The Crisis in American Banking in the Early Twentieth Century

The creation of the Federal Reserve system in 1913 marked the beginning of the modern era of American banking. From 1864 until 1913, American banking was dominated by a federally regulated system of national banks. They alone were allowed to issue currency, and the currency notes they issued were printed by the federal government with uniform size and design. How much currency a national bank could issue depended on its capital. Although this system was an improvement on the earlier period in which banks issued their own notes with no uniformity and virtually no regulation, the national banking regime still suffered numerous bank failures and major financial crises—

The main problem afflicting the system was that the money supply was not sufficiently responsive: it was difficult to shift currency around the country to respond quickly to local economic changes. (In particular, there was often a tug-

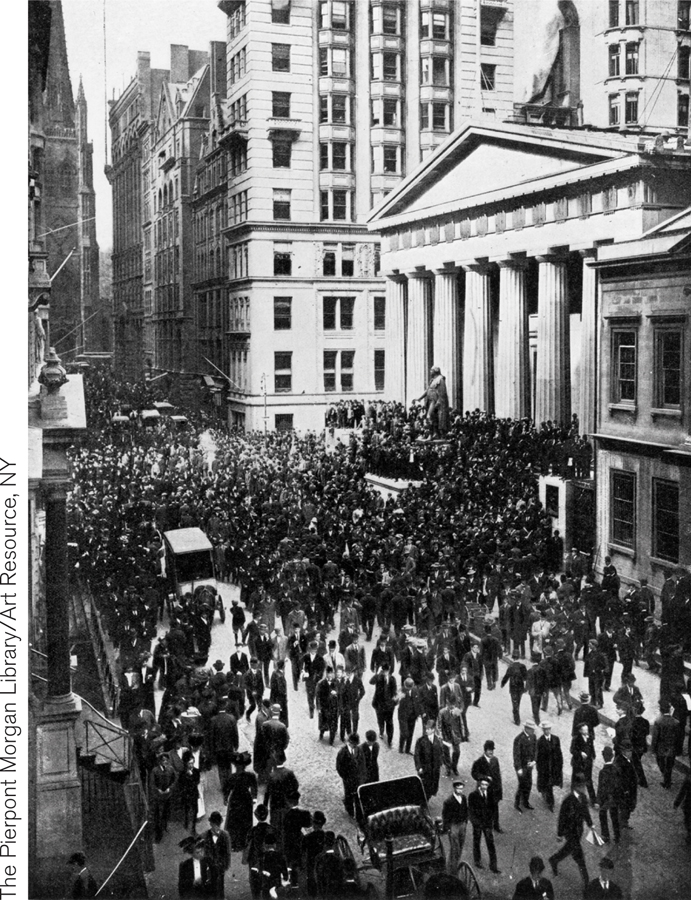

However, the cause of the Panic of 1907 was different from those of previous crises; in fact, its cause was eerily similar to the roots of the 2008 crisis. Ground zero of the 1907 panic was New York City, but the consequences devastated the entire country, leading to a deep four-

The crisis originated in institutions in New York known as trusts, bank-

However, as the American economy boomed during the first decade of the twentieth century, trusts began speculating in real estate and the stock market, areas of speculation forbidden to national banks. Less regulated than national banks, trusts were able to pay their depositors higher returns. Yet trusts took a free ride on national banks’ reputation for soundness, with depositors considering them equally safe. As a result, trusts grew rapidly: by 1907, the total assets of trusts in New York City were as large as those of national banks. Meanwhile, the trusts declined to join the New York Clearinghouse, a consortium of New York City national banks that guaranteed one anothers’ soundness; that would have required the trusts to hold higher cash reserves, reducing their profits.

The Panic of 1907 began with the failure of the Knickerbocker Trust, a large New York City trust that failed when it suffered massive losses in unsuccessful stock market speculation. Quickly, other New York trusts came under pressure, and frightened depositors began queuing in long lines to withdraw their funds. The New York Clearinghouse declined to step in and lend to the trusts, and even healthy trusts came under serious assault. Within two days, a dozen major trusts had gone under. Credit markets froze, and the stock market fell dramatically as stock traders were unable to get credit to finance their trades and business confidence evaporated.

