6.1 The Nature of Macroeconomics

What makes macroeconomics different from microeconomics? The distinguishing feature of macroeconomics is that it focuses on the behaviour of the economy as a whole.

Macroeconomic Questions

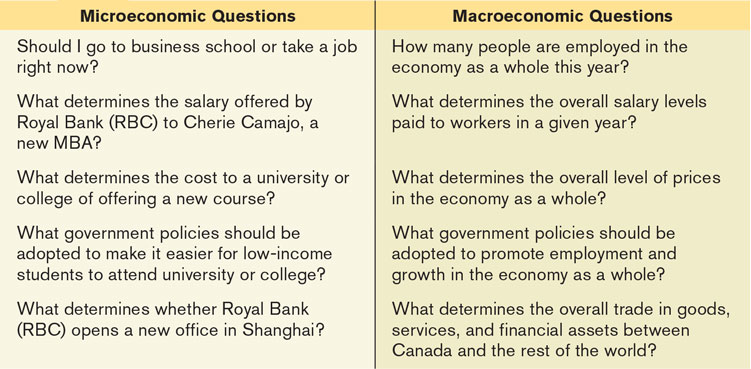

Table 6-1 lists some typical questions that involve economics. A microeconomic version of the question appears on the left paired with a similar macroeconomic question on the right. By comparing the questions, you can begin to get a sense of the difference between microeconomics and macroeconomics.

As these questions illustrate, microeconomics focuses on how decisions are made by individuals and firms and the consequences of those decisions. For example, we use microeconomics to determine how much it would cost a university or college to offer a new course, which includes the instructor’s salary, the cost of class materials, and so on. The school can then decide whether or not to offer the course by weighing the costs and benefits. Macroeconomics, in contrast, examines the overall behaviour of the economy—

You might imagine that macroeconomic questions can be answered simply by adding up microeconomic answers. For example, the model of supply and demand we introduced in Chapter 3 tells us how the equilibrium price of an individual good or service is determined in a competitive market. So you might think that applying supply and demand analysis to every good and service in the economy, then summing the results, is the way to understand the overall level of prices in the economy as a whole.

But that turns out not to be right: although basic concepts such as supply and demand are as essential to macroeconomics as they are to microeconomics, answering macroeconomic questions requires an additional set of tools and an expanded frame of reference.

Macroeconomics: The Whole Is Greater Than the Sum of Its Parts

If you occasionally drive on a highway, you probably know what a rubbernecking traffic jam is and why it is so annoying. Someone pulls over to the side of the road for something minor, such as changing a flat tire, and, pretty soon, a long traffic jam occurs as drivers slow down to take a look. What makes it so annoying is that the length of the traffic jam is greatly out of proportion to the minor event that precipitated it. Because some drivers hit their brakes in order to rubberneck, the drivers behind them must also hit their brakes, those behind them must do the same, and so on. The accumulation of all the individual hitting of brakes eventually leads to a long, wasteful traffic jam as each driver slows down a little bit more than the driver in front of him or her. In other words, each person’s response leads to an amplified response by the next person.

Understanding a rubbernecking traffic jam gives us some insight into one very important way in which macroeconomics is different from microeconomics: many thousands or millions of individual actions compound upon one another to produce an outcome that isn’t simply the sum of those individual actions.

Consider, for example, what macroeconomists call the paradox of thrift: when families and businesses are worried about the possibility of economic hard times, they prepare by cutting their spending. This reduction in spending depresses the economy as consumers spend less and businesses react by laying off workers. As a result, families and businesses may end up worse off than if they hadn’t tried to act responsibly by cutting their spending. This is a paradox because seemingly virtuous behaviour—

Or consider what happens when something causes the quantity of cash circulating through the economy to rise. An individual with more cash on hand is richer. But if everyone has more cash, the long-

A key insight of macroeconomics, then, is that the combined effect of individual decisions can have results that are very different from what any one individual intended, results that are sometimes perverse. The behaviour of the macroeconomy is, indeed, greater than the sum of individual actions and market outcomes.

Macroeconomics: Theory and Policy

To a much greater extent than microeconomists, macroeconomists are concerned with questions about policy, about what the government can do to make macroeconomic performance better. This policy focus was strongly shaped by history, in particular by the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Before the 1930s, economists tended to regard the economy as self-regulating: they believed that problems such as unemployment would be corrected through the working of the invisible hand and that government attempts to improve the economy’s performance would be ineffective at best—and would probably make things worse.

