4.4 Controlling Quantities

A licence gives its owner the right to supply a good.

In the 1930s, New York City instituted a system of licensing for taxicabs: only taxis with a special licence called a “medallion” were allowed to pick up passengers. Because this system was intended to ensure quality, medallion owners were supposed to maintain certain standards, including safety and cleanliness. A total of 11 787 medallions were issued, with taxi owners paying $10 for each medallion.

In 1995, there were still only 11 787 licensed taxicabs in New York, even though the city had meanwhile become the financial capital of the world, a place where hundreds of thousands of people in a hurry tried to hail a cab every day. (An additional 400 medallions were issued in 1995, and after several rounds of sales of additional medallions, today there are 13 128 medallions.)

The result of this restriction on the number of taxis was that a New York City taxi medallion became very valuable: if you wanted to operate a taxi in New York, you had to lease a medallion from someone else or buy one for a going price of several hundred thousand dollars.

It turns out that this story is not unique; other cities introduced similar medallion systems in the 1930s and, like New York, have issued few new medallions since. In San Francisco and Boston, as in New York, taxi medallions trade for six-

In Toronto, standard taxi licences come in the form of a special numbered plate that, like a New York City taxi medallion, must be affixed to the cab. Fifteen hundred of these standard taxi licences were issued in 1953 and no new plates were issued until 1961. New licensing rules in 1963 allowed these licences to be sold on the open market—

In 1998, Toronto decided to introduce a new class of licence with the sale of 1400 new Ambassador taxi licences, and going forward, no new standard licences would ever be issued. Unlike a standard licence, Ambassador licences can’t be sold, leased, or otherwise transferred—

By 2013, there were about 4850 taxi licences in Toronto of both types. Standard licences sold for about $300 000 and most owners of Ambassador licences wished they too could sell or lease their plates to someone else. Interestingly, a 2013 report to the city licensing commission recommended moving to a single “harmonized” licence that could not be sold or leased for long periods of time. If adopted, this proposal could improve customer service by ensuring that owner-

In Vancouver, the city issues taxi licences to only four companies, charging them $522 for each licence. These companies then sell shares in the licence, dividing them into two shares: one for the day shift and one for the night shift. Each share comes with the right to drive a car, but also pays dividends from real estate the taxi company owns. These shares cost about $300 000 to $400 000, making the cost of acquiring rights to an entire car (two shares) about as costly as obtaining a taxi medallion in New York.

A quantity control, or quota, is an upper limit on the quantity of some good that can be bought or sold. The total amount of the good that can be legally transacted is the quota limit.

A taxi licensing or medallion system is a form of quantity control, or quota, by which the government regulates the quantity of a good that can be bought and sold rather than the price at which it is transacted. The total amount of the good that can be transacted under the quantity control is called the quota limit. Typically, the government limits quantity in a market by issuing licences; only people with a licence can legally supply the good.

There are many other cases of quantity controls, ranging from limits on how much foreign currency (for instance, British pounds or Mexican pesos) people are allowed to buy to the quantity of snow crabs Newfoundland and Labrador fishing boats are allowed to catch. Notice, by the way, that although there are price controls on both sides of the equilibrium price—

Some attempts to control quantities are undertaken for good economic reasons, some for bad ones. In many cases, as we will see, quantity controls introduced to address a temporary problem become politically hard to remove later because the beneficiaries don’t want them abolished, even after the original reason for their existence is long gone. But whatever the reasons for such controls, they have certain predictable—

