Is World Growth Sustainable?

Earlier in this chapter we described the views of Thomas Malthus, the early-

Sustainable long-

But will this always be the case? Some skeptics have expressed doubt about whether sustainable long-

Natural Resources and Growth, Revisited

In 1972 a group of scientists called The Club of Rome made a big splash with a book titled The Limits to Growth, which argued that long-

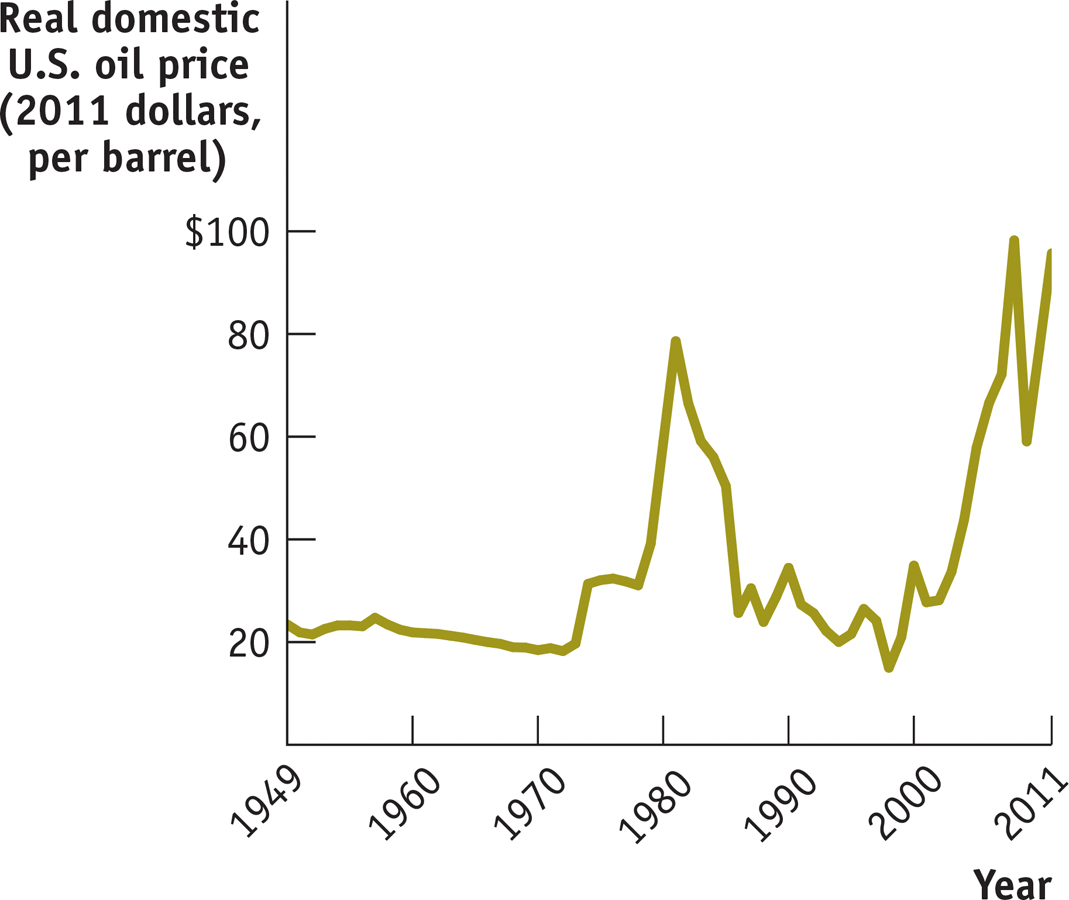

Figure 24-10 shows the real price of oil—

24-10

The Real Price of Oil, 1949–

Differing views about the impact of limited natural resources on long-

How large are the supplies of key natural resources?

How effective will technology be at finding alternatives to natural resources?

Can long-

run economic growth continue in the face of resource scarcity?

