The Federal Reserve System

A central bank is an institution that oversees and regulates the banking system and controls the monetary base.

Who’s in charge of ensuring that banks maintain enough reserves? Who decides how large the monetary base will be? The answer, in the United States, is an institution known as the Federal Reserve (or, informally, as “the Fed”). The Federal Reserve is a central bank—an institution that oversees and regulates the banking system and controls the monetary base. Other central banks include the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan, and the European Central Bank, or ECB. The ECB acts as a common central bank for 18 European countries: Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain. The world’s oldest central bank, by the way, is Sweden’s Sveriges Riksbank, which awards the Nobel Prize in economics.

The Structure of the Fed

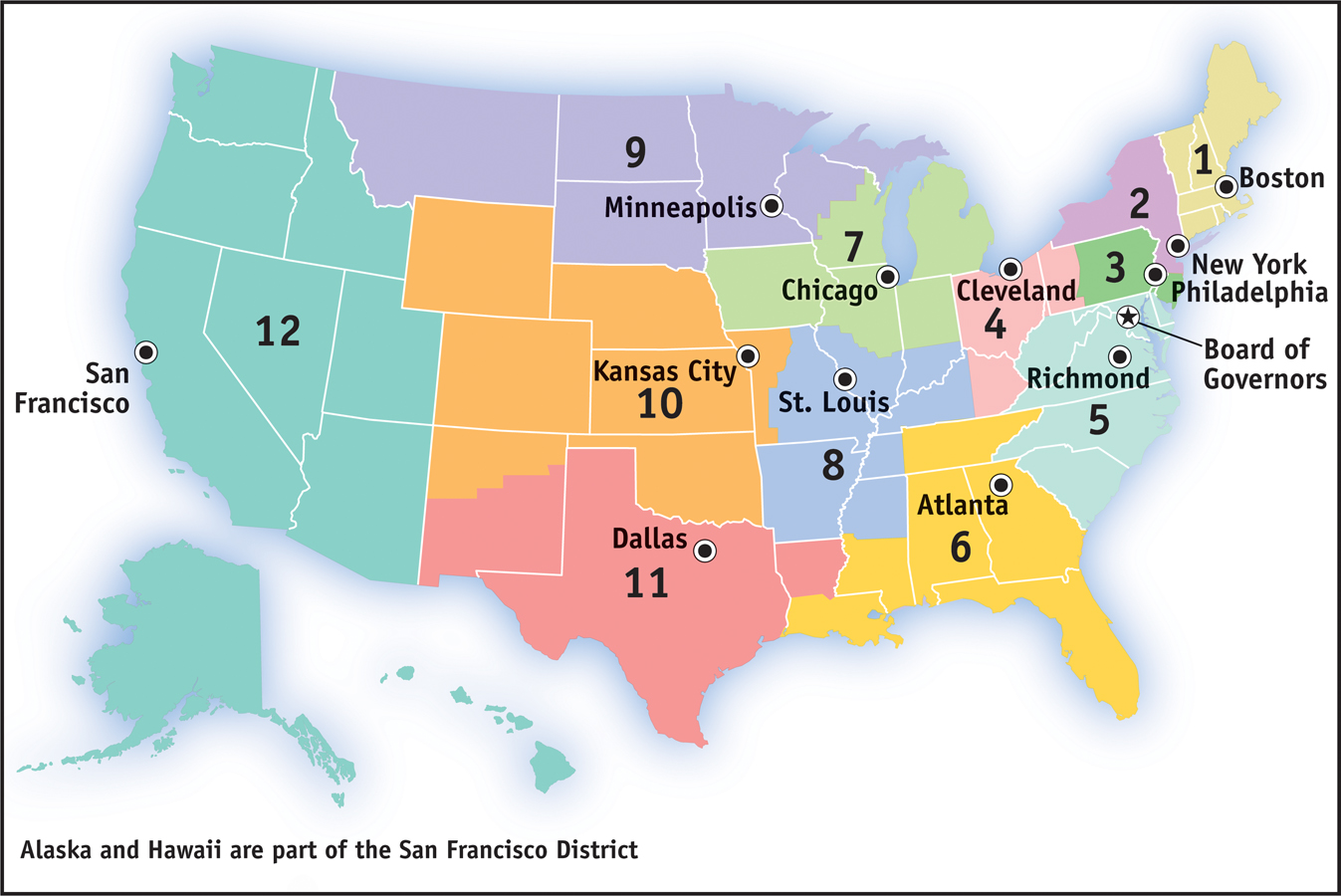

The legal status of the Fed, which was created in 1913, is unusual: it is not exactly part of the U.S. government, but it is not really a private institution either. Strictly speaking, the Federal Reserve system consists of two parts: the Board of Governors and the 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks.

