5.1 Comparative Advantage and International Trade

Goods and services purchased from other countries are imports; goods and services sold to other countries are exports.

Canada buys auto parts—

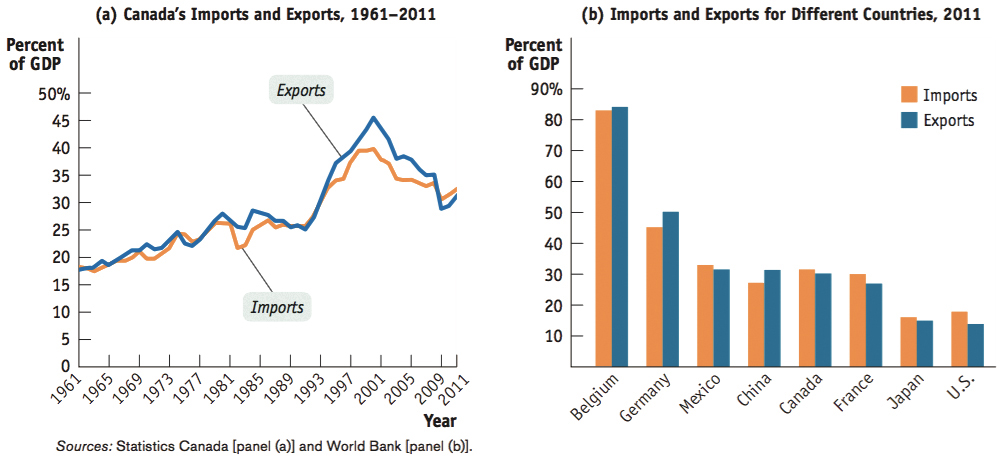

As illustrated by the opening story, imports and exports have taken on an increasingly important role in the Canadian economy. Over the last 50 years, both imports into and exports from Canada have grown faster than the Canadian economy. Panel (a) of Figure 5-1 shows how the values of Canadian imports and exports have grown as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP). Panel (b) shows imports and exports as a percentage of GDP for a number of countries. It shows that foreign trade is more important for some countries than it is for Canada.

Sources: Statistics Canada [panel (a)] and World Bank [panel (b)].

Globalization is the phenomenon of growing economic linkages among countries.

Foreign trade isn’t the only way countries interact economically. In the modern world, investors from one country often invest funds in another nation; many companies are multinational, with subsidiaries operating in several countries; and a growing number of individuals work in a country different from the one in which they were born. The growth of all these forms of economic linkages among countries is often called globalization.

In this chapter, however, we’ll focus mainly on international trade. To understand why international trade occurs and why economists believe it is beneficial to the economy, we will first review the concept of comparative advantage.

Production Possibilities and Comparative Advantage, Revisited

To produce auto parts, any country must use resources—

In some cases, it’s easy to see why the opportunity cost of producing a good is especially low in a given country. Consider, for example, shrimp—

In other cases, matters are a bit less obvious. It’s as easy to produce auto parts in Canada as it is in Mexico, and Mexican auto parts workers are, if anything, less efficient than their Canadian counterparts. But Mexican workers are a lot less productive than Canadian workers in other areas, such as aircraft and chemical production. This means that diverting a Mexican worker into auto parts production reduces output of other goods less than diverting a Canadian worker into auto parts production. That is, the opportunity cost of producing auto parts in Mexico is less than it is in Canada.

So we say that Mexico has a comparative advantage in producing auto parts. Let’s repeat the definition of comparative advantage from Chapter 2: A country has a comparative advantage in producing a good or service if the opportunity cost of producing the good or service is lower for that country than for other countries.