It’s mainly up to geologists to answer the first question. Unfortunately, there’s wide disagreement among the experts, especially about the prospects for future oil production. Some analysts believe that there is enough untapped oil in the ground that world oil production can continue to rise for several decades. Others, including a number of oil company executives, believe that the growing difficulty of finding new oil fields will cause oil production to plateau—

The answer to the second question, whether there are alternatives to natural resources, has to come from engineers. There’s no question that there are many alternatives to the natural resources currently being depleted, some of which are already being exploited. Indeed, since around 2005 there have been dramatic developments in energy production, with large amounts of previously unreachable oil and gas extracted through fracking, and with a huge decline in the cost of electricity generated by wind and especially solar power.

The third question, whether economies can continue to grow in the face of resource scarcity, is mainly a question for economists. And most, though not all, economists are optimistic: they believe that modern economies can find ways to work around limits on the supply of natural resources. One reason for this optimism is the fact that resource scarcity leads to high resource prices. These high prices in turn provide strong incentives to conserve the scarce resource and to find alternatives.

For example, after the sharp oil price increases of the 1970s, American consumers turned to smaller, more fuel-

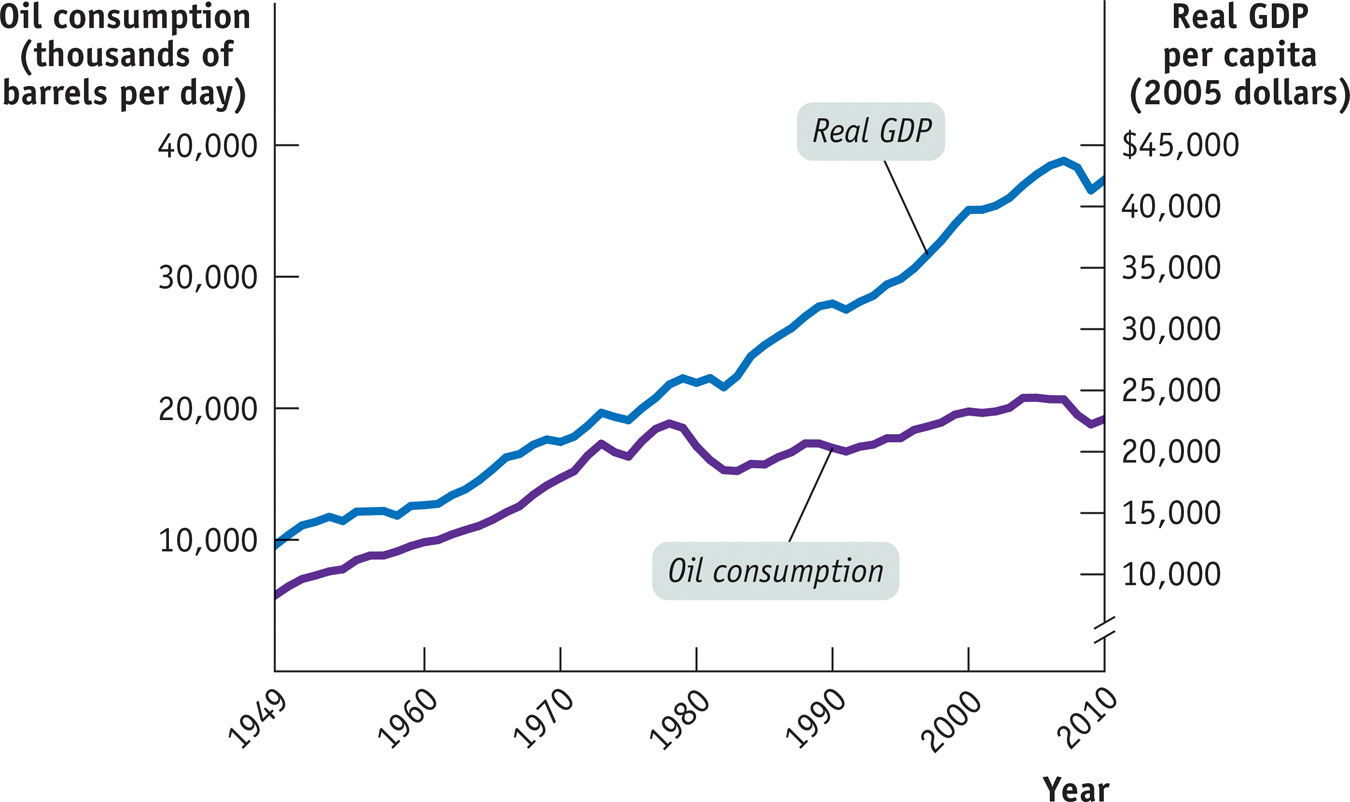

24-11

U.S. Oil Consumption and Growth over Time

This move toward conservation paused after 1990, as low real oil prices encouraged consumers to shift back to gas-