The Board of Governors, which oversees the entire system from its offices in Washington, D.C., is constituted like a government agency: its seven members are appointed by the president and must be approved by the Senate. However, they are appointed for 14-

The 12 Federal Reserve Banks each serve a region of the country, providing various banking and supervisory services. One of their jobs, for example, is to audit the books of private-

29-6

The Federal Reserve System

Decisions about monetary policy are made by the Federal Open Market Committee, which consists of the Board of Governors plus five of the regional bank presidents. The president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York is always on the committee, and the other four seats rotate among the 11 other regional bank presidents. The chairman of the Board of Governors normally also serves as the chairman of the Open Market Committee.

The effect of this complex structure is to create an institution that is ultimately accountable to the voting public because the Board of Governors is chosen by the president and confirmed by the Senate, all of whom are themselves elected officials. But the long terms served by board members, as well as the indirectness of their appointment process, largely insulate them from short-

What the Fed Does: Reserve Requirements and the Discount Rate

The Fed has three main policy tools at its disposal: reserve requirements, the discount rate, and, most importantly, open-

In our discussion of bank runs, we noted that the Fed sets a minimum reserve ratio requirement, currently equal to 10% for checkable bank deposits. Banks that fail to maintain at least the required reserve ratio on average over a two-

The federal funds market allows banks that fall short of the reserve requirement to borrow funds from banks with excess reserves.

What does a bank do if it looks as if it has insufficient reserves to meet the Fed’s reserve requirement? Normally, it borrows additional reserves from other banks via the federal funds market, a financial market that allows banks that fall short of the reserve requirement to borrow reserves (usually just overnight) from banks that are holding excess reserves. The interest rate in this market is determined by supply and demand—

The federal funds rate is the interest rate determined in the federal funds market.

The discount rate is the rate of interest the Fed charges on loans to banks.

Alternatively, banks in need of reserves can borrow from the Fed itself via the discount window. The discount rate is the rate of interest the Fed charges on those loans. Normally, the discount rate is set 1 percentage point above the federal funds rate in order to discourage banks from turning to the Fed when they are in need of reserves. Beginning in the fall of 2007, however, the Fed reduced the spread between the federal funds rate and the discount rate as part of its response to an ongoing financial crisis, described in the upcoming Economics in Action. As a result, by the spring of 2008 the discount rate was only 0.25 percentage point above the federal funds rate. And in the summer of 2014 the discount rate was still only 0.65 percentage point above the federal funds rate.

In order to alter the money supply, the Fed can change reserve requirements, the discount rate, or both. If the Fed reduces reserve requirements, banks will lend a larger percentage of their deposits, leading to more loans and an increase in the money supply via the money multiplier. Alternatively, if the Fed increases reserve requirements, banks are forced to reduce their lending, leading to a fall in the money supply via the money multiplier.

If the Fed reduces the spread between the discount rate and the federal funds rate, the cost to banks of being short of reserves falls; banks respond by increasing their lending, and the money supply increases via the money multiplier. If the Fed increases the spread between the discount rate and the federal funds rate, bank lending falls—

Under current practice, however, the Fed doesn’t use changes in reserve requirements to actively manage the money supply. The last significant change in reserve requirements was in 1992. The Fed normally doesn’t use the discount rate either, although, as we mentioned earlier, there was a temporary surge in lending through the discount window beginning in 2007 in response to a financial crisis. Ordinarily, monetary policy is conducted almost exclusively using the Fed’s third policy tool: open-