The Anatomy of Quantity Controls

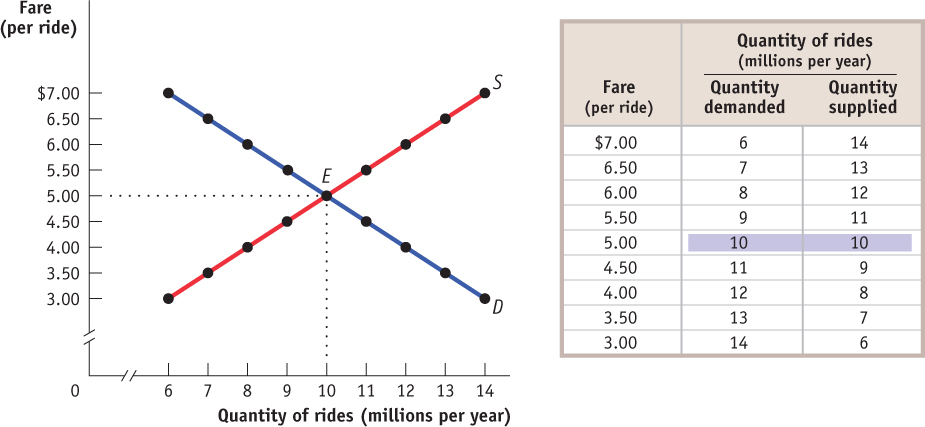

To understand why a New York City taxi medallion is worth so much money, we consider a simplified version of the market for taxi rides, shown in Figure 4-7. Just as we assumed in the analysis of rent control that all apartments are the same, we now suppose that all taxi rides are the same—

The New York medallion system limits the number of taxis, but each taxi driver can offer as many rides as he or she can manage. (Now you know why New York taxi drivers are so aggressive!) To simplify our analysis, however, we will assume that a medallion system limits the number of taxi rides that can legally be given to 8 million per year.

The demand price of a given quantity is the price at which consumers will demand that quantity.

Until now, we have derived the demand curve by answering questions of the form: “What is the maximum number of taxi rides passengers will want to take if the price is $5 per ride?” But it is possible to reverse the question and ask instead: “What is the maximum price per ride consumers will pay to buy 10 million rides per year?” The price at which consumers want to buy a given quantity—

The supply price of a given quantity is the price at which producers will supply that quantity.

Similarly, the supply curve represents the answer to questions of the form: “What is the maximum number of taxi rides drivers are willing to supply at a price of $5 each?” But we can also reverse this question to ask: “What is the minimum price at which suppliers would be willing to supply 10 million rides per year?” The price at which suppliers will supply a given quantity—

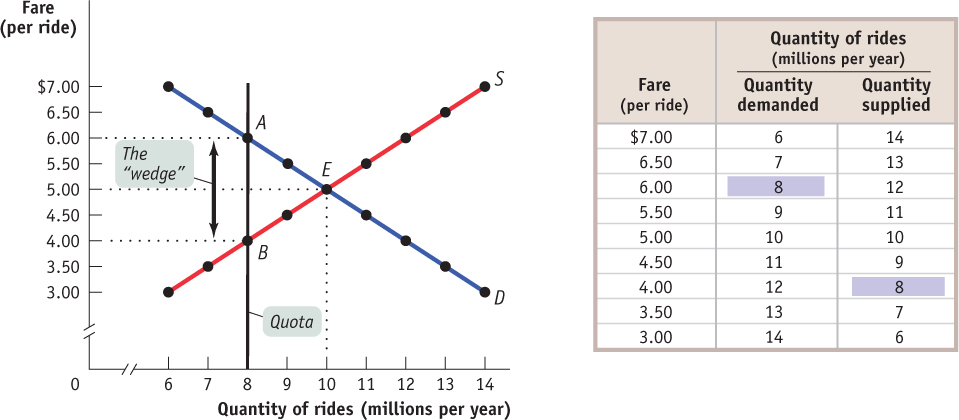

Now we are ready to analyze a quota. We have assumed that the city government limits the quantity of taxi rides to 8 million per year. Medallions, each of which carries the right to provide a certain number of taxi rides per year, are made available to selected people in such a way that a total of 8 million rides will be provided. Medallion-

Figure 4-8 shows the resulting market for taxi rides, with the black vertical line at 8 million rides per year representing the quota limit. Because the quantity of rides is limited to 8 million, consumers must be at point A on the demand curve, corresponding to the shaded entry in the demand schedule: the demand price of 8 million rides is $6 per ride. Meanwhile, taxi drivers must be at point B on the supply curve, corresponding to the shaded entry in the supply schedule: the supply price of 8 million rides is $4 per ride.

