11.3 The Economics of Health Care

A large part of the welfare state, in both the United States and other wealthy countries, is devoted to paying for health care. In most wealthy countries, the government pays between 70% and 90% of all medical costs. The private sector plays a larger role in the U.S. health care system. Yet even in America, as of 2014 the government pays almost half of all health care costs; furthermore, it indirectly subsidizes private health insurance through the federal tax code.

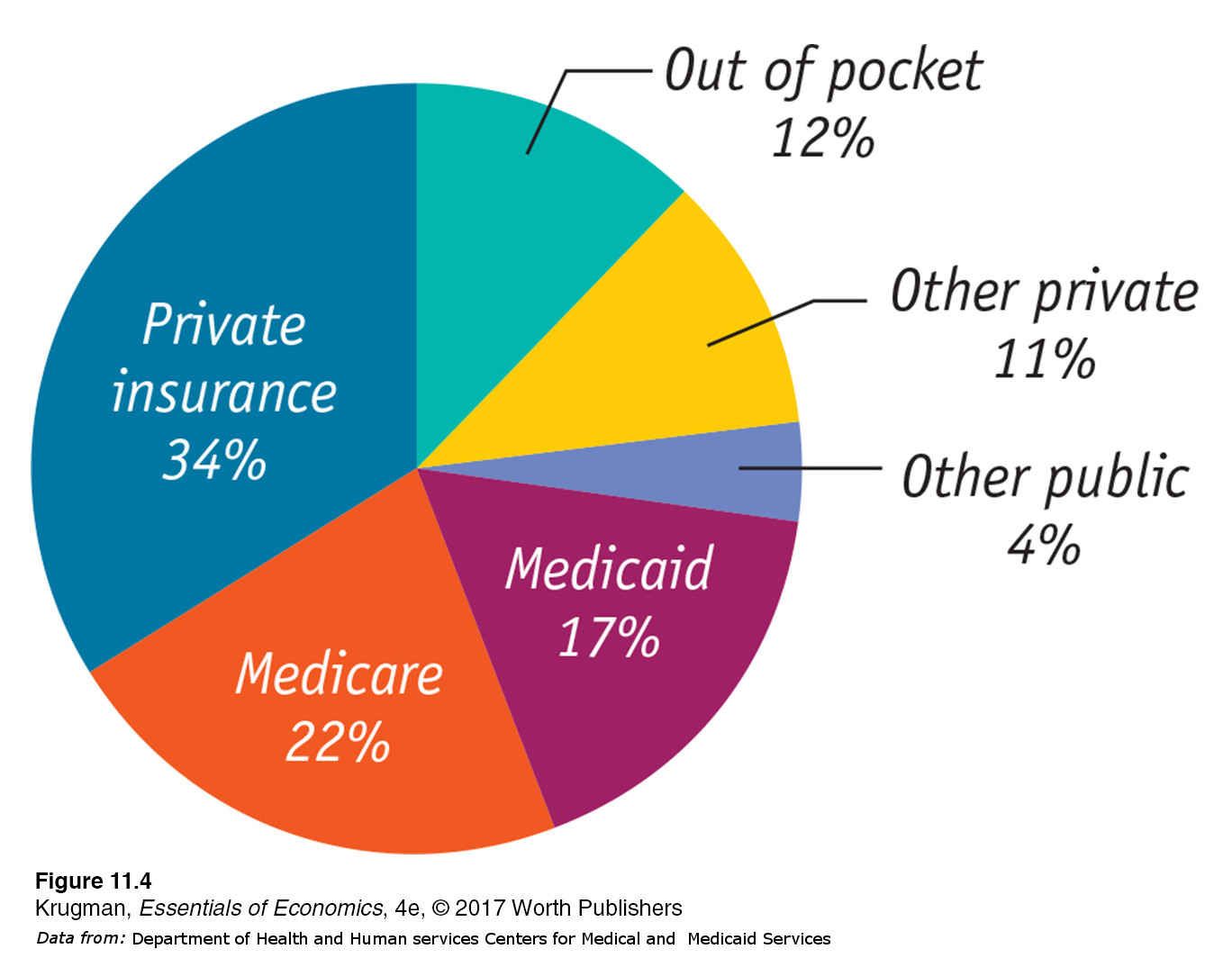

Figure 11-4 shows who paid for U.S. health care in 2014. Only 12% of health care consumption spending (that is, all spending on health care except investment in health care buildings and facilities) was expenses “out of pocket”—that is, paid directly by individuals. Most health care spending, 77%, was paid for by some kind of insurance. Of this 77%, considerably less than half was private insurance; the rest was some kind of government insurance, mainly Medicare and Medicaid. To understand why, we need to examine the special economics of health care.

The Need for Health Insurance

In 2014, U.S. personal health care expenses were $9,523 per person—

Is it possible to predict who will have high medical costs? To a limited extent, yes: there are broad patterns to illness. For example, the elderly are more likely to need expensive surgery and/or drugs than the young. But the fact is that anyone can suddenly find himself or herself needing very expensive medical treatment, costing many thousands of dollars in a very short time—

Under private health insurance, each member of a large pool of individuals pays a fixed amount annually to a private company that agrees to pay most of the medical expenses of the pool’s members.