Open-Market Operations

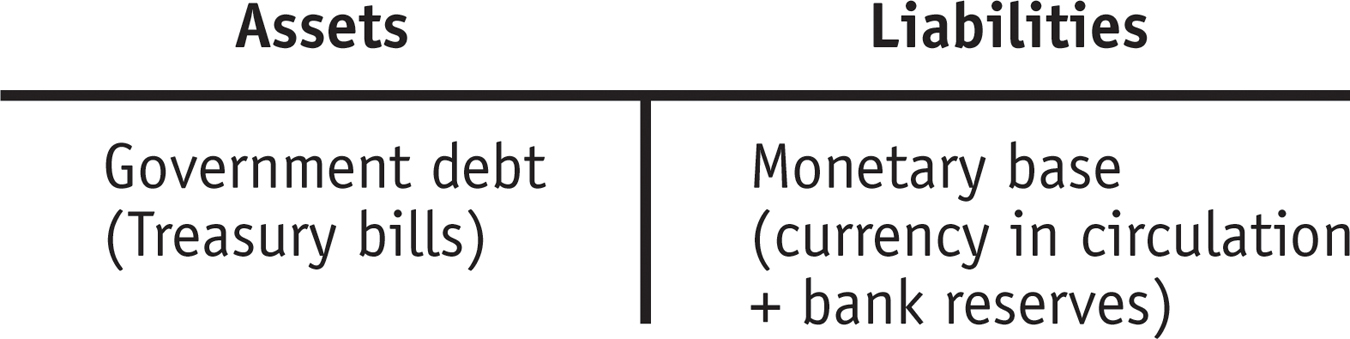

Like the banks it oversees, the Federal Reserve has assets and liabilities. The Fed’s assets normally consist of holdings of debt issued by the U.S. government, mainly short-

29-7

The Federal Reserve’s Assets and Liabilities

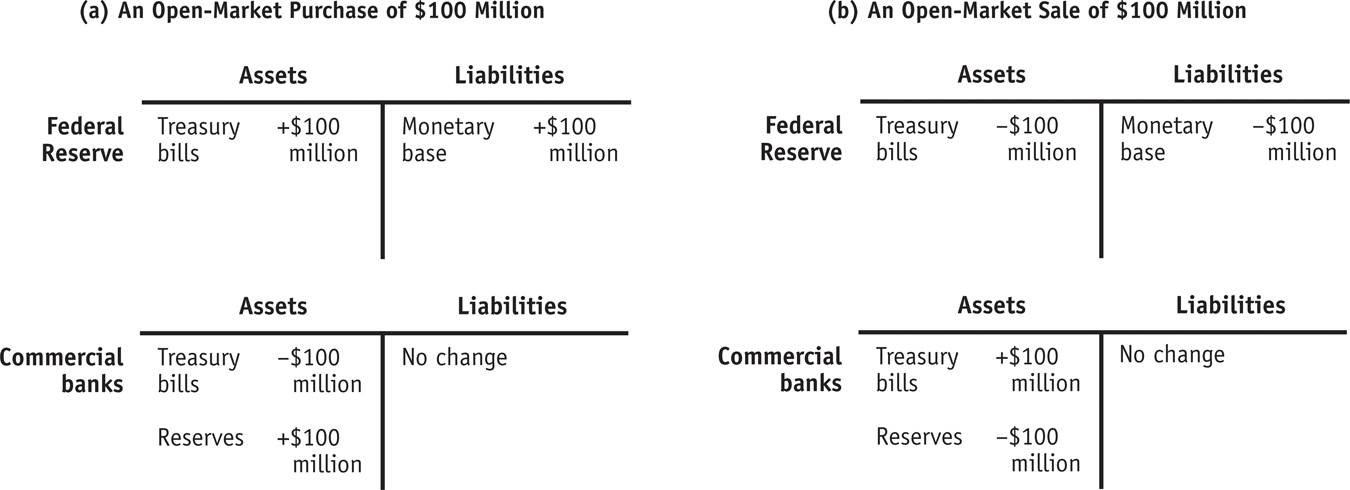

An open-

In an open-

The two panels of Figure 29-8 show the changes in the financial position of both the Fed and commercial banks that result from open-

29-8

Open-

You might wonder where the Fed gets the funds to purchase U.S. Treasury bills from banks. The answer is that it simply creates them with a stroke of the pen—

The change in bank reserves caused by an open-

Who Gets the Interest on the Fed’s Assets?