But how can the price received by taxi drivers be $4 when the price paid by taxi riders is $6? The answer is that in addition to the market in taxi rides, there is also a market in medallions. Medallion-

To see how this all works, consider two imaginary taxi drivers, Sunil and Harriet. Sunil has a medallion but can’t use it because he’s recovering from a severely sprained wrist. So he’s looking to rent his medallion out to someone else. Harriet doesn’t have a medallion but would like to rent one. Furthermore, at any point in time, there are many other people like Harriet who would like to rent a medallion. Suppose Sunil agrees to rent his medallion to Harriet. To make things simple, assume that any driver can give only one ride per day and that Sunil is renting his medallion to Harriet for one day. What rental price will they agree on?

To answer this question, we need to look at the transactions from the viewpoints of both drivers. Once she has the medallion, Harriet knows she can make $6 per day—

A quantity control, or quota, drives a wedge between the demand price and the supply price of a good; that is, the price paid by buyers ends up being higher than that received by sellers.

It is no coincidence that $2 is exactly the difference between $6, the demand price of 8 million rides, and $4, the supply price of 8 million rides. In every case in which the supply of a good is legally restricted, there is a wedge between the demand price of the quantity transacted and the supply price of the quantity transacted. This wedge, illustrated by the double-

The difference between the demand and supply price at the quota limit is the quota rent, the earnings that accrue to the licence-

So Figure 4-8 also illustrates the quota rent in the market for taxi rides. The quota limits the quantity of rides to 8 million per year, a quantity at which the demand price of $6 exceeds the supply price of $4. The wedge between these two prices, $2, is the quota rent that results from the restrictions placed on the quantity of taxi rides in this market.

But wait a second. What if Sunil doesn’t rent out his medallion? What if he uses it himself? Doesn’t this mean that he gets a price of $6? No, not really. Even if Sunil doesn’t rent out his medallion, he could have rented it out, which means that the medallion has an opportunity cost of $2: if Sunil decides to use his own medallion and drive his own taxi rather than renting his medallion to Harriet, the $2 represents his opportunity cost of not renting out his medallion. That is, the $2 quota rent is now the rental income he forgoes by driving his own taxi.

In effect, Sunil is in two businesses—

Notice, by the way, that quotas—

The Costs of Quantity Controls

Like price controls, quantity controls can have some predictable and undesirable side effects. The first is the by-now-familiar problem of inefficiency due to missed opportunities: quantity controls prevent mutually beneficial transactions from occurring, transactions that would benefit both buyers and sellers. Looking back at Figure 4-8, you can see that starting at the quota limit of 8 million rides, New Yorkers would be willing to pay at least $5.50 per ride for an additional 1 million rides and that taxi drivers would be willing to provide those rides as long as they got at least $4.50 per ride. These are rides that would have taken place if there were no quota limit.

The same is true for the next 1 million rides: New Yorkers would be willing to pay at least $5 per ride when the quantity of rides is increased from 9 to 10 million, and taxi drivers would be willing to provide those rides as long as they got at least $5 per ride. Again, these rides would have occurred without the quota limit.

Only when the market has reached the unregulated market equilibrium quantity of 10 million rides are there no “missed-opportunity rides”—the quota limit of 8 million rides has caused 2 million “missed-opportunity rides.”

Generally, as long as the demand price of a given quantity exceeds the supply price, there is a missed opportunity. A buyer would be willing to buy the good at a price that the seller would be willing to accept, but such a transaction does not occur because it is forbidden by the quota.