Given such responses to prices, economists generally tend to see resource scarcity as a problem that modern economies handle fairly well, and so not a fundamental limit to long-

Economic Growth and the Environment

Economic growth, other things equal, tends to increase the human impact on the environment. As we saw in this chapter’s opening story, China’s spectacular economic growth has also brought a spectacular increase in air pollution in that nation’s cities.

It’s important to realize, however, that other things aren’t necessarily equal: countries can and do take action to protect their environments. In fact, air and water quality in today’s advanced countries is generally much better than it was a few decades ago. London’s famous “fog”—actually a form of air pollution, which killed 4,000 people during a two-

Despite these past environmental success stories, there is widespread concern today about the environmental impacts of continuing economic growth, reflecting a change in the scale of the problem. Environmental success stories have mainly involved dealing with local impacts of economic growth, such as the effect of widespread car ownership on air quality in the Los Angeles basin. Today, however, we are faced with global environmental issues—

Burning coal and oil releases carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. There is broad scientific consensus that rising levels of carbon dioxide and other gases are causing a greenhouse effect on the Earth, trapping more of the sun’s energy and raising the planet’s overall temperature. And rising temperatures may impose high human and economic costs: rising sea levels may flood coastal areas; changing climate may disrupt agriculture, especially in poor countries; and so on.