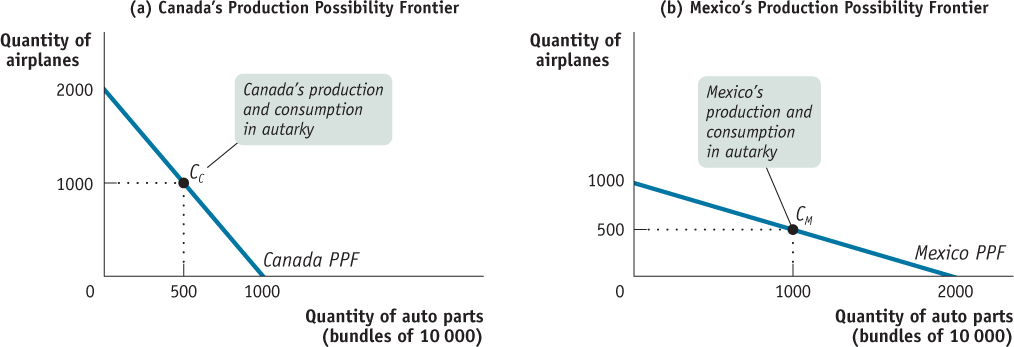

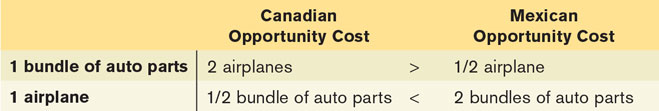

Figure 5-2 provides a hypothetical numerical example of comparative advantage in international trade. We assume that only two goods are produced and consumed, auto parts and airplanes, and that there are only two countries in the world, Canada and Mexico. (In real life, auto parts aren’t worth much without auto bodies to put them in, but let’s set that issue aside). The figure shows hypothetical production possibility frontiers for Canada and Mexico.

The Ricardian model of international trade analyzes international trade under the assumption that opportunity costs are constant.

As in Chapter 2, we simplify the model by assuming that the production possibility frontiers are straight lines, as shown in Figure 2-1, rather than the more realistic bowed-

In Figure 5-2 we have grouped auto parts into bundles of 10 000, so, for example, a country that produces 500 bundles of auto parts is producing 5 million individual auto parts. You can see in the figure that Canada can produce 2000 airplanes if it produces no auto parts, or 1000 bundles of auto parts if it produces no airplanes. Thus, the slope of Canada’s production possibility frontier, or PPF, is –2000/1000 = –2. That is, to produce an additional bundle of auto parts, Canada must forgo the production of 2 airplanes.

Similarly, Mexico can produce 1000 airplanes if it produces no auto parts or 2000 bundles of auto parts if it produces no airplanes. Thus, the slope of Mexico’s PPF is −1000/2000 = −1/2. That is, to produce an additional bundle of auto parts, Mexico must forgo the production of 1/2 an airplane.

Autarky is a situation in which a country does not trade with other countries.

Economists use the term autarky to refer to a situation in which a country does not trade with other countries—

The trade-

As we learned in Chapter 2, each country can do better by engaging in trade than it could by not trading. A country can accomplish this by specializing in the production of the good in which it has a comparative advantage and exporting that good, while importing the good in which it has a comparative disadvantage. Let’s see how this works.

The Gains from International Trade

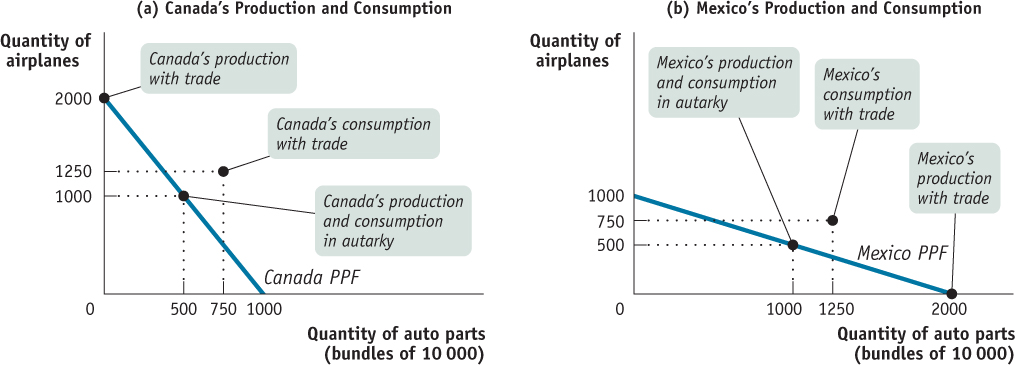

Figure 5-3 illustrates how both countries can gain from specialization and trade, by showing a hypothetical rearrangement of production and consumption that allows each country to consume more of both goods. Again, panel (a) represents Canada and panel (b) represents Mexico. In each panel we indicate again the autarky production and consumption assumed in Figure 5-2. Once trade becomes possible, however, everything changes. With trade, each country can move to producing only the good in which it has a comparative advantage—