As we’ve just learned, the Fed owns a lot of assets—

The answer is, you do—

We can now finish the chapter’s opening story—

Meanwhile, the Fed decides on the size of the monetary base based on economic considerations—

Economists often say, loosely, that the Fed controls the money supply—

The European Central Bank

As we noted earlier, the Fed is only one of a number of central banks around the world, and it’s much younger than Sweden’s Sveriges Riksbank and Britain’s Bank of England. In general, other central banks operate in much the same way as the Fed. That’s especially true of the only other central bank that rivals the Fed in terms of importance to the world economy: the European Central Bank.

The European Central Bank, known as the ECB, was created in January 1999 when 11 European nations abandoned their national currencies and adopted the euro as their common currency and placed their joint monetary policy in the ECB’s hands. (Seven more countries have joined since 1999.) The ECB instantly became an extremely important institution: although no single European nation has an economy anywhere near as large as that of the United States, the combined economies of the eurozone, the group of countries that have adopted the euro as their currency, are roughly as big as the U.S. economy. As a result, the ECB and the Fed are the two giants of the monetary world.

Like the Fed, the ECB has a special status: it’s not a private institution, but it’s not exactly a government agency either. In fact, it can’t be a government agency because there is no pan-

First of all, the ECB, which is located in the German city of Frankfurt, isn’t really the counterpart of the whole Federal Reserve system: it’s the equivalent of the Board of Governors in Washington. The European counterparts of the regional Federal Reserve Banks are Europe’s national central banks: the Bank of France, the Bank of Italy, and so on. Until 1999, each of these national banks was its country’s equivalent to the Fed. For example, the Bank of France controlled the French monetary base.

Today these national banks, like regional Feds, provide various financial services to local banks and businesses and conduct open-

In the eurozone, each country chooses who runs its own national central bank. The ECB’s Executive Board is the counterpart of the Fed’s Board of Governors; its members are chosen by unanimous consent of the eurozone national governments. The counterpart of the Federal Open Market Committee is the ECB’s Governing Council. Just as the Fed’s Open Market Committee consists of the Board of Governors plus a rotating group of regional Fed presidents, the ECB’s Governing Council consists of the Executive Board plus the heads of the national central banks.

Like the Fed, the ECB is ultimately answerable to voters, but given the fragmentation of political forces across national boundaries, it appears to be even more insulated than the Fed from short-

