10.4 Public Goods

The opening story described the Great Stink of 1858, a negative externality created by individuals dumping waste into the Thames.

What the city needed, said reformers at the time, was a sewage system that would carry waste away from the river. Yet no private individual was willing to build such a system, and influential people were opposed to the idea that the government should take responsibility for the problem.

302

As we saw in the story, Parliament approved a plan for an immense system of sewers and pumping stations with the result that cholera and typhoid epidemics, which had been regular occurrences, completely disappeared. The Thames was turned from the filthiest to the cleanest metropolitan river in the world, and the sewage system’s principal engineer, Sir Joseph Bazalgette, was lauded as having “saved more lives than any single Victorian public official.” It was estimated at the time that Bazalgette’s sewer system added 20 years to the life span of the average Londoner.

So, what’s the difference between installing a new bathroom in a house and building a municipal sewage system? What’s the difference between growing wheat and fishing in the open ocean?

These aren’t trick questions. In each case there is a basic difference in the characteristics of the goods involved. Bathroom fixtures and wheat have the characteristics necessary to allow markets to work efficiently. Public sewage systems and fish in the sea do not.

Let’s look at these crucial characteristics and why they matter.

Characteristics of Goods

Goods like bathroom fixtures or wheat have two characteristics that, as we’ll soon see, are essential if a good is to be efficiently provided by a market economy.

A good is excludable if the supplier of that good can prevent people who do not pay from consuming it.

A good is rival in consumption if the same unit of the good cannot be consumed by more than one person at the same time.

They are excludable: suppliers of the good can prevent people who don’t pay from consuming it.

They are rival in consumption: the same unit of the good cannot be consumed by more than one person at the same time.

A good that is both excludable and rival in consumption is a private good.

When a good is both excludable and rival in consumption, it is called a private good. Wheat is an example of a private good. It is excludable: the farmer can sell a bushel to one consumer without having to provide wheat to everyone in the county. And it is rival in consumption: if I eat bread baked with a farmer’s wheat, that wheat cannot be consumed by someone else.

When a good is nonexcludable, the supplier cannot prevent consumption by people who do not pay for it.

But not all goods possess these two characteristics. Some goods are nonexcludable—

A good is nonrival in consumption if more than one person can consume the same unit of the good at the same time.

Nor are all goods rival in consumption. Goods are nonrival in consumption if more than one person can consume the same unit of the good at the same time. TV programs are nonrival in consumption: your decision to watch a show does not prevent other people from watching the same show.