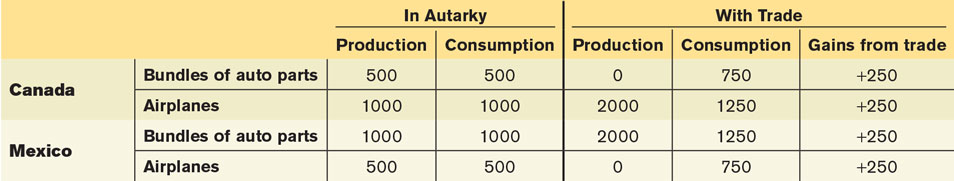

Table 5-2 sums up the changes as a result of trade and shows why both countries can gain. The left part of the table shows the autarky situation, before trade, in which each country must produce the goods it consumes. The right part of the table shows what happens as a result of trade. After trade, Canada specializes in the production of airplanes, producing 2000 airplanes and no auto parts; Mexico specializes in the production of auto parts, producing 2000 bundles of auto parts and no airplanes.

The result is a rise in total world production of both goods. As you can see in Table 5-2, with trade, Canada is able to consume both more airplanes and more auto parts than before, even though it no longer produces auto parts, because it can import parts from Mexico. Mexico can also consume more of both goods, even though it no longer produces airplanes, because it can import airplanes from Canada.

The key to this mutual gain is the fact that trade liberates both countries from self-

Now, in this example we have simply assumed the post-

One requirement that the relative price must satisfy is that no country pays a relative price greater than its opportunity cost of obtaining the good in autarky. That is, Canada won’t pay more than 2 airplanes for each 1 bundle of 10 000 auto parts from Mexico, and Mexico won’t pay more than 2 bundles of 10 000 auto parts for each 1 airplane from Canada. Once this requirement is satisfied, the actual relative price in international trade is determined by supply and demand—

Comparative Advantage versus Absolute Advantage

It’s easy to accept the idea that Vietnam and Thailand have a comparative advantage in shrimp production: they have a tropical climate that’s better suited to shrimp farming than that of Canada, and they have a lot of usable coastal area. So Canada imports shrimp from Vietnam and Thailand. In other cases, however, it may be harder to understand why we import certain goods from abroad.

Canadian imports of auto parts from Mexico is a case in point. There’s nothing about Mexico’s climate or resources that makes it especially good at manufacturing auto parts. In fact, it almost surely takes fewer hours of labour to produce an auto seat or wiring harness in Canada than in Mexico.

Why, then, do we buy Mexican auto parts? Because the gains from trade depend on comparative advantage, not absolute advantage. Yes, it takes less labour to produce a wiring harness in Canada than in Mexico. That is, the productivity of Mexican auto parts workers is less than that of their Canadian counterparts. But what determines comparative advantage is not the amount of resources used to produce a good but the opportunity cost of that good—

Here’s how it works: Mexican workers have low productivity compared with Canadian workers in the auto parts industry. But Mexican workers have even lower productivity compared with Canadian workers in other industries. Because Mexican labour productivity in industries other than auto parts is relatively very low, producing a wiring harness in Mexico, even though it takes a lot of labour, does not require forgoing the production of large quantities of other goods.

In Canada, the opposite is true: very high productivity in other industries (such as high-

Mexico’s comparative advantage in auto parts is reflected in global markets by the wages Mexican workers are paid. That’s because a country’s wage rates, in general, reflect its labour productivity. In countries where labour is highly productive in many industries, employers are willing to pay high wages to attract workers, so competition among employers leads to an overall high wage rate. In countries where labour is less productive, competition for workers is less intense and wage rates are correspondingly lower.