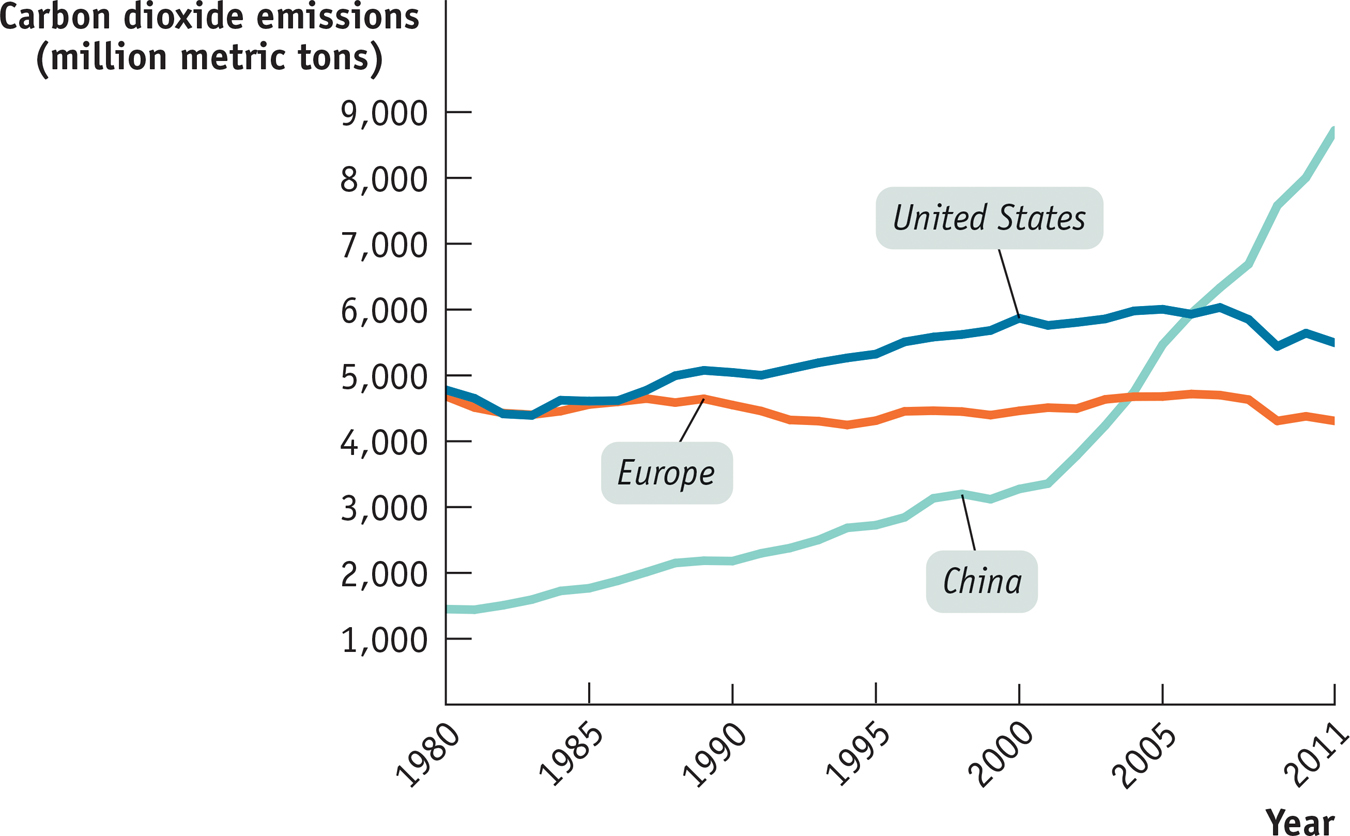

The problem of climate change is clearly linked to economic growth. Figure 24-12 shows carbon dioxide emissions from the United States, Europe, and China since 1980. Historically, the wealthy nations have been responsible for the bulk of these emissions because they have consumed far more energy per person than poorer countries. As China and other emerging economies have grown, however, they have begun to consume much more energy and emit much more carbon dioxide.

24-12

Climate Change and Growth

Is it possible to continue long-

The problem is how to make all of this happen. Unlike resource scarcity, environmental problems don’t automatically provide incentives for changed behavior. Pollution is an example of a negative externality, a cost that individuals or firms impose on others without having to offer compensation. In the absence of government intervention, individuals and firms have no incentive to reduce negative externalities, which is why it took regulation to reduce air pollution in America’s cities. And as Nicholas Stern, the author of an influential report on climate change, put it, greenhouse gas emissions are “the mother of all externalities.”

So there is a broad consensus among economists—

There are also several aspects of the climate change problem that make it much more difficult to deal with than, say, smog in Beijing. One is the problem of taking the long view. The impact of greenhouse gas emissions on the climate is very gradual: carbon dioxide put into the atmosphere today won’t have its full effect on the climate for several generations. As a result, there is the political problem of persuading voters to accept pain today in return for gains that will benefit their children, grandchildren, or even great-

There is also a difficult problem of international burden sharing. As Figure 24-12 shows, today’s rich economies have historically been responsible for most greenhouse gas emissions, but newly emerging economies like China are responsible for most of the recent growth. Inevitably, rich countries are reluctant to pay the price of reducing emissions only to have their efforts frustrated by rapidly growing emissions from new players. On the other hand, countries like China, which are still relatively poor, consider it unfair that they should be expected to bear the burden of protecting an environment threatened by the past actions of rich nations.

The general moral of this story is that it is possible to reconcile long-

!worldview! ECONOMICS in Action: The Cost of Limiting Carbon

The Cost of Limiting Carbon

Over the years several bills have been introduced in Congress that would greatly reduce U.S. emissions of greenhouse gases over the next few decades. By 2014, however, it was clear that given the depth of the U.S. political divide, such bills were unlikely to pass for the foreseeable future. However, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is already required by the Clean Air Act to regulate pollutants that endanger public health, and in 2007 the Supreme Court ruled that carbon dioxide emissions meet that criterion.

So the EPA began a series of steps to limit carbon emissions. First, it set new fuel-

But how would new rules affect the economy? A number of politicians and industry groups were quick to assert that the EPA rules would cripple economic growth. For the most part, however, economists disagreed. The EPA’s own analysis suggested that by 2030 its rules would cost the U.S. economy about $9 billion in today’s dollars each year—

Still, the EPA’s proposed rules would at best make a small dent in the problem of climate change. How much would a program that really deals with the problem cost? In April 2014 the U.N. International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimated that global measures limiting the rise in temperatures to 2 degrees centigrade would impose gradually rising costs, reaching about 5% of output by the year 2100. The impact on the world’s rate of economic growth would, however, be small—

Why this optimism? At a fundamental level, the key insight is that given the right incentives modern economies can find many ways to reduce emissions, ranging from the use of renewable energy sources (which have grown much cheaper in the past few years) to inducing consumers to choose goods with lower environmental impact. Economic growth and environmental damage don’t have to go together.