And because there are transactions that people would like to make but are not allowed to, quantity controls generate an incentive to evade them or even to break the law. New York’s taxi industry again provides clear examples. Taxi regulation applies only to those drivers who are hailed by passengers on the street. A car service that makes prearranged pickups does not need a medallion. As a result, such hired cars provide much of the service that might otherwise be provided by taxis, as in other cities. In addition, there are substantial numbers of unlicensed cabs that simply defy the law by picking up passengers without a medallion. Because these cabs are illegal, their drivers are completely unregulated, and they generate a disproportionately large share of traffic accidents in New York City.3

In fact, in 2004 the hardships caused by the limited number of New York taxis led city leaders to authorize an increase in the number of licensed taxis. In a series of sales, the city sold 900 new medallions, to bring the total number up to the current 13 128 medallions—a move that certainly cheered New York riders.

But those who already owned medallions were less happy with the increase; they understood that the 900 new taxis would reduce or eliminate the shortage of taxis. As a result, taxi drivers anticipated a decline in their revenues because they would no longer always be assured of finding willing customers. And, in turn, the value of a medallion would fall. So to placate the medallion owners, city officials also raised taxi fares: by 25% in 2004, by 11% in 2006, and again by 17% in 2012. Although taxis are now easier to find, a ride now costs more—and that price increase slightly diminished the newfound cheer of New York taxi riders.

In sum, quantity controls typically create the following undesirable side effects:

Inefficiencies, or missed opportunities, in the form of mutually beneficial transactions that don’t occur

Incentives for illegal activities

THE LOBSTERS OF ATLANTIC CANADA

Forget the various finned species of fish. When it comes to Canada’s fisheries, lobster truly is the “King of Seafood.” This industry employs thousands of people in New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Quebec, and contributed more than $1 billion in export sales in 2012. According to the federal government, lobsters are exported to more than 50 countries worldwide and are one of the exports most closely associated with Canada.

But all is not well in this fishery, which has been hit by several negative shocks in recent years. First, usually about 80% of Canadian lobster exports go to the United States, but demand there has softened since the start of the 2008–2009 recession. This situation is worsened by the appreciation of the Canadian dollar against the U.S. dollar, which put additional downward pressure on the value of Canadian exports. At the same time, landings of lobster in Atlantic Canada and the United States (mostly in the state of Maine) have risen almost 50% in the past 12 years. Catches in 2012 and 2013 have been described as the best seen in years. And while the number of lobster fishing licences is limited and, under current rules, licensed Canadian fishers are restricted in the number of traps they can operate, there is no quota on the number of lobsters they can bring in from those traps.

So demand is down and supply is up, and together these have resulted in prices plummeting from about $9–14/kg in 2005 to about $7.15/kg (or $3.25/lb) in 2013. Nova Scotian fisher Leonard LeBlanc told the CBC that he couldn’t remember prices this low in 30 years. “At $3.25 [per pound], we’re not covering our costs; we’re just trying to mitigate the expenses—at least pay some of them—not all of them and we’re praying we don’t have any major repairs.”

The low prices hurt more than just fishers according to Merill MacInnis, also of Nova Scotia, who told the CBC, “at one time, Nova Scotia boat builders, for example, were going flat out building new boats, because money was good and fishers were investing in the industry. Well now, when you’re just making enough to make your payments, people are not going to do that; they’re going to keep going with what they have, and it’ll have an effect on everybody, whether it be car dealers, boat builders, restaurant owners, whatever. It all has an effect; it all trickles down.”

Of course, limiting the number of lobster fishing licences is a form of a quota, but unfortunately, with low demand and high supply (due to the high volume caught per trap), this quota had become a non-binding constraint. As a result, the price of lobster is not supported above the current low level at the intersection of the supply and demand curves.