As the accompanying Global Comparison shows, there is indeed a strong relationship between overall levels of productivity and wage rates around the world. Because Mexico has generally low productivity, it has a relatively low wage rate. Low wages, in turn, give Mexico a cost advantage in producing goods where its productivity is only moderately low, like auto parts. As a result, it’s cheaper to produce these parts in Mexico than in Canada.

The kind of trade that takes place between low-

Both fallacies miss the nature of gains from trade: it’s to the advantage of both countries if the poorer, lower-

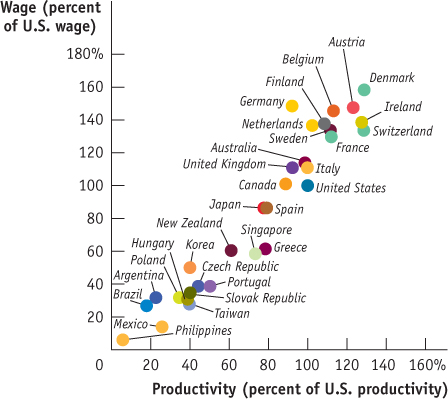

PRODUCTIVITY AND WAGES AROUND THE WORLD

Is it true that both the pauper labour argument and the sweatshop labour argument are fallacies? Yes, it is. The real explanation for low wages in poor countries is low overall productivity.

The graph shows estimates of labour productivity, measured by the value of output (GDP) per worker, and wages, measured by the monthly compensation of the average worker, for several countries in 2009. Both productivity and wages are expressed as percentages of U.S. productivity and wages; for example, productivity and wages in Japan were 79% and 91%, respectively, of their U.S. levels. You can see the strong positive relationship between productivity and wages. The relationship isn’t perfect. For example, Germany has higher wages than its productivity might lead you to expect. But simple comparisons of wages give a misleading sense of labour costs in poor countries: their low-

Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics; International Monetary Fund.

It’s particularly important to understand that buying a good made by someone who is paid much lower wages than most Canadian workers doesn’t necessarily imply that you’re taking advantage of that person. It depends on the alternatives. Because workers in poor countries have low productivity across the board, they are offered low wages whether they produce goods exported to Canada or goods sold in local markets. A job that looks terrible by rich-

International trade that depends on low-

Sources of Comparative Advantage

International trade is driven by comparative advantage, but where does comparative advantage come from? Economists who study international trade have found three main sources of comparative advantage: international differences in climate, international differences in factor endowments, and international differences in technology.

Differences in Climate One key reason the opportunity cost of producing shrimp in Vietnam and Thailand is less than in Canada is that shrimp need warm water—Vietnam has plenty of that, but Canada doesn’t. In general, differences in climate play a significant role in international trade. Tropical countries export tropical products like coffee, sugar, bananas, and shrimp. Countries in the temperate zones export crops like wheat and corn. Some trade is even driven by the difference in seasons between the northern and southern hemispheres: winter deliveries of Chilean grapes and New Zealand apples have become commonplace in North American and European supermarkets.

Differences in Factor Endowments Canada is a major exporter of forest products—lumber and products derived from lumber, like pulp and paper—to the United States. These exports don’t reflect the special skill of Canadian lumberjacks. Canada has a comparative advantage in forest products because its forested area is much greater compared to the size of its labour force than the ratio of forestland to the labour force in the United States.

Forestland, like labour and capital, is a factor of production: an input used to produce goods and services. (Recall from Chapter 2 that the factors of production are land, labour, and capital.) Due to history and geography, the mix of available factors of production differs among countries, providing an important source of comparative advantage. The relationship between comparative advantage and factor availability is found in an influential model of international trade, the Heckscher–Ohlin model, developed by two Swedish economists in the first half of the twentieth century.