In a self-regulating economy, problems such as unemployment are resolved without government intervention, through the working of the invisible hand.

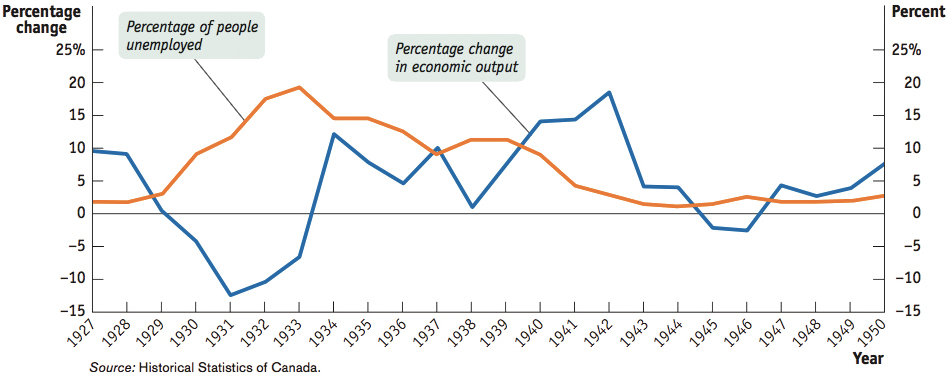

The Great Depression changed all that. The effects of this catastrophe were devastating. From 1929 to 1933, Canada’s real gross domestic product (GDP) fell by more than 30% and unemployment rose enormously (see Figure 6-1). The gross domestic product and the unemployment rate will be discussed in more detail later on; for now you just need to know that a low GDP and a high unemployment rate are bad for the economy. Furthermore, the Depression threatened the political stability of many countries—it is widely believed to have been a major factor in the Nazi takeover of Germany. All of these effects created a demand for action.

Source: Historical Statistics of Canada.

The Depression also led to a major effort on the part of economists to understand economic slumps and find ways to prevent them. In 1936, the British economist John Maynard Keynes (pronounced “canes”) published The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, a book that transformed macroeconomics. According to Keynesian economics, a depressed economy is the result of inadequate spending. In addition, Keynes argued that government intervention can help a depressed economy through monetary policy and fiscal policy. Monetary policy uses the quantity and/or the growth rate of money to affect economic activity. This policy influences the inflation rate, interest rates, exchange rates, and other important short-run economic variables. The Bank of Canada, Canada’s central bank, is responsible for the design and implementation of Canadian monetary policy. It also serves as the bank for large domestic banks and helps manage the (bank) accounts of the federal government. More details about the role and functions of the Bank of Canada will be discussed in Chapters 14 and 15. Fiscal policy uses changes in taxes and government spending to affect overall economic activity. The federal, provincial, and municipal governments also design and implement fiscal policy. Details on how fiscal policy affects economic activity will be discussed in Chapter 13.

According to Keynesian economics, economic slumps are caused by inadequate spending, and they can be mitigated by government intervention.

Monetary policy uses the quantity and/or the growth rate of money to affect economic activity.

Fiscal policy uses changes in taxes and government spending to affect overall economic activity.

In general, Keynes established the idea that managing the economy is a government responsibility. Keynesian ideas continue to have a strong influence on both economic theory and public policy: in 2008 and 2009, the federal government and the Bank of Canada took steps that were clearly Keynesian in spirit to fend off an economic slump, as described in the following Economics in Action.

FENDING OFF DEPRESSION

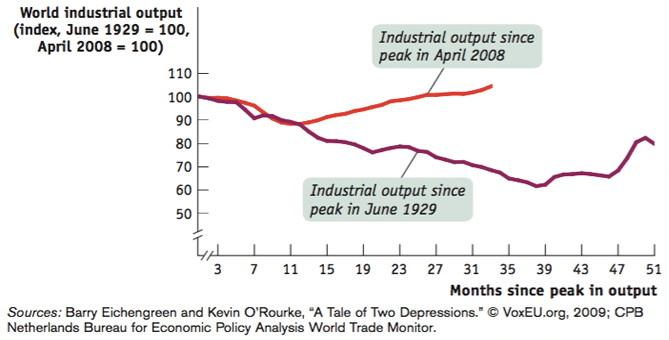

In 2008, the world economy experienced a severe financial crisis that was all too reminiscent of the early days of the Great Depression. Major banks teetered on the edge of collapse; world trade slumped. In the spring of 2009, the economic historians Barry Eichengreen and Kevin O’Rourke, reviewing the available data, pointed out that “globally we are tracking or even doing worse than the Great Depression.”

