To see why, let’s return to the hypothetical country of Genovia and ask what happens if the central bank cuts the interest rate.

Just as in a closed economy, a lower interest rate leads to higher investment spending and higher consumer spending. But the decline in the interest rate also affects the foreign exchange market. Foreigners have less incentive to move funds into Genovia because they will receive a lower interest rate on their loans. As a result, they have less need to exchange Canadian dollars for genovs, so the demand for genovs falls. At the same time, Genovians have more incentive to move funds abroad because the interest rate on loans at home has fallen, making investments outside the country more attractive. As a result, they need to exchange more genovs for Canadian dollars, so the supply of genovs rises.

Figure 19-13 shows the effect of an interest rate reduction on the foreign exchange market. The demand curve for genovs shifts leftward, from D1 to D2, and the supply curve shifts rightward, from S1 to S2. The equilibrium exchange rate, as measured in Canadian dollars per genov, falls from XR1 to XR2. That is, a reduction in the Genovian interest rate causes the genov to depreciate.

The depreciation of the genov, in turn, affects aggregate demand. We’ve already seen that a devaluation—

In other words, monetary policy under floating rates has effects beyond those we’ve described in looking at closed economies. In a closed economy, a reduction in the interest rate leads to a rise in aggregate demand because it leads to more investment spending and consumer spending. In an open economy with a floating exchange rate, the interest rate reduction leads to increased investment spending and consumer spending, but it also increases aggregate demand in another way: it leads to a currency depreciation, which increases exports and reduces imports, and further increases aggregate demand.

3. International Business Cycles

Up to this point, we have discussed macroeconomics, even in an open economy, as if all demand shocks originate from the domestic economy. In reality, however, economies sometimes face shocks coming from abroad. For example, recessions in the United States have historically led to economic slowdowns in Canada.

The key point is that changes in aggregate demand affect the demand for goods and services produced abroad as well as at home: other things equal, a recession leads to a fall in imports and an expansion leads to a rise in imports. And one country’s imports are another country’s exports. This link between aggregate demand in different national economies is one reason business cycles in different countries sometimes—but not always—seem to be synchronized. The prime example is the Great Depression, which affected countries around the world.

The extent of this link depends, however, on the exchange rate regime. To see why, think about what happens if a recession abroad reduces the demand for Genovia’s exports. A reduction in foreign demand for Genovian goods and services is also a reduction in demand for genovs in the foreign exchange market. If Genovia has a fixed exchange rate, it responds to this decline with exchange market intervention. But if Genovia has a floating exchange rate, the genov depreciates. Because Genovian goods and services become cheaper to foreigners when the demand for exports falls, the quantity of goods and services exported doesn’t fall by as much as it would under a fixed rate. At the same time, the fall in the genov makes imports more expensive to Genovians, leading to a fall in imports. Both effects limit the decline in Genovia’s aggregate demand compared to what it would have been under a fixed exchange rate.

One of the virtues of a floating exchange rate, according to advocates of such exchange rates, is that they help insulate countries from recessions originating abroad. This theory looked pretty good in the early 2000s: Britain, with a floating exchange rate, managed to stay out of a recession that affected the rest of Europe, and Canada, which also has a floating rate, suffered a less severe recession than the United States.

In 2008, however, the financial crisis that began in the United States led to a recession in virtually every country. In this case, it appears that the international linkages among financial markets were much stronger than any insulation from overseas disturbances provided by floating exchange rates.

THE JOY OF A DEVALUED POUND

Earlier in the chapter, we mentioned the Exchange Rate Mechanism, the system of European fixed exchange rates that paved the way for the creation of the euro in 1999. Britain joined that system in 1990 but dropped out in 1992. The story of Britain’s exit from the Exchange Rate Mechanism is a classic example of open-economy macroeconomic policy.

Britain originally fixed its exchange rate for both the reasons we described earlier in the chapter: British leaders believed that a fixed exchange rate would help promote international trade, and they also hoped that it would help fight inflation. But by 1992 Britain was suffering from high unemployment: the unemployment rate in September 1992 was over 10%. And as long as the country had a fixed exchange rate, there wasn’t much the government could do. In particular, the government wasn’t able to cut interest rates because it was using high interest rates to help support the value of the pound.

In the summer of 1992, investors began speculating against the pound—selling pounds in the expectation that the currency would drop in value. As its foreign reserves dwindled, this speculation forced the British government’s hand. On September 16, 1992, Britain abandoned its fixed exchange rate. The pound promptly dropped 20% against the German mark, the most important European currency at the time.

At first, the devaluation of the pound greatly damaged the prestige of the British government. But the Chancellor of the Exchequer—the counterpart of Canada’s federal minister of finance—claimed to be happy about it. “My wife has never before heard me singing in the bath,” he told reporters. There were several reasons for his joy. One was that the British government would no longer have to engage in large-scale exchange market intervention to support the pound’s value. Another was that devaluation increases aggregate demand, so the pound’s fall would help reduce British unemployment. Finally, because Britain no longer had a fixed exchange rate, it was free to pursue an expansionary monetary policy to fight its slump.