Two key concepts in the model are factor abundance and factor intensity. Factor abundance refers to how large a country’s supply of a factor is relative to its supply of other factors. Factor intensity refers to the fact that producers use different ratios of factors of production in the production of different goods. For example, oil refineries use much more capital per worker than clothing factories. Economists use the term factor intensity to describe this difference among goods: oil refining is capital-intensive, because it tends to use a high ratio of capital to labour, but auto seats production is labour-intensive, because it tends to use a high ratio of labour to capital.

The factor intensity of production of a good is a measure of which factor is used in relatively greater quantities than other factors in production.

According to the Heckscher-Ohlin model, a country that has an abundant supply of a factor of production will have a comparative advantage in goods whose production is intensive in that factor. So a country that has a relative abundance of capital will have a comparative advantage in capital-intensive industries such as oil refining, but a country that has a relative abundance of labour will have a comparative advantage in labour-intensive industries such as auto seats production.

According to the Heckscher-Ohlin model, a country has a comparative advantage in a good whose production is intensive in the factors that are abundantly available in that country.

The basic intuition behind this result is simple and based on opportunity cost. The opportunity cost of a given factor—the value that the factor would generate in alternative uses—is low for a country when it is relatively abundant in that factor. Relative to Canada, Mexico has an abundance of low-skilled labour. As a result, the opportunity cost of the production of low-skilled, labour-intensive goods is lower in Mexico than in Canada.

The most dramatic example of the validity of the Heckscher–Ohlin model is world trade in clothing. Clothing production is a labour-intensive activity: it doesn’t take much physical capital, nor does it require a lot of human capital in the form of highly educated workers. So you would expect labour-abundant countries such as China and Bangladesh to have a comparative advantage in clothing production. And they do.

That much international trade is the result of differences in factor endowments helps explain another fact: international specialization of production is often incomplete. That is, a country often maintains some domestic production of a good that it imports. A good example of this is Canada and oil. Saudi Arabia exports oil to Canada because Saudi Arabia has an abundant supply of oil relative to its other factors of production; Canada exports medical devices to Saudi Arabia because it has an abundant supply of expertise in medical technology relative to its other factors of production. But Canada also produces some oil domestically because the size of its domestic oil reserves in Alberta makes it economical to do so.

In our supply and demand analysis in the next section, we’ll consider incomplete specialization by a country to be the norm. We should emphasize, however, that the fact that countries often incompletely specialize does not in any way change the conclusion that there are gains from trade.

Differences in Technology In the 1970s and 1980s, Japan became by far the world’s largest exporter of automobiles, selling large numbers to North America and the rest of the world. Japan’s comparative advantage in automobiles wasn’t the result of climate. Nor can it easily be attributed to differences in factor endowments: aside from a scarcity of land, Japan’s mix of available factors is quite similar to that in other developed countries. Instead, as we discussed in the Chapter 2 Business Case on lean production at Toyota and Boeing, Japan’s comparative advantage in automobiles was based on the superior production techniques developed by its manufacturers, which allowed them to produce more cars with a given amount of labour and capital than their North American or European counterparts.

Japan’s comparative advantage in automobiles was a case of comparative advantage caused by differences in technology—the techniques used in production.

The causes of differences in technology are somewhat mysterious. Sometimes they seem to be based on knowledge accumulated through experience—for example, Switzerland’s comparative advantage in watches reflects a long tradition of watchmaking. Sometimes they are the result of a set of innovations that for some reason occur in one country but not in others. Technological advantage, however, is often transitory. As we also discussed in the Chapter 2 Business Case, by adopting lean production, auto manufacturers in North America have now closed much of the gap in productivity with their Japanese competitors. In addition, a technological advantage can be acquired or supported by government funding for research and development. For instance, government support for nuclear and aerospace industries has helped Canada occupy a niche in the world markets for these products. At any given point in time, however, differences in technology are a major source of comparative advantage.

INCREASING RETURNS TO SCALE AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE

Most analysis of international trade focuses on how differences between countries—differences in climate, factor endowments, and technology—create national comparative advantage. However, economists have also pointed out another reason for international trade: the role of increasing returns to scale.