Fortunately, New York City’s wealthiest man, the banker J. P. Morgan, quickly stepped in to stop the panic. Understanding that the crisis was spreading and would soon engulf healthy institutions, trusts and banks alike, he worked with other bankers, wealthy men such as John D. Rockefeller, and the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury to shore up the reserves of banks and trusts so they could withstand the onslaught of withdrawals. Once people were assured that they could withdraw their money, the panic ceased. Although the panic itself lasted little more than a week, it and the stock market collapse decimated the economy. A four-

Responding to Banking Crises: The Creation of the Federal Reserve

Concerns over the frequency of banking crises and the unprecedented role of J. P. Morgan in saving the financial system prompted the federal government to initiate banking reform. In 1913 the national banking system was eliminated and the Federal Reserve system was created as a way to compel all deposit-

Although the new regime standardized and centralized the holding of bank reserves, it did not eliminate the potential for bank runs because banks’ reserves were still less than the total value of their deposits. The potential for more bank runs became a reality during the Great Depression. Plunging commodity prices hit American farmers particularly hard, precipitating a series of bank runs in 1930, 1931, and 1933, each of which started at midwestern banks and then spread throughout the country.

After the failure of a particularly large bank in 1930, federal officials realized that the economy-

As we noted earlier, during the catastrophic bank run of 1933, the new president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, was inaugurated. He immediately declared a “bank holiday,” closing all banks until regulators could get a handle on the problem.

In March 1933, emergency measures were adopted that gave the RFC extraordinary powers to stabilize and restructure the banking industry by providing capital to banks through either loans or outright purchases of bank shares. With the new rules, regulators closed nonviable banks and recapitalized viable ones by allowing the RFC to buy preferred shares in banks (shares that gave the U.S. government more rights than regular shareholders) and by greatly expanding banks’ ability to borrow from the Federal Reserve. By 1933, the RFC had invested over $16.2 billion (2010 dollars) in bank capital—

A commercial bank accepts deposits and is covered by deposit insurance.

An investment bank trades in financial assets and is not covered by deposit insurance.

Economic historians uniformly agree that the banking crises of the early 1930s greatly exacerbated the severity of the Great Depression, rendering monetary policy ineffective as the banking sector broke down and currency, withdrawn from banks and stashed under beds, reduced the money supply.

Although the powerful actions of the RFC stabilized the banking industry, new legislation was needed to prevent future banking crises. The Glass-

Regulation Q prevented commercial banks from paying interest on checking accounts in the belief that this would promote unhealthy competition between banks. In addition, investment banks were much more lightly regulated than commercial banks. The most important measure for the prevention of bank runs, however, was the adoption of federal deposit insurance (with an original limit of $2,500 per deposit).

These measures were clearly successful, and the United States enjoyed a long period of financial and banking stability. As memories of the bad old days dimmed, Depression-

The Savings and Loan Crisis of the 1980s

A savings and loan (thrift) is another type of deposit-

Along with banks, the banking industry also included savings and loans (also called S&Ls or thrifts), institutions designed to accept savings and turn them into long-

In order to improve S&Ls’ competitive position vis-

Unfortunately, during the late 1970s and early 1980s, political interference from Congress kept insolvent S&Ls open when a bank in a comparable situation would have been quickly shut down by bank regulators. By the early 1980s, a large number of S&Ls had failed. Because accounts were covered by federal deposit insurance, the liabilities of a failed S&L were now liabilities of the federal government, and depositors had to be paid from taxpayer funds. From 1986 through 1995, the federal government closed over 1,000 failed S&Ls, costing U.S. taxpayers over $124 billion.

In a classic case of shutting the barn door after the horse has escaped, in 1989 Congress put in place comprehensive oversight of S&L activities. It also empowered Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to take over much of the home mortgage lending previously done by S&Ls. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are quasi-

Back to the Future: The Financial Crisis of 2008

The financial crisis of 2008 shared features of previous crises. Like the Panic of 1907 and the S&L crisis, it involved institutions that were not as strictly regulated as deposit-

In addition, by the late 1990s, advances in technology and financial innovation had created yet another systemic weakness that played a central role in 2008. The story of Long-

A financial institution engages in leverage when it finances its investments with borrowed funds.

Long-

LTCM was also heavily involved in derivatives, complex financial instruments that are constructed—

However, LTCM’s computer models hadn’t factored in a series of financial crises in Asia and in Russia during 1997 and 1998. Through its large borrowing, LTCM had become such a big player in global financial markets that attempts to sell its assets depressed the prices of what it was trying to sell. As the markets fell around the world and LTCM’s panic-

The balance sheet effect is the reduction in a firm’s net worth due to falling asset prices.

The Federal Reserve realized that allowing LTCM’s remaining assets to be sold at panic-

A vicious cycle of deleveraging takes place when asset sales to cover losses produce negative balance sheet effects on other firms and force creditors to call in their loans, forcing sales of more assets and causing further declines in asset prices.

