1.2 Interaction: How Economies Work

Interaction of choices—

As we learned in the Introduction, an economy is a system for coordinating the productive activities of many people. In a market economy like we live in, coordination takes place without any coordinator: each individual makes his or her own choices. Yet those choices are by no means independent of one another: each individual’s opportunities, and hence choices, depend to a large extent on the choices made by other people. So to understand how a market economy behaves, we have to examine this interaction in which my choices affect your choices, and vice versa.

When studying economic interaction, we quickly learn that the end result of individual choices may be quite different from what any one individual intends. For example, over the past century North American farmers have eagerly adopted new farming techniques and crop strains that have reduced their costs and increased their yields. Clearly, it’s in the interest of each farmer to keep up with the latest farming techniques.

But the end result of each farmer trying to increase his or her own income has actually been to drive many farmers out of business. Because Canadian farmers have been so successful at producing larger yields, agricultural prices have steadily fallen. These falling prices have reduced the incomes of many farmers, and as a result fewer and fewer people find farming worth doing. That is, an individual farmer who plants a better variety of corn is better off; but when many farmers plant a better variety of corn, the result may be to make farmers as a group worse off.

A farmer who plants a new, more productive corn variety doesn’t just grow more corn. Such a farmer also affects the market for corn through the increased yields attained, with consequences that will be felt by other farmers, consumers, and beyond.

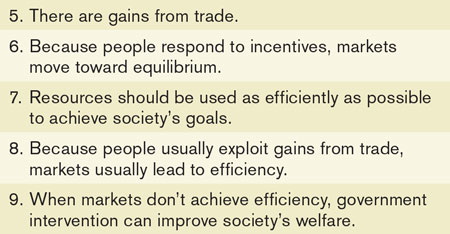

Just as there are four economic principles that underlie individual choice, there are five principles that underlie the economics of interaction. These five principles are summarized in Table 1-2. We will now examine each of these principles more closely.

Principle #5: There Are Gains from Trade

In a market economy, individuals engage in trade: they provide goods and services to others and receive goods and services in return.

Why do the choices I make interact with the choices you make? A family could try to take care of all its own needs—

The reason we have an economy, not many self-

There are gains from trade: people can get more of what they want through trade than they could if they tried to be self-

There are gains from trade.

Gains from trade arise from this division of tasks, which economists call specialization—a situation in which different people each engage in a different task, specializing in those tasks that they are good at performing. The advantages of specialization, and the resulting gains from trade, were the starting point for Adam Smith’s 1776 book The Wealth of Nations, which many regard as the beginning of economics as a discipline. Smith’s book begins with a description of an eighteenth-

This increase in output is due to specialization: each person specializes in the task that he or she is good at performing.

One man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts it, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving the head; to make the head requires two or three distinct operations; to put it on, is a particular business, to whiten the pins is another; it is even a trade by itself to put them into the paper; and the important business of making a pin is, in this manner, divided into about eighteen distinct operations …. Those ten persons, therefore, could make among them upwards of forty-

The same principle applies when we look at how people divide tasks among themselves and trade in an economy. The economy, as a whole, can produce more when each person specializes in a task and trades with others.

The benefits of specialization are the reason a person typically chooses only one career. It takes many years of study and experience to become a doctor; it also takes many years of study and experience to become a commercial airline pilot. Many doctors might well have had the potential to become excellent pilots, and vice versa; but it is very unlikely that anyone who decided to pursue both careers would be as good a pilot or as good a doctor as someone who decided at the beginning to specialize in that field. So it is to everyone’s advantage that individuals specialize in their career choices.

Markets are what allow a doctor and a pilot to specialize in their own fields. Because markets for commercial flights and for doctors’ services exist, a doctor is assured that she can find a flight and a pilot is assured that he can find a doctor. As long as individuals know that they can find the goods and services they want in the market, they are willing to forgo self-

Principle #6: Markets Move Toward Equilibrium

It’s a busy afternoon at the supermarket; there are long lines at the checkout counters. Then one of the previously closed cash registers opens. What happens? The first thing, of course, is a rush to that register. After a couple of minutes, however, things will have settled down; shoppers will have rearranged themselves so that the line at the newly opened register is about the same length as the lines at all the other registers.

How do we know that? We know from our fourth principle that people will exploit opportunities to make themselves better off. This means that people will rush to the newly opened register in order to save time standing in line. And things will settle down when shoppers can no longer improve their position by switching lines—

An economic situation is in equilibrium when no individual would be better off doing something different.

A story about supermarket checkout lines may seem to have little to do with how individual choices interact, but in fact it illustrates an important principle. A situation in which individuals cannot make themselves better off by doing something different—

Recall the story about the mythical Jiffy Lube, where it was supposedly cheaper to leave your car for an oil change than to pay for parking. If the opportunity had really existed and people were still paying $30 to park in garages, the situation would not have been an equilibrium. And that should have been a giveaway that the story couldn’t be true. In reality, people would have seized an opportunity to park cheaply, just as they seize opportunities to save time at the checkout line. And in so doing they would have eliminated the opportunity! Either it would have become very hard to get an appointment for an oil change or the price of a lube job would have increased to the point that it was no longer an attractive option (unless you really needed a lube job). This brings us to our sixth principle:

CHOOSING SIDES

Why do people in North America drive on the right side of the road? Of course, it’s the law. But long before it was the law, it was an equilibrium.