!worldview! ECONOMICS in Action: The Fed’s Balance Sheet, Normal and Abnormal

The Fed’s Balance Sheet, Normal and Abnormal

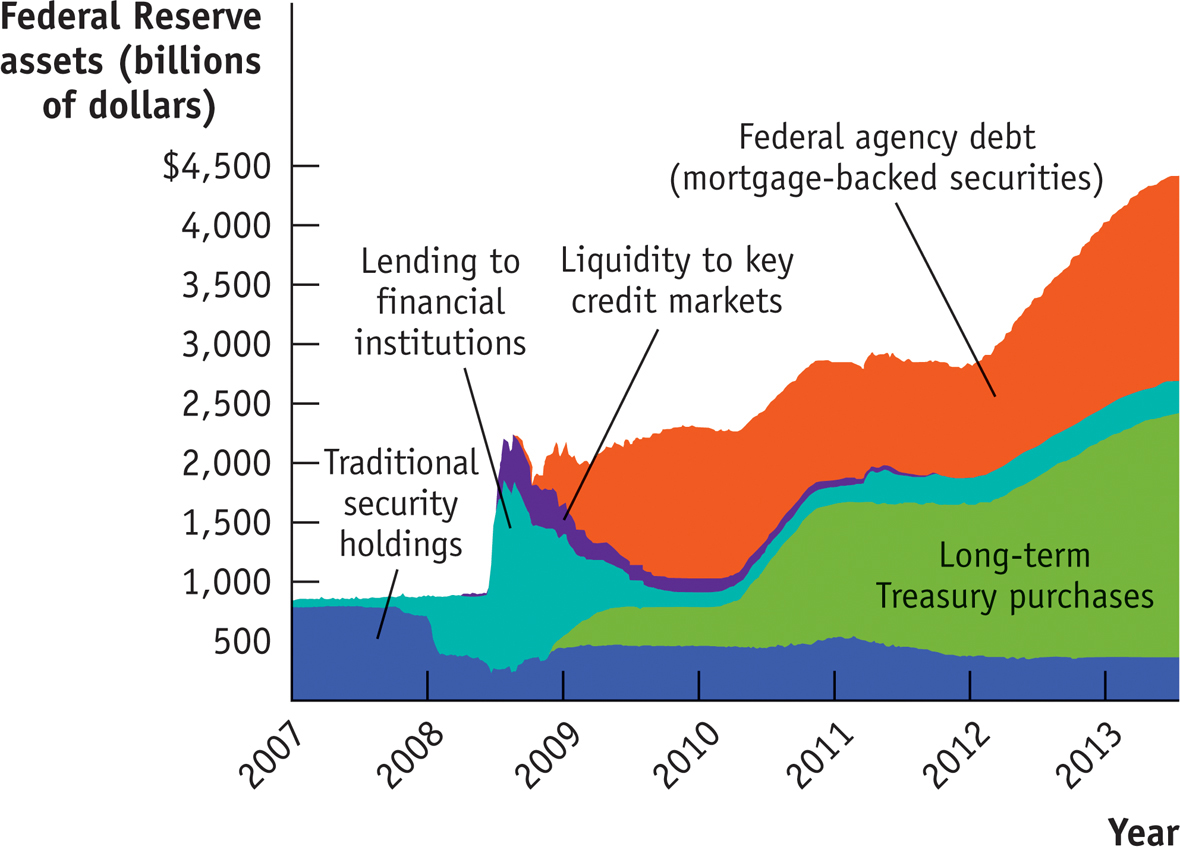

Figure 14-

But in late 2007 it became painfully clear that we were no longer in normal times. The source of the turmoil was the bursting of a huge housing bubble, described in Chapter 25, which led to massive losses for financial institutions that had made mortgage loans or held mortgage-

As we’ll describe in more detail in the next section, not only standard deposit-

For example, in 2008, many investors became worried about the health of Bear Stearns, a Wall Street nondepository financial institution that engaged in complex financial deals, buying and selling financial assets with borrowed funds. When confidence in Bear Stearns dried up, the firm found itself unable to raise the funds it needed to deliver on its end of these deals and it quickly spiraled into collapse.

The Fed sprang into action to contain what was becoming a meltdown across the entire financial sector. It greatly expanded its discount window—

29-9

The Federal Reserve’s Assets

Examining Figure 29-9, we see that starting in mid-

As the crisis subsided in late 2009, the Fed didn’t return to its traditional asset holdings. Instead, it shifted into long-

Quick Review

The Federal Reserve is America’s central bank, overseeing banking and making monetary policy.

The Fed sets the required reserve ratio. Banks borrow and lend reserves in the federal funds market. The interest rate determined in this market is the federal funds rate. Banks can also borrow from the Fed at the discount rate.

Although the Fed can change reserve requirements or the discount rate, in practice, monetary policy is conducted using open-

market operations .An open-

market purchase of Treasury bills increases the monetary base and therefore the money supply. An open- market sale reduces the monetary base and the money supply.

29-4

Question 14.8

Assume that any money lent by a bank is always deposited back in the banking system as a checkable deposit and that the reserve ratio is 10%. Trace out the effects of a $100 million open-

market purchase of U.S. Treasury bills by the Fed on the value of checkable bank deposits. What is the size of the money multiplier? An open-market purchase of $100 million by the Fed increases banks’ reserves by $100 million as the Fed credits their accounts with additional reserves. In other words, this open-market purchase increases the monetary base (currency in circulation plus bank reserves) by $100 million. Banks lend out the additional $100 million. Whoever borrows the money puts it back into the banking system in the form of deposits. Of these deposits, banks lend out $100 million × (1 − rr) = $100 million × 0.9 = $90 million. Whoever borrows the money deposits it back into the banking system. And banks lend out $90 million × 0.9 = $81 million, and so on. As a result, bank deposits increase by $100 million + $90 million + $81 million + . . . = $100 million/rr = $100 million/0.1 = $1,000 million = $1 billion. Since in this simplified example all money lent out is deposited back into the banking system, there is no increase of currency in circulation, so the increase in bank deposits is equal to the increase in the money supply. In other words, the money supply increases by $1 billion. This is greater than the increase in the monetary base by a factor of 10: in this simplified model in which deposits are the only component of the money supply and in which banks hold no excess reserves, the money multiplier is 1/rr = 10.

Solution appears at back of book.