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York arranged a $3.625 billion bailout of LTCM in 1998, in which other private institutions took on shares of LTCM’s assets and obligations, liquidated them in an orderly manner, and eventually turned a small profit. Quick action by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York prevented LTCM from sparking a contagion, yet virtually all of LTCM’s investors were wiped out.

Subprime Lending and the Housing Bubble After the LTCM crisis, U.S. financial markets stabilized. They remained more or less stable even as stock prices fell sharply from 2000 to 2002 and the U.S. economy went into recession. During the recovery from the 2001 recession, however, the seeds for another financial crisis were planted.

The story begins with low interest rates: by 2003, U.S. interest rates were at historically low levels, partly because of Federal Reserve policy and partly because of large inflows of capital from other countries, especially China. These low interest rates helped cause a boom in housing, which in turn led the U.S. economy out of recession. As housing boomed, however, financial institutions began taking on growing risks—

Subprime lending is lending to home-

Traditionally, people were only able to borrow money to buy homes if they could show that they had sufficient income to meet the mortgage payments. Home loans to people who don’t meet the usual criteria for borrowing, called subprime lending, were only a minor part of overall lending. But in the booming housing market of 2003–

In securitization, a pool of loans is assembled and shares of that pool are sold to investors.

Who was making these subprime loans? For the most part, it wasn’t traditional banks lending out depositors’ money. Instead, most of the loans were made by “loan originators,” who quickly sold mortgages to other investors. These sales were made possible by a process known as securitization: financial institutions assembled pools of loans and sold shares in the income from these pools. These shares were considered relatively safe investments, since it was considered unlikely that large numbers of home-

But that’s exactly what happened. The housing boom turned out to be a bubble, and when home prices started falling in late 2006, many subprime borrowers were unable either to meet their mortgage payments or sell their houses for enough to pay off their mortgages. As a result, investors in securities backed by subprime mortgages started taking heavy losses. Many of the mortgage-