Indeed, events made it clear that the chancellor’s joy was well founded. British unemployment fell over the next two years, even as the unemployment rate rose in France and Germany. One person who did not share in the improving employment picture, however, was the chancellor himself. Soon after his remark about singing in the bath, he was fired.

Quick Review

Countries can change fixed exchange rates. Devaluation or revaluation can help reduce surpluses or shortages in the foreign exchange market and can increase or reduce aggregate demand.

In an open economy with a floating exchange rate, interest rates also affect the exchange rate, and so monetary policy affects aggregate demand through the effects of the exchange rate on imports and exports.

Because one country’s imports are another country’s exports, business cycles are sometimes synchronized across countries. However, floating exchange rates may reduce this link.

Check Your Understanding 19-4

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 19-4

Look at the data in Figure 19-12. Where do you see devaluations and revaluations of the franc against the mark?

The devaluations and revaluations most likely occurred in those periods when there was a sudden change in the franc–mark exchange rate: 1974, 1976, the early 1980s, 1986, and 1993–1994.

In the late 1980s Canadian economists argued that the high interest rate policies of the Bank of Canada weren’t just causing high unemployment—they were also making it hard for Canadian manufacturers to compete with the United States. Explain this complaint, using our analysis of how monetary policy works under floating exchange rates.

The high Canadian interest rates would likely have caused an increase in capital inflows to Canada. To obtain these assets (which yielded a relatively higher interest rate) in Canada, investors would first have had to obtain Canadian dollars. The increase in the demand for the Canadian dollar would have caused the Canadian dollar to appreciate. This appreciation of the Canadian currency would have raised the price of Canadian goods to foreigners (measured in terms of the foreign currency). This would have made it more difficult for Canadian firms to compete in other markets.

War of the Earthmovers

Visit a construction site almost anywhere in the world, and odds are that the earthmoving equipment you see—the tractors, dump trucks, excavators, graders, scrapers, and so on—is made by one of two companies, America’s Caterpillar or Japan’s Komatsu. Caterpillar and Komatsu both rely heavily on exports, rather than selling only to their domestic markets, and have been fierce competitors for three decades, with first one company, then the other, seemingly on the ropes.

Ask the companies’ leaders to explain the course of this seesawing competitive struggle, and they will tell a tale of corporate cultures and management decisions. Caterpillar, the story goes, entered the 1980s filled with complacency thanks to its longtime dominance of the earthmoving industry, only to face a shock from Komatsu that almost drove it to the brink. Then Caterpillar reformed its management practices, regaining the upper hand in the 1990s, and Komatsu found itself in danger of failing, until reinvigorated management stabilized the company again.

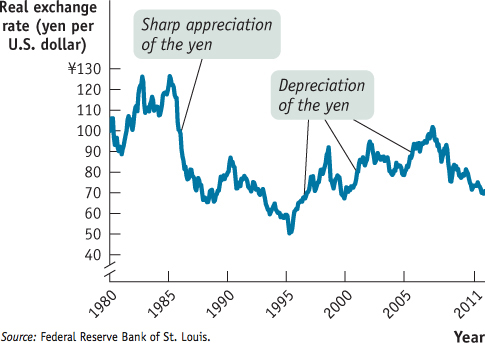

But is this the whole story? Not exactly. Management decisions were no doubt crucial to both firms, but so were movements in the exchange rate. Figure 19-14 shows the real exchange rate between the United States and Japan, using consumer prices, from 1980 to 2011. The figure immediately suggests one reason Caterpillar was able to recover from the shock of competition in the 1980s: a sharp appreciation of the Japanese yen beginning in 1985. And Komatsu’s ability to survive Caterpillar’s resurgence was surely helped by the slide in the yen after 1995, and especially after 2000.

The two companies seemed to have settled into relatively stable positions, with Caterpillar the bigger firm but Komatsu is also doing well thanks in part to rapid growth in demand from China. At the time of writing, many argue that the United States and Japan are themselves engaged in a currency war—with each nation racing to lower the value of (devalue) their currencies in an attempt to boost their trade balance and stimulate aggregate demand. This kind of currency war will definitely have an impact on the Caterpillar/Komatsu rivalry.

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

Why does the yen–dollar exchange rate matter so much for the fortunes of Caterpillar and Komatsu?

Why does the yen–dollar exchange rate matter so much for the fortunes of Caterpillar and Komatsu?

Why does the figure present the real rather than the nominal exchange rate? Do you think this makes an important difference to the story?

Why does the figure present the real rather than the nominal exchange rate? Do you think this makes an important difference to the story?

In 2011, Japanese policy-makers were discussing possible sales of yen on the foreign exchange market. How would this affect the Caterpillar/Komatsu rivalry?

In 2011, Japanese policy-makers were discussing possible sales of yen on the foreign exchange market. How would this affect the Caterpillar/Komatsu rivalry?

The so-called currency war between the United States and Japan will not only have effects on their own trade balances; it will also indirectly affect other countries’ trade balance. How will this currency war affect Canada’s trade balance?

The so-called currency war between the United States and Japan will not only have effects on their own trade balances; it will also indirectly affect other countries’ trade balance. How will this currency war affect Canada’s trade balance?