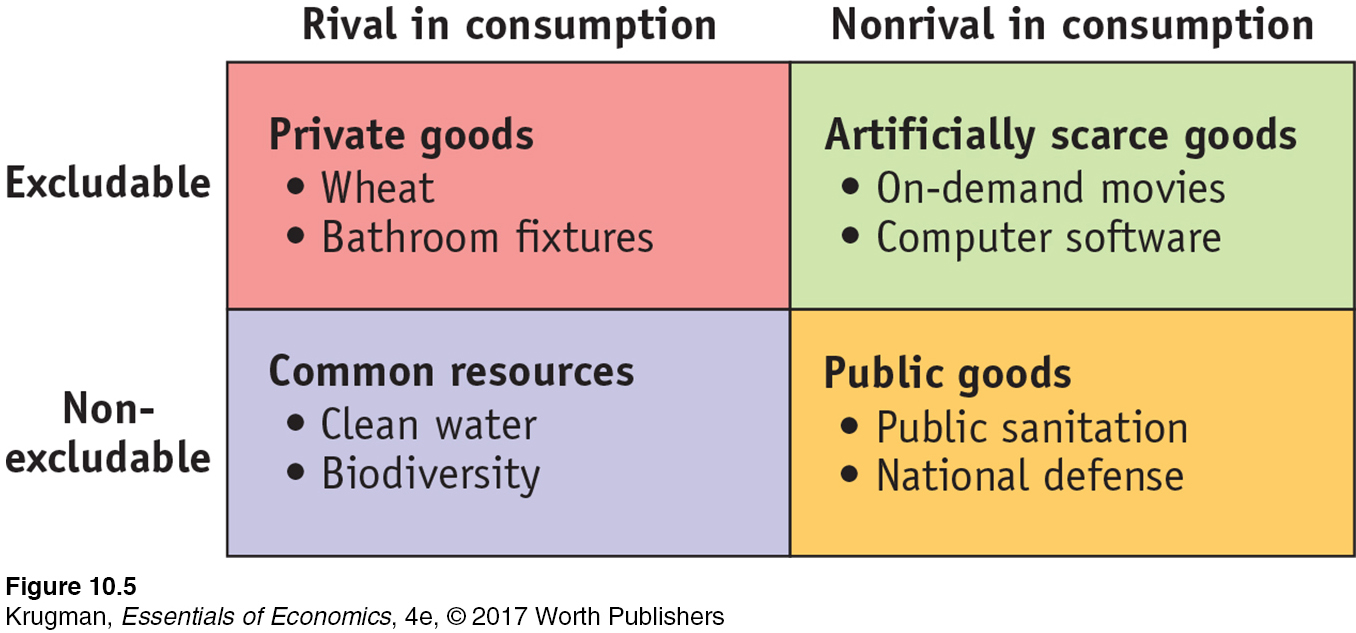

Because goods can be either excludable or nonexcludable, rival or nonrival in consumption, there are four types of goods, illustrated by Figure 10-5.

Private goods, which are excludable and rival in consumption, like wheat

Public goods, which are nonexcludable and nonrival in consumption, like a public sewer system

Common resources, which are nonexcludable but rival in consumption, like clean water in a river

Artificially scarce goods, which are excludable but nonrival in consumption, like on-

demand movies on DirecTV

303

There are, of course, many other characteristics that distinguish between types of goods—

Why Markets Can Supply Only Private Goods Efficiently

As we’ve learned markets are typically the best means for a society to deliver goods and services to its members; that is, markets are efficient except in the case of the well-

To see why excludability is crucial, suppose that a farmer had only two choices: either produce no wheat or provide a bushel of wheat to every resident of the county who wants it, whether or not that resident pays for it. It seems unlikely that anyone would grow wheat under those conditions.

Yet the operator of a municipal sewage system faces pretty much the same problem as our hypothetical farmer. A sewage system makes the whole city cleaner and healthier—

Goods that are nonexcludable suffer from the free-

The general point is that if a good is nonexcludable, self-

PITFALLS

MARGINAL COST OF WHAT EXACTLY?

In the case of a good that is nonrival in consumption, it’s easy to confuse the marginal cost of producing a unit of the good with the marginal cost of allowing a unit of the good to be consumed. For example, DirecTV incurs a marginal cost in making a movie available to its subscribers that is equal to the cost of the resources it uses to produce and broadcast that movie. However, once that movie is being broadcast, no marginal cost is incurred by letting an additional family watch it. In other words, no costly resources are “used up” when one more family consumes a movie that has already been produced and is being broadcast.

This complication does not arise, however, when a good is rival in consumption. In that case, the resources used to produce a unit of the good are “used up” by a person’s consumption of it—

Because of the free-

Goods that are excludable and nonrival in consumption, like on-

But if DirecTV actually charges viewers $4, viewers will consume the good only up to the point where their marginal benefit is $4. When consumers must pay a price greater than zero for a good that is nonrival in consumption, the price they pay is higher than the marginal cost of allowing them to consume that good, which is zero. So in a market economy goods that are nonrival in consumption suffer from inefficiently low consumption.

Now we can see why private goods are the only goods that can be efficiently produced and consumed in a competitive market. (That is, a private good will be efficiently produced and consumed in a market free of market power, externalities, or other instances of market failure.) Because private goods are excludable, producers can charge for them and so have an incentive to produce them. And because they are also rival in consumption, it is efficient for consumers to pay a positive price—

304

Fortunately for the market system, most goods are private goods. Food, clothing, shelter, and most other desirable things in life are excludable and rival in consumption, so markets can provide us with most things. Yet there are crucial goods that don’t meet these criteria—

Providing Public Goods

A public good is both nonexcludable and nonrival in consumption.