Quick Review

There’s wide disagreement about whether it is possible to have sustainable long-

run economic growth . However, economists generally believe that modern economies can find ways to alleviate limits to growth from natural resource scarcity through the price response that promotes conservation and the creation of alternatives.Overcoming the limits to growth arising from environmental degradation is more difficult because it requires effective government intervention. Limiting the emission of greenhouse gases would require only a modest reduction in the growth rate.

There is broad consensus that government action to address climate change and greenhouse gases should be in the form of market-

based incentives, like a carbon tax or a cap and trade system. It will also require rich and poor countries to come to some agreement on how the cost of emissions reductions will be shared.

24-5

Question 9.13

Are economists typically more concerned about the limits to growth imposed by environmental degradation or those imposed by resource scarcity? Explain, noting the role of negative externalities in your answer.

Economists are typically more concerned about environmental degradation than resource scarcity. The reason is that in modern economies the price response tends to alleviate the limits imposed by resource scarcity through conservation and the development of alternatives. However, because environmental degradation involves a negative externality—a cost imposed by individuals or firms on others without the requirement to pay compensation—effective government intervention is required to address it. As a result, economists are more concerned about the limits to growth imposed by environmental degradation because a market response would be inadequate.

Question 9.14

What is the link between greenhouse gas emissions and growth? What is the expected effect on growth from emissions reduction? Why is international burden sharing of greenhouse gas emissions reduction a contentious problem?

Growth increases a country’s greenhouse gas emissions. The current best estimates are that a large reduction in emissions will result in only a modest reduction in growth. The international burden sharing of greenhouse gas emissions reduction is contentious because rich countries are reluctant to pay the costs of reducing their emissions only to see newly emerging countries like China rapidly increase their emissions. Yet most of the current accumulation of gases is due to the past actions of rich countries. Poorer countries like China are equally reluctant to sacrifice their growth to pay for the past actions of rich countries.

Solutions appear at back of book.

How Boeing Got Better

When we think about innovation and technological progress, we tend to focus on the big, dramatic changes: cars replacing horses and buggies, electric lightbulbs replacing gaslights, computers replacing adding machines and typewriters. A lot of progress, however, is incremental and almost invisible to most people—

The Boeing 707, introduced in 1957, was the first commercially successful jetliner, and for a number of years it ruled the skies. When the Beatles made their famous 1964 arrival in America, it was a 707 that brought them there. So what did the 707 look like? What’s striking about it, from a modern perspective, is how ordinary it appears. Basically, it looks like a jet airliner. If you walked past one today, and nobody told you it was an antique, you probably wouldn’t notice; 50-

Furthermore, the visible performance of modern jets, like the Boeing 777 or the even more advanced 787, isn’t that much better than those of the old 707. They only fly slightly faster; once you take extra security procedures and air traffic delays into account, traveling from London to New York probably takes more time now than it did in 1964. It’s nice to have a selection of movies (although there never does seem to be anything you want to watch), and business-

Yet Boeing’s modern jets (and those of its main competitor, Airbus) are vastly more efficient than jets half a century ago—

The answer is, things passengers can’t see. Most important, there has been a drastic improvement in fuel efficiency, with modern planes using less than a third as much fuel per passenger-

The moral is that the technological progress that drives growth is much broader and more powerful than meets the eye. Even when things look more or less the same, there is often enormous change beneath the surface.

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

Question 9.15

A modern jet airliner does pretty much the same thing as an airliner from the 1960s: it gets you there from here, in about the same time. Where’s the technological progress?

A modern jet airliner does pretty much the same thing as an airliner from the 1960s: it gets you there from here, in about the same time. Where’s the technological progress?Question 9.16

Do scientific advances play any role in the progress we’ve described? Explain.

Do scientific advances play any role in the progress we’ve described? Explain.Question 9.17

Some travelers complain that the flight experience has gone downhill. Does this refute the claim of technological progress?

Some travelers complain that the flight experience has gone downhill. Does this refute the claim of technological progress?