Before there were formal traffic laws, there were informal “rules of the road,” practices that everyone expected everyone else to follow. These rules included an understanding that people would normally keep to one side of the road. In some places, such as England, the rule was to keep to the left; in others, such as France, it was to keep to the right.

Why would some places choose the right and others, the left? That’s not completely clear, although it may have depended on the dominant form of traffic. Men riding horses and carrying swords on their left hip preferred to ride on the left (think about getting on or off the horse, and you’ll see why). On the other hand, right-

In any case, once a rule of the road was established, there were strong incentives for each individual to stay on the “usual” side of the road: those who didn’t would keep colliding with oncoming traffic. So once established, the rule of the road would be self-

But what about pedestrians? There are no laws—

Because people respond to incentives, markets move toward equilibrium.

As we will see, markets usually reach equilibrium via changes in prices, which rise or fall until no opportunities for individuals to make themselves better off remain.

The concept of equilibrium is extremely helpful in understanding economic interactions because it provides a way of cutting through the sometimes complex details of those interactions. To understand what happens when a new line is opened at a supermarket, you don’t need to worry about exactly how shoppers rearrange themselves, who moves ahead of whom, which register just opened, and so on. What you need to know is that any time there is a change, the situation will move to an equilibrium.

The fact that markets move toward equilibrium is why we can depend on them to work in a predictable way. In fact, we can trust markets to supply us with the essentials of life. For example, people who live in big cities can be sure that the supermarket shelves will always be fully stocked. Why? Because if some merchants who distribute food didn’t make deliveries, a big profit opportunity would be created for any merchant who did—

A market economy, as we have seen, allows people to achieve gains from trade. But how do we know how well such an economy is doing? The next principle gives us a standard to use in evaluating an economy’s performance.

Principle #7: Resources Should Be Used Efficiently to Achieve Society’s Goals

An economy is efficient if it takes all opportunities to make some people better off without making other people worse off.

Suppose you are taking a course in which the classroom is too small for the number of students—

In our classroom example, there clearly was a way to make everyone better off—

When an economy is efficient, it is producing the maximum gains from trade possible given the resources available. Why? Because there is no way to re-

We can now state our seventh principle:

Resources should be used as efficiently as possible to achieve society’s goals.

Equity means that everyone gets his or her fair share. Since people can disagree about what’s “fair,” equity isn’t as well defined a concept as efficiency.

Should economic policy-

To see this, consider the case of disabled-

Exactly how far policy-

Principle #8: Markets Usually Lead to Efficiency

No branch of the Canadian government is entrusted with ensuring the general economic efficiency of our market economy—

The incentives built into a market economy ensure that resources are usually put to good use and that opportunities to make people better off are not wasted. If a university or college were known for its habit of crowding students into small classrooms while large classrooms went unused, it would soon find its enrollment dropping, putting the jobs of its administrators at risk. The “market” for post-

A detailed explanation of why markets are usually very good at making sure that resources are used well will have to wait until we have studied how markets actually work. But the most basic reason is that in a market economy, in which individuals are free to choose what to consume and what to produce, people normally exploit opportunities for mutual gain—

Because people usually exploit gains from trade, markets usually lead to efficiency.

As we learned in the Introduction, however, there are exceptions to this principle that markets are generally efficient. In cases of market failure, the individual pursuit of self-

Principle #9: When Markets Don’t Achieve Efficiency, Government Intervention Can Improve Society’s Welfare

Let’s recall from the Introduction the nature of the market failure caused by traffic congestion—a commuter driving to work has no incentive to take into account the cost that his or her action inflicts on other drivers in the form of increased traffic congestion. There are several possible remedies to this situation; examples include charging road tolls, subsidizing the cost of public transportation, and taxing sales of gasoline to individual drivers. All these remedies work by changing the incentives of would-be drivers, motivating them to drive less and use alternative transportation. But they also share another feature: each relies on government intervention in the market. This brings us to our ninth principle:

When markets don’t achieve efficiency, government intervention can improve society’s welfare.

That is, when markets go wrong, an appropriately designed government policy can sometimes move society closer to an efficient outcome by changing how society’s resources are used.

A very important branch of economics is devoted to studying why markets fail and what policies should be adopted to improve social welfare. These problems and their remedies are commonly studied in texts on microeconomics; but, briefly, there are three principal ways in which they fail:

Individual actions have side effects that are not properly taken into account by the market. An example is an action that causes pollution.

One party prevents mutually beneficial trades from occurring in an attempt to capture a greater share of resources for itself. An example is a drug company that prices a drug higher than the cost of producing it, making it unaffordable for some people who would benefit from it.