A public good is the exact opposite of a private good: it is a good that is both nonexcludable and nonrival in consumption. A public sewer system is an example of a public good: you can’t keep a river clean without making it clean for everyone who lives near its banks, and my protection from great stinks does not come at my neighbor’s expense.

Here are some other examples of public goods:

Disease prevention. When doctors act to stamp out the beginnings of an epidemic before it can spread, they protect people around the world.

National defense. A strong military protects all citizens.

Scientific research. More knowledge benefits everyone.

Because these goods are nonexcludable, they suffer from the free-

Public goods are provided through a variety of means. The government doesn’t always get involved—

Some public goods are supplied through voluntary contributions. For example, private donations support a considerable amount of scientific research. But private donations are insufficient to finance huge, socially important projects like basic medical research.

Some public goods are supplied by self-

Some potentially public goods are deliberately made excludable and therefore subject to charge, like on-

305

In small communities, a high level of social encouragement or pressure can be brought to bear on people to contribute money or time to provide the efficient level of a public good. Volunteer fire departments, which depend both on the volunteered services of the firefighters themselves and on contributions from local residents, are a good example. But as communities grow larger and more anonymous, social pressure is increasingly difficult to apply, compelling larger towns and cities to tax residents to provide salaried firefighters for fire protection services.

As this last example suggests, when these other solutions fail, it is up to the government to provide public goods. Indeed, the most important public goods—

How Much of a Public Good Should Be Provided?

In some cases, provision of a public good is an “either–or” decision: London would either have a sewage system—