Production of a good is characterized by increasing returns to scale if the average productivity of labour and other resources used in production rise with the quantity of output. For example, in an industry characterized by increasing returns to scale, increasing output by 10% might require only 8% more labour and 9% more raw materials. Examples of industries with increasing returns to scale include auto manufacturing, oil refining, and the production of jumbo jets, all of which require large outlays of capital. Increasing returns to scale (sometimes also called economies of scale) can give rise to monopoly, a situation in which an industry is composed of only one producer, because it gives large firms a cost advantage over small ones.

But increasing returns to scale can also give rise to international trade. The logic runs as follows: If production of a good is characterized by increasing returns to scale, it makes sense to concentrate production in only a few locations, so each location has a high level of output. But that also means production occurs in only a few countries that export the good to other countries. A commonly cited example is the North American auto industry: although both Canada and the United States produce automobiles and their components, each particular model or component tends to be produced in only one of the two countries and exported to the other.

Increasing returns to scale probably play a large role in the trade in manufactured goods between advanced countries, which is about 25% of the total value of world trade.

SKILL AND COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE

In 1953 U.S. workers were clearly better equipped with machinery than their counterparts in other countries. Most economists at the time thought that America’s comparative advantage lay in capital-intensive goods. But economist Wassily Leontief made a surprising discovery: America’s comparative advantage was in something other than capital-intensive goods. In fact, goods that the United States exported were slightly less capital-intensive than goods the country imported. This discovery came to be known as the Leontief paradox, and it led to a sustained effort to make sense of U.S. trade patterns.

The main resolution of this paradox, it turns out, depends on the definition of capital. U.S. exports aren’t intensive in physical capital—machines and buildings. Instead, they are skill-intensive—that is, they are intensive in human capital. U.S. exporting industries use a substantially higher ratio of highly educated workers to other workers than is found in U.S. industries that compete against imports. For example, one of America’s biggest export sectors is aircraft; the aircraft industry employs large numbers of engineers and other people with graduate degrees relative to the number of manual labourers. Conversely, the United States imports a lot of clothing, which is often produced by workers with little formal education.

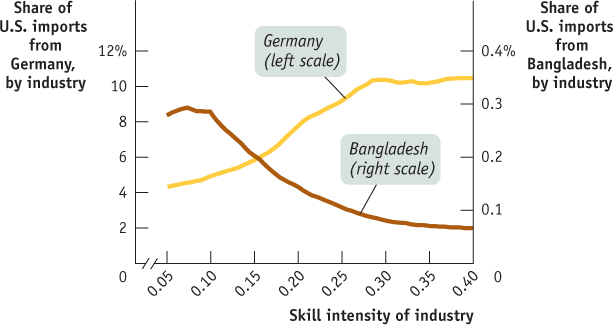

In general, countries with highly educated workforces tend to export skill-intensive goods, while countries with less educated workforces tend to export goods whose production requires little skilled labour. Figure 5-4 illustrates this point by comparing the goods the United States imports from Germany, a country with a highly educated labour force, with the goods the United States imports from Bangladesh, where about half of the adult population is still illiterate. In each country industries are ranked, first, according to how skill-intensive they are. Next, for each industry, we calculate its share of exports to the United States. This allows us to plot, for each country, various industries according to their skill intensity and their share of exports to the United States.

Source: John Romalis, “Factor Proportions and the Structure of Commodity Trade,” American Economic Review 94, no. 1 (2004): 67–97.

In Figure 5-4, the horizontal axis shows a measure of the skill intensity of different industries, and the vertical axes show the share of U.S. imports in each industry coming from Germany (on the left) and Bangladesh (on the right). As you can see, each country’s exports to the United States reflect its skill level. The curve representing Germany slopes upward: the more skill-intensive a German industry is, the higher its share of exports to the United States. In contrast, the curve representing Bangladesh slopes downward: the less skill-intensive a Bangladeshi industry is, the higher its share of exports to the United States.

Quick Review

Imports and exports account for a growing share of the Canadian economy and the economies of many other countries.

The growth of international trade and other international linkages is known as globalization.