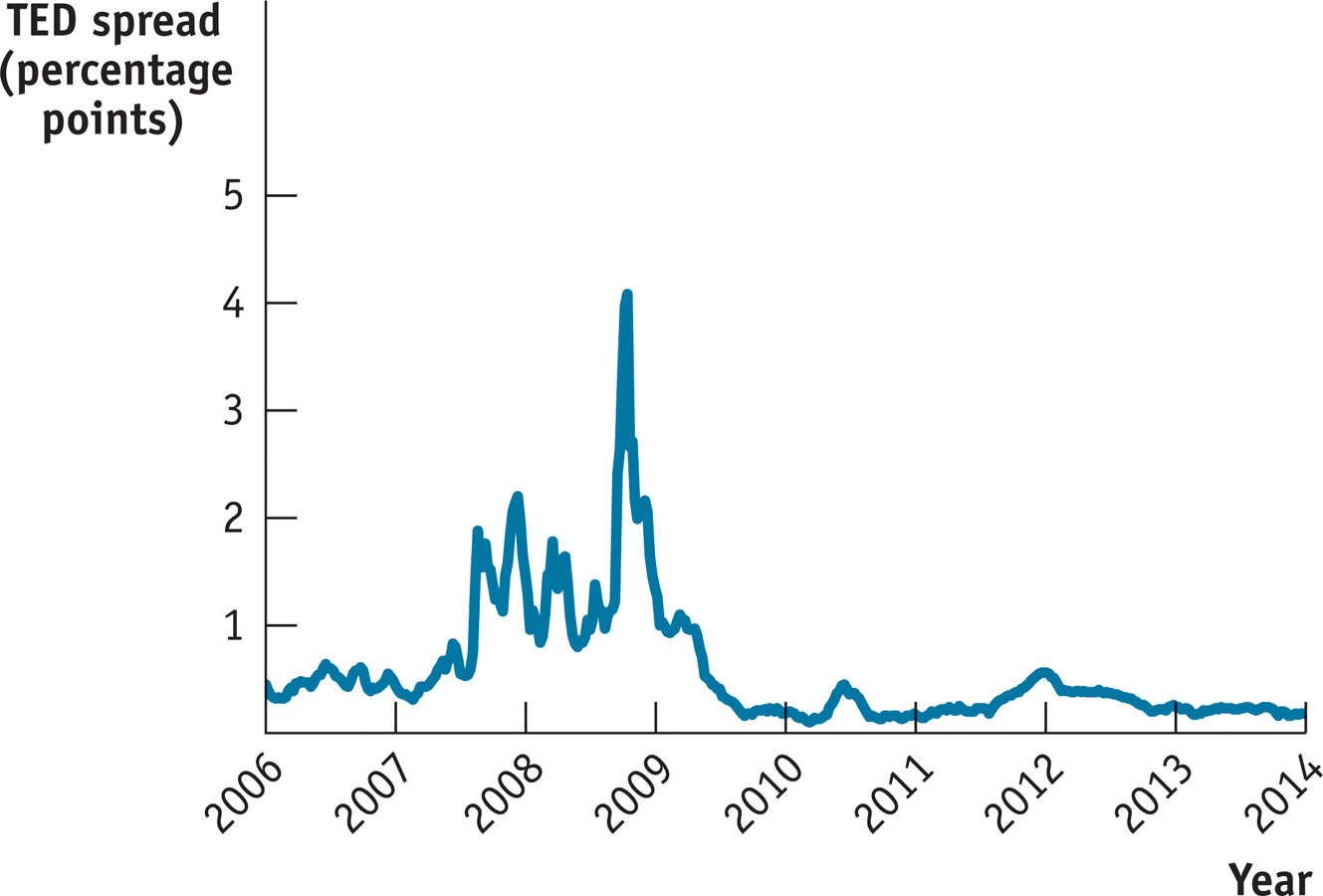

Figure 29-10 shows one measure of this loss of trust: the TED spread, which is the difference between the interest rate on three-

29-10

The TED Spread

Crisis and Response The collapse of trust in the financial system, combined with the large losses suffered by financial firms, led to a severe cycle of deleveraging and a credit crunch for the economy as a whole. Firms found it difficult to borrow, even for short-

Overall, the negative economic effect of the financial crisis bore a distinct and troubling resemblance to the effects of the banking crisis of the early 1930s, which helped cause the Great Depression. Policy makers noticed the resemblance and tried to prevent a repeat performance. Beginning in August 2007, the Federal Reserve engaged in a series of efforts to provide cash to the financial system, lending funds to a widening range of institutions and buying private-

In September 2008, however, policy makers decided that one major investment bank, Lehman Brothers, could be allowed to fail. They quickly regretted the decision. Within days of Lehman’s failure, widespread panic gripped the financial markets, as illustrated by the surge in the TED spread shown in Figure 29-10. In response to the intensified crisis, the U.S. government intervened further to support the financial system, as the U.S. Treasury began “injecting” capital into banks. Injecting capital, in practice, meant that the U.S. government would supply cash to banks in return for shares—

By the fall of 2010, the financial system appeared to be stabilized, and major institutions had repaid much of the money the federal government had injected during the crisis. It was generally expected that taxpayers would end up losing little if any money. However, the recovery of the banks was not matched by a successful turnaround for the overall economy: although the recession that began in December 2007 officially ended in June 2009, unemployment remained stubbornly high.

The Federal Reserve responded to this troubled situation with novel forms of open-

Like earlier crises, the crisis of 2008 led to changes in banking regulation, most notably the Dodd-

!worldview! ECONOMICS in Action: Regulation After the 2008 Crisis

Regulation After the 2008 Crisis

In July 2010, President Obama signed the Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act—

For the most part, it left regulation of traditional deposit-

The major changes came in the regulation of financial institutions other than banks—

These systemically important institutions would be subjected to bank-

Beyond this, the law established new rules on the trading of derivatives, those complex financial instruments that sank LTCM and played an important role in the 2008 crisis as well: most derivatives would henceforth have to be bought and sold on exchanges, where everyone could observe their prices and the volume of transactions. The idea was to make the risks taken by financial institutions more transparent.

Overall, Dodd-

Quick Review

The Federal Reserve system was created in response to the Panic of 1907.

Widespread bank runs in the early 1930s resulted in greater bank regulation and the creation of federal deposit insurance. Banks were separated into two categories: commercial (covered by deposit insurance) and investment (not covered).

In the savings and loan (thrift) crisis of the 1970s and 1980s, insufficiently regulated S&Ls incurred huge losses from risky speculation.

During the mid-

1990s, the hedge fund LTCM used huge amounts of leverage to speculate in global markets, incurred massive losses, and collapsed. In selling assets to cover its losses, LTCM caused balance sheet effects for firms around the world. To prevent a vicious cycle of deleveraging, the New York Fed coordinated a private bailout. In the mid-

2000s, loans from subprime lending spread through the financial system via securitization, leading to a financial crisis. The Fed responded by injecting cash into financial institutions and buying private debt. In 2010, the Dodd-

Frank bill revised financial regulation in an attempt to prevent repeats of the 2008 crisis.

29-5

Question 14.9

What are the similarities between the Panic of 1907, the S&L crisis, and the crisis of 2008?