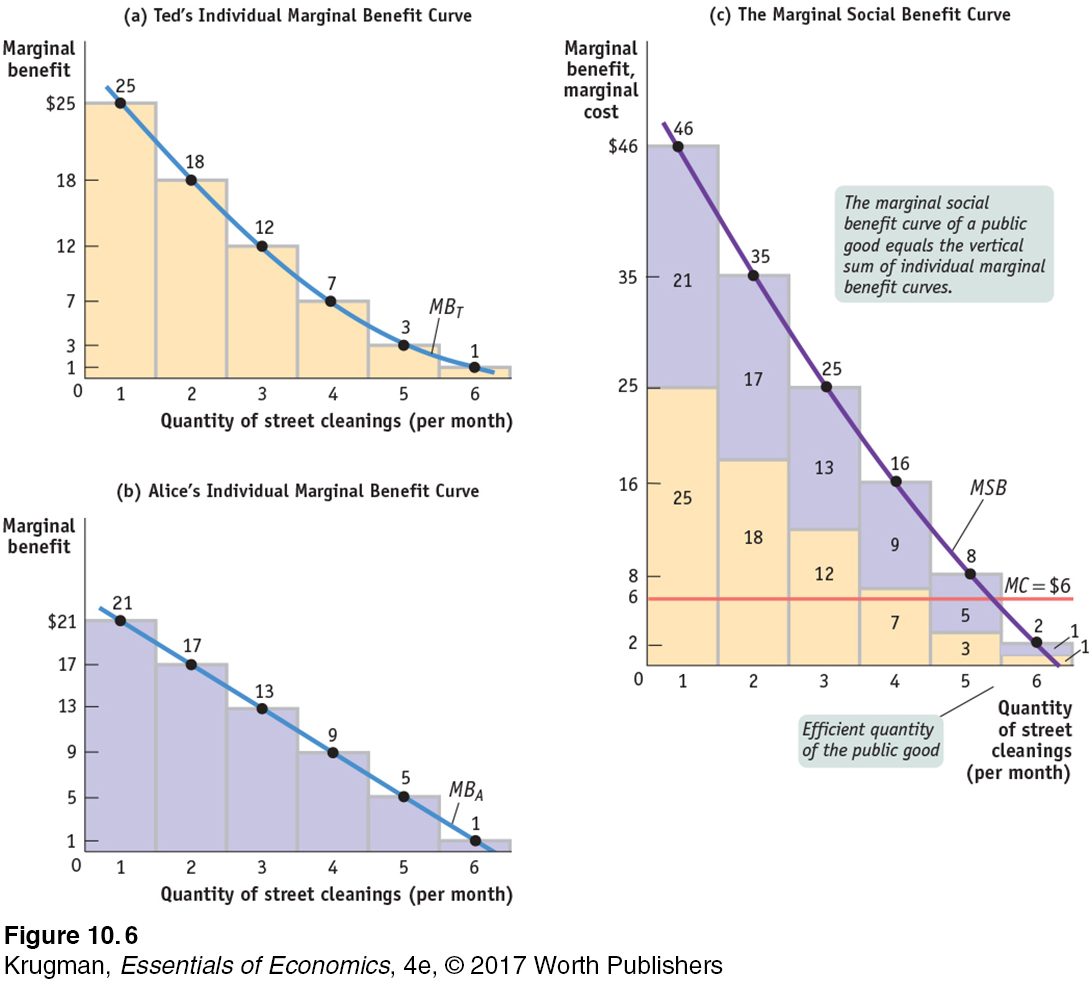

Imagine a city in which there are only two residents, Ted and Alice. Assume that the public good in question is street cleaning and that Ted and Alice truthfully tell the government how much they value a unit of the public good, where a unit is equal to one street cleaning per month. Specifically, each of them tells the government his or her willingness to pay for another unit of the public good supplied—an amount that corresponds to that individual’s marginal benefit of another unit of the public good.

Using this information plus information on the cost of providing the good, the government can use marginal analysis to find the efficient level of providing the public good: the level at which the marginal social benefit of the public good is equal to the marginal cost of producing it. Earlier we explained that the marginal social benefit of a good is the benefit that accrues to society as a whole from the consumption of one additional unit of the good.

But what is the marginal social benefit of another unit of a public good—

Why? Because a public good is nonrival in consumption—

306

Figure 10-6 illustrates the efficient provision of a public good, showing three marginal benefit curves. Panel (a) shows Ted’s individual marginal benefit curve from street cleaning, MBT: he would be willing to pay $25 for the city to clean its streets once a month, an additional $18 to have it done a second time, and so on. Panel (b) shows Alice’s individual marginal benefit curve from street cleaning, MBA. Panel (c) shows the marginal social benefit curve from street cleaning, MSB: it is the vertical sum of Ted’s and Alice’s individual marginal benefit curves, MBT and MBA.

To maximize society’s welfare, the government should clean the street up to the level at which the marginal social benefit of an additional cleaning is no longer greater than the marginal cost. Suppose that the marginal cost of street cleaning is $6 per cleaning. Then the city should clean its streets 5 times per month, because the marginal social benefit of going from 4 to 5 cleanings is $8, but going from 5 to 6 cleanings would yield a marginal social benefit of only $2.

307

Figure 10-6 can help reinforce our understanding of why we cannot rely on individual self-

The point is that the marginal social benefit of one more unit of a public good is always greater than the individual marginal benefit to any one individual. That is why no individual is willing to pay for the efficient quantity of the good.

Does this description of the public-

In the case of a public good, the individual marginal benefit of a consumer plays the same role as the price received by the producer in the case of positive externalities: both cases create insufficient incentive to provide an efficient amount of the good.

The problem of providing public goods is very similar to the problem of dealing with positive externalities; in both cases there is a market failure that calls for government intervention. One basic rationale for the existence of government is that it provides a way for citizens to tax themselves in order to provide public goods—

Of course, if society really consisted of only two individuals, they would probably manage to strike a deal to provide the good. But imagine a city with a million residents, each of whose individual marginal benefit from provision of the good is only a tiny fraction of the marginal social benefit. It would be impossible for people to reach a voluntary agreement to pay for the efficient level of street cleaning—

Cost-

Cost-

How do governments decide in practice how much of a public good to provide? Sometimes policy makers just guess—

It’s straightforward to estimate the cost of supplying a public good. Estimating the benefit is harder. In fact, it is a very difficult problem.

You might wonder why governments can’t figure out the marginal social benefit of a public good just by asking people their willingness to pay for it (their individual marginal benefit). But it turns out that it’s hard to get an honest answer.