International trade is driven by comparative advantage. The Ricardian model of international trade shows that trade between two countries makes both countries better off than they would be in autarky—that is, there are gains from international trade.

The main sources of comparative advantage are international differences in climate, factor endowments, and technology.

The Heckscher-Ohlin model shows how comparative advantage can arise from differences in factor endowments: goods differ in their factor intensity, and countries tend to export goods that are intensive in the factors they have in abundance.

Check Your Understanding 5-1

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 5-1

In Canada, the opportunity cost of 1 tonne of wheat is 50 bicycles. In China, the opportunity cost of 1 bicycle is 0.01 tonne of wheat.

Determine the pattern of comparative advantage.

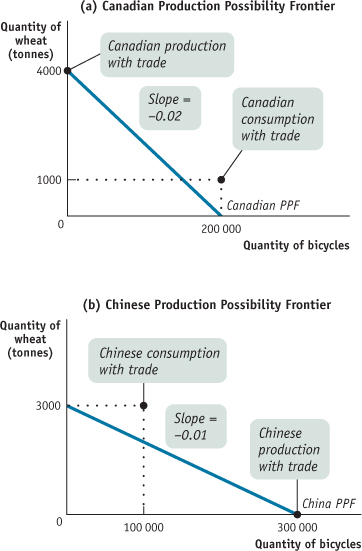

In autarky, Canada can produce 200 000 bicycles if no wheat is produced, and China can produce 3000 tonnes of wheat if no bicycles are produced. Draw each country’s production possibility frontier assuming constant opportunity cost, with tonnes of wheat on the vertical axis and bicycles on the horizontal axis.

With trade, each country specializes its production. Canada consumes 1000 tonnes of wheat and 200 000 bicycles; China consumes 3000 tonnes of wheat and 100 000 bicycles. Indicate the production and consumption points on your diagrams, and use them to explain the gains from trade.

To determine comparative advantage, we must compare the two countries’ opportunity costs for a given good. Take the opportunity cost of 1 tonne of wheat in terms of bicycles. In China, the opportunity cost of 1 bicycle is 0.01 tonne of wheat; so the opportunity cost of 1 tonne of wheat is 1/0.01 bicycles = 100 bicycles. Canada has the comparative advantage in wheat since its opportunity cost in terms of bicycles is 50, a smaller number. Similarly, the opportunity cost in Canada of 1 bicycle in terms of wheat is 1/50 tonne of wheat = 0.02 tonne of wheat. This is greater than 0.01, the Chinese opportunity cost of 1 bicycle in terms of wheat, implying that China has a comparative advantage in bicycles.

Given that Canada can produce 200 000 bicycles if no wheat is produced, it can produce 200 000 bicycles × 0.02 tonne of wheat/bicycle = 4000 tonnes of wheat when no bicycles are produced. Likewise, if China can produce 3000 tonnes of wheat if no bicycles are produced, it can produce 3000 tonnes of wheat × 100 bicycles/tonne of wheat = 300 000 bicycles if no wheat is produced. These points determine the vertical and horizontal intercepts of the Canadian and Chinese production possibility frontiers, as shown in the accompanying diagram.

The diagram shows the production and consumption points of the two countries. Each country is clearly better off with international trade because each now consumes a bundle of the two goods that lies outside its own production possibility frontier, indicating that these bundles were unattainable in autarky.

Explain the following patterns of trade using the Heckscher–Ohlin model.

France exports wine to Canada, and Canada exports lumber to France.

Brazil exports shoes to Canada, and Canada exports shoe-making machinery to Brazil.

According to the Heckscher–Ohlin model, this pattern of trade occurs because Canada has a relatively larger endowment of factors of production, such as human capital and physical capital, that are suited to the production of lumber, but France has a relatively larger endowment of factors of production suited to wine-making, such as vineyards and the human capital of vintners.

According to the Heckscher–Ohlin model, this pattern of trade occurs because Canada has a relatively larger endowment of factors of production, such as human and physical capital, that are suited to making machinery, but Brazil has a relatively larger endowment of factors of production suited to shoe-making, such as unskilled labour and leather.