The Panic of 1907, the S&L crisis, and the crisis of 2008 all involved losses by financial institutions that were less regulated than banks. In the crises of 1907 and 2008, there was a widespread loss of confidence in the financial sector and collapse of credit markets. Like the crisis of 1907 and the S&L crisis, the crisis of 2008 exerted a powerful negative effect on the economy.

Question 14.10

Why did the creation of the Federal Reserve fail to prevent the bank runs of the Great Depression? What measures stopped the bank runs?

The creation of the Federal Reserve failed to prevent bank runs because it did not eradicate the fears of depositors that a bank collapse would cause them to lose their money. The bank runs eventually stopped after federal deposit insurance was instituted and the public came to understand that their deposits were now protected.

Question 14.11

Describe the balance sheet effect. Describe the vicious cycle of deleveraging. Why is it necessary for the government to step in to halt a vicious cycle of deleveraging?

The balance sheet effect occurs when asset sales cause declines in asset prices, which then reduce the value of other firms’ net worth as the value of the assets on their balance sheets declines. In the vicious cycle of deleveraging, the balance sheet effect on firms forces their creditors to call in their loan contracts, forcing the firms to sell assets to pay back their loans, leading to further asset sales and price declines. Because the vicious cycle of deleveraging occurs across different firms and no single firm can stop it, it is necessary for the government to step in to stop it.

Solutions appear at back of book.

The Perfect Gift: Cash or a Gift Card?

It’s always nice when someone shows his or her appreciation by giving you a gift. Over the past few years, more and more people have been showing their appreciation by giving gift cards, prepaid plastic cards issued by a retailer that can be redeemed for merchandise. The best-

What could be more simple and useful than allowing the recipient to choose what he or she wants? And isn’t a gift card more personal than cash or a check?

Yet several websites are now making a profit from the fact that gift card recipients are often willing to sell their cards at a discount—

Cardpool.com is one such site. At the time of writing, it offers to pay cash to a seller of a Whole Foods gift card equivalent to 88% of the card’s face value. For example, the seller of a card with a value of $100 would receive $88 in cash. But it offers cash equal to only 70% of a Gap card’s face value. Cardpool.com profits by reselling the card at a premium over what it paid; for example, it buys a Whole Foods card for 88% of its face value and then resells it for 97% of its face value.

Many consumers will sell at a sizable discount to turn gift cards into cash. But retailers promote the use of gift cards over cash because much of the value of gift cards issued never gets used, a phenomenon known as breakage.

How does breakage occur? People lose cards. Or they spend only $47 of a $50 gift card, and never return to the store to spend that last $3. Also, retailers impose fees on the use of cards or make them subject to expiration dates, which customers forget about. And if a retailer goes out of business, the value of outstanding gift cards disappears with it.

In addition to breakage, retailers benefit when customers intent on using up the value of their gift card find that it is too difficult to spend exactly the amount of the card. Instead, they end up spending more than the card’s face value, sometimes even more than they would have without the gift card.

Gift cards are so beneficial to retailers that instead of rewarding customer loyalty with rebate checks (once a common practice), they have switched to dispensing gift cards. As one commentator noted in explaining why retailers prefer gift cards to rebate checks, “Nobody neglects to spend cash.”

However, the future may not be quite so profitable for gift card issuers. Hard economic times have made consumers more careful about spending down their cards. And legislation enacted in 2009 requires that cards remain valid for at least five years. As a result, breakage has fallen sharply, although it still amounts to more than $1 billion a year.

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

Question 14.12

Why are gift card owners willing to sell their cards for a cash amount less than their face value?

Why are gift card owners willing to sell their cards for a cash amount less than their face value?Question 14.13

Why do gift cards for retailers like Walmart, Home Depot, and Whole Foods sell for a smaller discount than those for retailers like the Gap and Aeropostale?

Why do gift cards for retailers like Walmart, Home Depot, and Whole Foods sell for a smaller discount than those for retailers like the Gap and Aeropostale?Question 14.14

Use your answer from Question 2 to explain why cash never “sells” at a discount.

Use your answer from Question 2 to explain why cash never “sells” at a discount.Question 14.15

Explain why retailers prefer to reward loyal customers with gift cards instead of rebate checks.

Explain why retailers prefer to reward loyal customers with gift cards instead of rebate checks.Question 14.16

Recent legislation restricted retailers’ ability to impose fees and expiration dates on their gift cards and mandated greater disclosure of their terms. Why do you think Congress enacted this legislation?

Recent legislation restricted retailers’ ability to impose fees and expiration dates on their gift cards and mandated greater disclosure of their terms. Why do you think Congress enacted this legislation?