The continuation of such low prices has led to calls for the introduction of either new rules that would effectively lower the quota or measures geared toward finding additional demand in other markets at home or abroad, so as to help raise the price of lobster. One way the government has reacted to this situation is via the Atlantic Lobster Sustainability Measures program, which is buying back and retiring about 600 lobster fishing licences. This measure will remove more than 200 000 traps from the water by March 2014.

In 2013, some processing plants, overwhelmed by large catches and hoping to help deal with low prices, imposed their own daily quotas on the volume of lobster per boat they would accept. In other cases, fishers either voluntarily stayed home to reduce supply or agreed to limit catches. Many have called upon the government to buy back even more licences and to impose new rules limiting the daily catch of every licensed boat, a much stronger and clearer quota system.

Notice, by the way, that this is an example of a proposed quota that is probably justified by broader economic and environmental considerations—unlike the New York taxicab quota, which has long since lost any economic rationale. Still, whatever its rationale, the proposed Atlantic Canada lobster quota would work the same way as any other quota.

Once the quota system is established, many boat owners will stop fishing for lobsters. They will realize that rather than operating a boat, it is more profitable to sell or rent their licences to someone else. The value of a licence required to fish for lobsters will easily be worth more than the boat itself.

Quick Review

Quantity controls, or quotas, are government-imposed limits on how much of a good may be bought or sold. The quantity allowed for sale is the quota limit. The government then issues a licence—the right to sell a given quantity of a good under the quota.

When the quota limit is smaller than the equilibrium quantity in an unregulated market, the demand price is higher than the supply price—there is a wedge between them at the quota limit.

This wedge is the quota rent, the earnings that accrue to the licence-holder from ownership of the right to sell the good—whether by actually supplying the good or by renting the licence to someone else. The market rental price of a licence equals the quota rent.

Like price controls, quantity controls create inefficiencies and encourage illegal activity.

Check Your Understanding 4-3

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 4-3

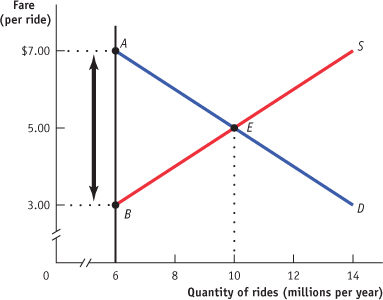

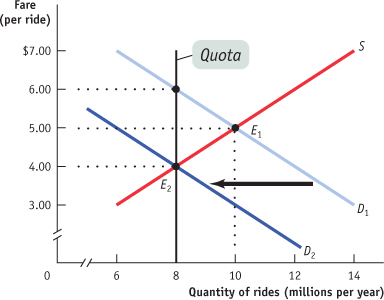

Suppose that the supply and demand for taxi rides is given by Figure 4-7 but the quota is set at 6 million rides instead of 8 million. Find the following and indicate them on Figure 4-7.

The price of a ride

The quota rent

The price of a ride is $7 since the quantity demanded at this price is 6 million: $7 is the demand price of 6 million rides. This is represented by point A in the accompanying figure.

At 6 million rides, the supply price is $3 per ride, represented by point B in the figure. The wedge between the demand price of $7 per ride and the supply price of $3 per ride is the quota rent per ride, $4. This is represented in the figure above by the vertical distance between points A and B.

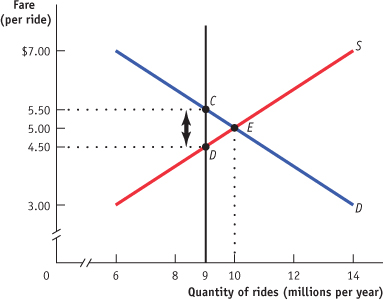

Suppose the quota limit on taxi rides is increased to 9 million. What happens to the quota rent?

At 9 million rides, the demand price is $5.50 per ride, indicated by point C in the accompanying figure, and the supply price is $4.50 per ride, indicated by point D. The quota rent is the difference between the demand price and the supply price: $1.