This is not a problem with private goods: we can determine how much an individual is willing to pay for one more unit of a private good by looking at his or her actual choices. But because people don’t actually pay for public goods, the question of willingness to pay is always hypothetical.

308

Worse yet, it’s a question that people have an incentive not to answer truthfully. People naturally want more rather than less. Because they cannot be made to pay for whatever quantity of the public good they use, people are apt to overstate their true feelings when asked how much they desire a public good. For example, if street cleaning were scheduled according to the stated wishes of homeowners alone, the streets would be cleaned every day—

So governments must be aware that they cannot simply rely on the public’s statements when deciding how much of a public good to provide—

ECONOMICS in Action

Old Man River

| interactive activity

| interactive activity

It just keeps rolling along—

So when is the Mississippi due to change course again? Oh, about 45 years ago.

The Mississippi currently runs to the sea past New Orleans; but by 1950 it was apparent that the river was about to shift course, taking a new route to the sea. If the Army Corps of Engineers hadn’t gotten involved, the shift would probably have happened by 1970.

A shift in the Mississippi would have severely damaged the Louisiana economy. A major industrial area would have lost good access to the ocean, and salt water would have contaminated much of its water supply. So the Army Corps of Engineers has kept the Mississippi in its place with a huge complex of dams, walls, and gates known as the Old River Control Structure. At times the amount of water released by this control structure is five times the flow at Niagara Falls.

The Old River Control Structure is a dramatic example of a public good. No individual would have had an incentive to build it, yet it protects many billions of dollars’ worth of private property. The history of the Army Corps of Engineers, which handles water-

The flip-

Although it was well understood from the time of its founding that New Orleans was at risk for severe flooding because it sits below sea level, very little was done to shore up the crucial system of levees and pumps that protects the city. More than 50 years of inadequate funding for construction and maintenance, coupled with inadequate supervision, left the system weakened and unable to cope with the onslaught from Katrina. The catastrophe was compounded by the failure of local and state government to develop an evacuation plan in the event of a hurricane. In the end, because of this neglect of a public good, 1,464 people in and around New Orleans lost their lives and the city suffered economic losses totaling billions of dollars.

309

Quick Review

Goods can be classified according to two attributes: whether they are excludable and whether they are rival in consumption.

Goods that are both excludable and rival in consumption are private goods. Private goods can be efficiently produced and consumed in a competitive market.

When goods are nonexcludable, there is a free-

rider problem: consumers will not pay producers, leading to inefficiently low production. When goods are nonrival in consumption, the efficient price for consumption is zero.

A public good is both nonexcludable and nonrival in consumption.

Although governments should rely on cost-

benefit analysis to determine how much of a public good to supply, doing so is problematic because individuals tend to overstate the good’s value to them.

Check Your Understanding 10-

Question 10.7

1. Classify each of the following goods according to whether they are excludable and whether they are rival in consumption. What kind of good is each?

Use of a public space such as a park

Use of a public park is nonexcludable, but it may or may not be rival in consumption, depending on the circumstances. For example, if both you and I use the park for jogging, then your use will not prevent my use—

use of the park is nonrival in consumption. In this case the public park is a public good. But use of the park is rival in consumption if there are many people trying to use the jogging path at the same time or when my use of the public tennis court prevents your use of the same court. In this case the public park is a common resource. A cheese burrito

A cheese burrito is both excludable and rival in consumption. Hence it is a private good.

Information from a website that is password-

protected Information from a password-

protected website is excludable but nonrival in consumption. So it is an artificially scarce good. Publicly announced information on the path of an incoming hurricane

Publicly announced information on the path of an incoming hurricane is nonexcludable and nonrival in consumption. So it is a public good.