Some goods, by their very nature, are unsuited for efficient management by markets. An example of such a good is air traffic control.

An important part of your education in economics is learning to identify not just when markets work but also when they don’t work, and to judge what government policies are appropriate in each situation.

RESTORING EQUILIBRIUM ON THE FREEWAYS

Back in 1994 a powerful earthquake struck the Los Angeles area, causing several freeway bridges to collapse and thereby disrupting the normal commuting routes of hundreds of thousands of drivers. The events that followed offer a particularly clear example of interdependent decision-making—in this case, the decisions of commuters about how to get to work.

In the immediate aftermath of the earthquake, there was great concern about the impact on traffic, since motorists would now have to crowd onto alternative routes or detour around the blockages by using city streets. Public officials and news programs warned commuters to expect massive delays and urged them to avoid unnecessary travel, reschedule their work to commute before or after the rush, or use mass transit. These warnings were unexpectedly effective. In fact, so many people heeded them that in the first few days following the quake, those who maintained their regular commuting routine actually found the drive to and from work faster than before.

Of course, this situation could not last. As word spread that traffic was relatively light, people abandoned their less convenient new commuting methods and reverted to their cars—and traffic got steadily worse. Within a few weeks after the quake, serious traffic jams had appeared. After a few more weeks, however, the situation stabilized: the reality of worse-than-usual congestion discouraged enough drivers to prevent the nightmare of citywide gridlock from materializing. Los Angeles traffic, in short, had settled into a new equilibrium, in which each commuter was making the best choice he or she could, given what everyone else was doing.

This was not, by the way, the end of the story: fears that the city would strangle on traffic led local authorities to repair the roads with record speed. A mere 18 months after the quake, all the freeways were back to normal.

Quick Review

Most economic situations involve the interaction of choices, sometimes with unintended results. In a market economy, interaction occurs via trade between individuals.

Individuals trade because there are gains from trade, which arise from specialization. Markets usually move toward equilibrium because people exploit gains from trade.

To achieve society’s goals, the use of resources should be efficient. But equity, as well as efficiency, may be desirable in an economy. There is often a trade-off between equity and efficiency.

Except for certain well-defined exceptions, markets are normally efficient. When markets fail to achieve efficiency, government intervention can improve society’s welfare.

Check Your Understanding 1-2

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 1-2

Explain how each of the following situations illustrates one of the five principles of interaction.

Using a university website, any student who wants to sell a used textbook for at least $30 is able to sell it to someone who is willing to pay $30.

At a college tutoring co-op, students can arrange to provide tutoring in subjects they are good in (like economics) in return for receiving tutoring in subjects they are poor in (like philosophy).

The local municipality imposes a law that requires bars and nightclubs near residential areas to keep their noise levels below a certain threshold.

To provide better care for low-income patients, the province has decided to close some underutilized neighbourhood clinics and shift funds to nearby hospitals.

On a university website, books of a given title with approximately the same level of wear and tear sell for about the same price.

This illustrates the concept that markets usually lead to efficiency. Any seller who wants to sell a book for at least $30 does indeed sell to someone who is willing to buy a book for $30. As a result, there is no way to change how used textbooks are distributed among buyers and sellers in a way that would make one person better off without making someone else worse off.

This illustrates the concept that there are gains from trade. Students trade tutoring services based on their different abilities in academic subjects.

This illustrates the concept that when markets don’t achieve efficiency, government intervention can improve society’s welfare. In this case the market, left alone, will permit bars and nightclubs to impose costs on their neighbours in the form of loud music, costs that the bars and nightclubs have no incentive to take into account. This is an inefficient outcome because society as a whole can be made better off if bars and nightclubs are induced to reduce their noise.

This illustrates the concept that resources should be used as efficiently as possible to achieve society’s goals. By closing neighbourhood clinics and shifting funds to the main hospital, better health care can be provided at a lower cost.

This illustrates the concept that markets move toward equilibrium. Here, because books with the same amount of wear and tear sell for about the same price, no buyer or seller can be made better off by engaging in a different trade than he or she undertook. This means that the market for used textbooks has moved to an equilibrium.

Which of the following describes an equilibrium situation? Which does not? Explain your answer.

The restaurants across the street from the university dining hall serve better-tasting and cheaper meals than those served at the university dining hall. The vast majority of students continue to eat at the dining hall.

You currently take the bus to work. Although riding your bicycle is cheaper, the ride takes longer. So you are willing to pay the higher transit fare in order to save time.

This does not describe an equilibrium situation. Many students should want to change their behaviour and switch to eating at the restaurants. Therefore, the situation described is not an equilibrium. An equilibrium will be established when students are equally as well off eating at the restaurants as eating at the dining hall—which would happen if, say, prices at the restaurants were higher than at the dining hall.

This does describe an equilibrium situation. By changing your behaviour and riding a bicycle, you would not be made better off. Therefore, you have no incentive to change your behaviour.