Assume that the quota limit is 8 million rides. Suppose demand decreases due to a decline in tourism. What is the smallest parallel leftward shift in demand that would result in the quota no longer having an effect on the market? Illustrate your answer using Figure 4-7.

The accompanying figure shows a decrease in demand by 4 million rides, represented by a leftward shift of the demand curve from D1 to D2: at any given price, the quantity demanded falls by 4 million rides. (For example, at a price of $5, the quantity demanded falls from 10 million to 6 million rides per year.) This eliminates the effect of a quota limit of 8 million rides. At point E2, the new market equilibrium, the equilibrium quantity is equal to the quota limit; as a result, the quota has no effect on the market.

Medallion Financial: Cruising Right Along

Back in 1937, before New York City froze its number of taxi medallions, Andrew Murstein’s immigrant grandfather bought his first one for $10. Over time, the grandfather accumulated 500 medallions, which he rented to other drivers. Those 500 taxi medallions became the foundation for Medallion Financial: the company that would eventually pass to Andrew, its current president.

With a market value of over $300 million in mid-2013, Medallion Financial has shifted its major line of business from renting out medallions to financing the purchase of new ones, lending money to those who want to buy a medallion but don’t have the sizable amount of cash required to do so. Murstein believes that he is helping people who, like his Polish immigrant grandfather, want to buy a piece of the American dream.

Andrew Murstein carefully watches the value of a New York City taxi medallion: the more one costs, the more demand there is for loans from Medallion Financial, and the more interest the company makes on the loan. A loan from Medallion Financial is secured by the value of the medallion itself. If the borrower is unable to repay the loan, Medallion Financial takes possession of his or her medallion and resells it to offset the cost of the loan default. As of 2013, the value of a medallion had risen faster than stocks, oil, and gold. Over the past three decades, from 1980 through mid-2013, the value of a medallion rose an average of 6.8% per year, faster than U.S. and Canadian stock market indexes.

But medallion prices can fluctuate dramatically, threatening profits. During periods of a very strong economy, such as 1999 and 2001, the price of New York taxi medallions fell as drivers found jobs in other sectors. When the New York economy tanked in the aftermath of 9/11, the price of a medallion fell to $180 000, its lowest level in 12 years. In 2004, medallion owners were concerned about the impending sale by the New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission of an additional 900 medallions. As Peter Hernandez, a worried New York cabdriver who financed his medallion with a loan from Medallion Financial, said at the time: “If they pump new taxis into the industry, it devalues my medallion. It devalues my daily income, too.”

Yet Murstein has always been optimistic that medallions would hold their value. He believed that a 25% fare increase would offset potential losses in their value caused by the sale of new medallions. In addition, more medallions would mean more loans for his company. As of 2013, Murstein’s optimism had been justified. Because of the financial crisis of 2007–2009, many New York companies cut back the limousine services they ordinarily provided to their employees, forcing them to take taxis instead. As a result, the price of a medallion rose to an astonishing $1 million in early 2013. And investors have noticed the value in Medallion Financial’s line of business: from July 2012 to July 2013, shares of Medallion Financial have rose 31%.

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

How does Medallion Financial benefit from the restriction on the number of New York taxi medallions?

How does Medallion Financial benefit from the restriction on the number of New York taxi medallions?

What will be the effect on Medallion Financial if New York companies resume widespread use of limousine services for their employees? What is the economic motivation that prompts companies to offer this perk to their employees? (Note that it is very difficult and expensive to own a personal car in New York City.)

What will be the effect on Medallion Financial if New York companies resume widespread use of limousine services for their employees? What is the economic motivation that prompts companies to offer this perk to their employees? (Note that it is very difficult and expensive to own a personal car in New York City.)

Predict the effect on Medallion Financial’s business if New York City eliminates restrictions on the number of taxis.

Predict the effect on Medallion Financial’s business if New York City eliminates restrictions on the number of taxis.