Question 10.8

2. The town of Centreville, population 16, has two types of residents, Homebodies and Revelers. Using the accompanying table, the town must decide how much to spend on its New Year’s Eve party. No individual resident expects to directly bear the cost of the party.

| Money spent on party |

Individual marginal benefit of additional $1 spent on party |

|

| Homebody | Reveler | |

| $0 | ||

| $0.05 | $0.13 | |

| 1 | ||

| 0.04 | 0.11 | |

| 2 | ||

| 0.03 | 0.09 | |

| 3 | ||

| 0.02 | 0.07 | |

| 4 | ||

Suppose there are 10 Homebodies and 6 Revelers. Determine the marginal social benefit schedule of money spent on the party. What is the efficient level of spending?

With 10 Homebodies and 6 Revelers, the marginal social benefit schedule of money spent on the party is as shown in the accompanying table.

Money spent

on partyMarginal social benefit $0 (10 × $0.05) + (6 × $0.13) = $1.28 1 (10 × $0.04) + (6 × $0.11) = $1.06 2 (10 × $0.03) + (6 × $0.09) = $0.84 3 (10 × $0.02) + (6 × $0.07) = $0.62 4 The efficient spending level is $2, the highest level for which the marginal social benefit is greater than the marginal cost ($1).

Suppose there are 6 Homebodies and 10 Revelers. How do your answers to part a change? Explain.

With 6 Homebodies and 10 Revelers, the marginal social benefit schedule of money spent on the party is as shown in the accompanying table.

Money spent

on partyMarginal social benefit $0 (6 × $0.05) + (10 × $0.13) = $1.60 1 (6 × $0.04) + (10 × $0.11) = $1.34 2 (6 × $0.03) + (10 × $0.09) = $1.08 3 (6 × $0.02) + (10 × $0.07) = $0.82 4 The efficient spending level is now $3, the highest level for which the marginal social benefit is greater than the marginal cost ($1). The efficient level of spending has increased from that in part a because with relatively more Revelers than Homebodies, an additional dollar spent on the party generates a higher level of social benefit compared to when there are relatively more Homebodies than Revelers.

Suppose that the individual marginal benefit schedules are known but no one knows the true proportion of Homebodies versus Revelers. Individuals are asked their preferences. What is the likely outcome if each person assumes that others will pay for any additional amount of the public good? Why is it likely to result in an inefficiently high level of spending? Explain.

When the numbers of Homebodies and Revelers are unknown but residents are asked their preferences, Homebodies will pretend to be Revelers to induce a higher level of spending on the public party. That’s because a Homebody still receives a positive individual marginal benefit from an additional $1 spent, despite the fact that his or her individual marginal benefit is lower than that of a Reveler for every additional $1. In this case the “reported” marginal social benefit schedule of money spent on the party will be as shown in the accompanying table.

Money spent

on partyMarginal social benefit $0 16 × $0.13 = $2.08 1 16 × $0.11 = $1.76 2 16 × $0.09 = $1.44 3 16 × $0.07 = $1.12 4 As a result, $4 will be spent on the party, the highest level for which the “reported” marginal social benefit is greater than the marginal cost ($1). Regardless of whether there are 10 Homebodies and 6 Revelers (part a) or 6 Homebodies and 10 Revelers (part b), spending $4 in total on the party is clearly inefficient because marginal cost exceeds marginal social benefit at this spending level.

As a further exercise, consider how much Homebodies gain by this misrepresentation. In part a, the efficient level of spending is $2. So by misrepresenting their preferences, the 10 Homebodies gain, in total, 10 × ($0.03 + $0.02) = $0.50—

that is, they gain the marginal individual benefit in going from a spending level of $2 to $4. The 6 Revelers also gain from the misrepresentations of the Homebodies; they gain 6 × ($0.09 + $0.07) = $0.96 in total. This outcome is clearly inefficient— when $4 in total is spent, the marginal cost is $1 but the marginal social benefit is only $0.62, indicating that too much money is being spent on the party. In part b, the efficient level of spending is actually $3. The misrepresentation by the 6 Homebodies gains them, in total, 6 × $0.02 = $0.12, but the 10 Revelers gain 10 × $0.07 = $0.70 in total. This outcome is also clearly inefficient—

when $4 is spent, marginal social benefit is only $0.12 + $0.70 = $0.82 but marginal cost is $1.

Solutions appear at back of book.