But the worst did not, in the end, come to pass. Figure 6-2 shows one of Eichengreen and O’Rourke’s measures of economic activity, world industrial production, during the Great Depression and during “the Great Recession,” the now widely used American term for the slump that followed the 2008 financial crisis. During the first year, the two crises were indeed comparable. But this time, fortunately, world production levelled off and turned around. Why?

Sources: Barry Eichengreen and Kevin O’Rourke, “A Tale of Two Depressions.” © VoxEU.org, 2009; CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis World Trade Monitor.

At least part of the answer is that policy-makers responded very differently. During the Great Depression, it was widely argued that the slump should simply be allowed to run its course. Any attempt to mitigate the ongoing catastrophe, declared Joseph Schumpeter—the Austrian-born Harvard economist now famed for his work on innovation—would “leave the work of depression undone.” In the early 1930s, some countries’ monetary authorities actually raised interest rates in the face of the slump, while governments cut spending and raised taxes—actions that, as we’ll see in later chapters, deepened the recession.

In the aftermath of the 2008 crisis, by contrast, interest rates were slashed, and a number of countries, Canada and the United States included, used temporary increases in spending and reductions in taxes in an attempt to sustain spending. Governments also moved to shore up their banks with loans, aid, and guarantees. For example, the federal government rolled out the Economic Action Plan, while the Bank of Canada lowered interest rates to historically low levels to stimulate the economy.

Many of these measures were controversial, to say the least. But most economists believe that by responding actively to the Great Recession—and doing so using the knowledge gained from the study of macroeconomics—governments helped avoid a global economic catastrophe.

Quick Review

Microeconomics focuses on decision-making by individuals and firms and the consequences of the decisions made. Macroeconomics focuses on the overall behaviour of the economy.

The combined effect of individual actions can have unintended consequences and lead to worse or better macroeconomic outcomes for everyone.

Before the 1930s, economists tended to regard the economy as self-regulating. After the Great Depression, Keynesian economics provided the rationale for government intervention through monetary policy and fiscal policy to help a depressed economy.

Check Your Understanding 6-1

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 6-1

Which of the following questions involve microeconomics, and which involve macroeconomics? In each case, explain your answer.

Why did consumers switch to smaller cars in 2008?

Why did overall consumer spending slow down in 2008?

Why did the standard of living rise more rapidly in the first generation after World War II than in the second?

Why have starting salaries for students with geology degrees risen sharply of late?

What determines the choice between rail and road transportation?

Why has salmon gotten cheaper over the past 20 years?

Why did inflation fall in the 1990s?

This is a microeconomic question because it addresses decisions made by consumers about a particular product.

This is a macroeconomic question because it addresses consumer spending in the overall economy.

This is a macroeconomic question because it addresses changes in the overall economy.

This is a microeconomic question because it addresses changes in a particular market, in this case the market for geologists.

This is a microeconomic question because it addresses choices made by consumers and producers about which mode of transportation to use.

This is a microeconomic question because it addresses changes in a particular market.

This is a macroeconomic question because it addresses changes in a measure of the economy’s overall price level.

In 2008, problems in the financial sector led to a drying up of some types of credit around the country: some homebuyers were unable to get mortgages, and some businesses were unable to get loans.

Explain how the drying up of credit can lead to compounding effects throughout the economy and result in an economic slump.

If you believe the economy is self-regulating, what would you advocate that policy-makers do?

If you believe in Keynesian economics, what would you advocate that policy-makers do?

When people can’t get credit to finance their purchases, they will be unable to spend money. This will weaken the economy, and as others see the economy weaken, they will also cut back on their spending in order to save for future bad times. As a result, the credit shortfall will spark a compounding effect through the economy as people cut back their spending, making the economy worse, leading to more cutbacks in spending, and so on.

If you believe the economy is self-regulating, then you would advocate doing nothing in response to the slump.

If you believe in Keynesian economics, you would advocate that policy-makers undertake monetary and fiscal policies to stimulate spending in the economy.