Private Health Insurance Market economies have an answer to this problem: health insurance. Under private health insurance, each member of a large pool of individuals agrees to pay a fixed amount annually (called a premium) into a common fund that is managed by a private company, which then pays most of the medical expenses of the pool’s members. Although members must pay fees even in years in which they don’t have large medical expenses, they benefit from the reduction in risk: if they do turn out to have high medical costs, the pool will take care of those expenses.

There are, however, inherent problems with the market for private health insurance that arise from the fact that medical expenses, although basically unpredictable, aren’t completely unpredictable. People often have some idea whether or not they are likely to face large medical bills over the next few years. This creates a serious problem for private health insurance companies.

Suppose that an insurance company offers a “one-

If all potential customers had an equal risk of incurring high medical expenses for the year, this might be a workable business proposition. In reality, however, people often have different risks of facing high medical expenses—

As a result, some healthy people are likely to take their chances and go without insurance. This would make the insurance company’s average customer less healthy than the average American, raising both the medical bills the company will have to pay and its costs per customer.

The insurance company could respond by charging more—

This description of the problems with health insurance might lead you to believe that private health insurance can’t work. In fact, however, most Americans are covered by private health insurance. Insurance companies are able, to some extent, to overcome the problems we just outlined in two ways: by carefully screening applicants and through employment-

With screening, people who are likely to have high medical expenses are charged higher-

Employment-

There’s another reason employment-

However, many working Americans don’t receive employment-

Government Health Insurance

Table 11-5 shows the breakdown of health insurance coverage across the U.S. population in 2014. A majority of Americans, nearly 175 million people, received health insurance through their employers. The majority of those who didn’t have private insurance were covered by two government programs, Medicare and Medicaid. (The numbers don’t add up because some people have more than one form of coverage. For example, many recipients of Medicare also have supplemental coverage through Medicaid or private policies.)

| Covered by private health insurance | 208.6 |

| Employment- |

175.0 |

| Direct purchase | 46.2 |

| Covered by government | 115.5 |

| Medicaid | 50.5 |

| Medicare | 61.7 |

| Military health care | 14.1 |

| Not covered | 33.0 |

|

Data from: U.S. Census Bureau. |

|

Medicare, like Social Security, is financed by payroll taxes, and is available to all Americans 65 and older, regardless of their income and wealth. It began in 1966 as a program to cover the cost of hospitalization but has since been expanded to cover a number of other medical expenses. You can get an idea of how much difference Medicare makes to the finances of elderly Americans by comparing the median income per person of Americans 65 and older—

Unlike Medicare, Medicaid is a means-

Nearly 14 million Americans receive health insurance as a consequence of military service. Unlike Medicare and Medicaid, which pay medical bills but don’t deliver health care directly, the Veterans Health Administration, which has more than 8 million clients, runs hospitals and clinics around the country.

The U.S. health care system, then, offers a mix of private insurance, mainly from employers, and public insurance of various forms. Most Americans have health insurance from either private insurance companies or through various forms of government insurance.

Health Care in Other Countries

Health care is one area in which the United States is very different from other wealthy countries, including European nations and Canada. In fact, we’re distinctive in three ways.

We rely much more on private health insurance.

We spend much more on health care per person.

We were the only wealthy nation in which large numbers of people lacked health insurance until the ACA started to change that.

Table 11-6 compares the United States with three other wealthy countries: Canada, France, and Britain. The United States is the only one of the four countries that relies on private health insurance to cover most people; as a result, it’s the only one in which private spending on health care is (slightly) larger than public spending on health care.

| Government share of health care spending |

Health care spending per capita (US$, purchasing power parity) |

Life expectancy (total population at birth, years) |

Infant mortality (deaths per 1,000 live births) |

|

| United States | 48.2% | $8,713 | 78.8 | 5.9 |

| Canada | 70.6 | 4,351 | 81.4 | 4.6 |

| France | 78.7 | 4,223 | 82.0 | 3.6 |

| Britain | 86.6 | 3,234 | 81.0 | 3.9 |

|

Data from: OECD; World Bank. |

||||

Canada has a single-

Canada, Britain, and France provide health insurance to all their citizens; the United States does not. Yet all three spend much less on health care per person than we do. Many Americans assume this must mean that foreign health care is inferior in quality. But many health care experts disagree, pointing out that Britain, Canada, and France generally match or exceed the United States in terms of many measures of health care provision, such as the number of doctors, nurses, and hospital beds per 100,000 people. Although it’s true that U.S. medical care includes more advanced technology in some areas, many more expensive surgical procedures, and shorter waiting times for elective surgery, surveys of patients seem to suggest that there are no significant differences in the quality of care in Canada, Europe, and the United States.

So why does the United States spend so much more on health care than other wealthy countries? Some of the disparity is the result of higher doctors’ salaries, but most studies suggest that this is a secondary factor. One possibility is that Americans are getting better care than their counterparts abroad, but in ways that don’t show up in either patient surveys or statistics on health performance.

The most likely explanation is that the U.S. system suffers from serious inefficiencies that other countries manage to avoid. Critics of the U.S. system emphasize the fact that our system’s reliance on private insurance companies makes it highly fragmented and very expensive to operate. Each insurance company expends resources on overhead and on such activities as marketing and trying to identify and weed out high-

Americans also pay higher prices for prescription drugs because, in other countries, government agencies bargain with pharmaceutical companies to get lower drug prices.

The Affordable Care Act

However one rates the past performance of the U.S. health care system, by 2009 it was clearly in trouble, on two fronts.

The percentage of uninsured working-

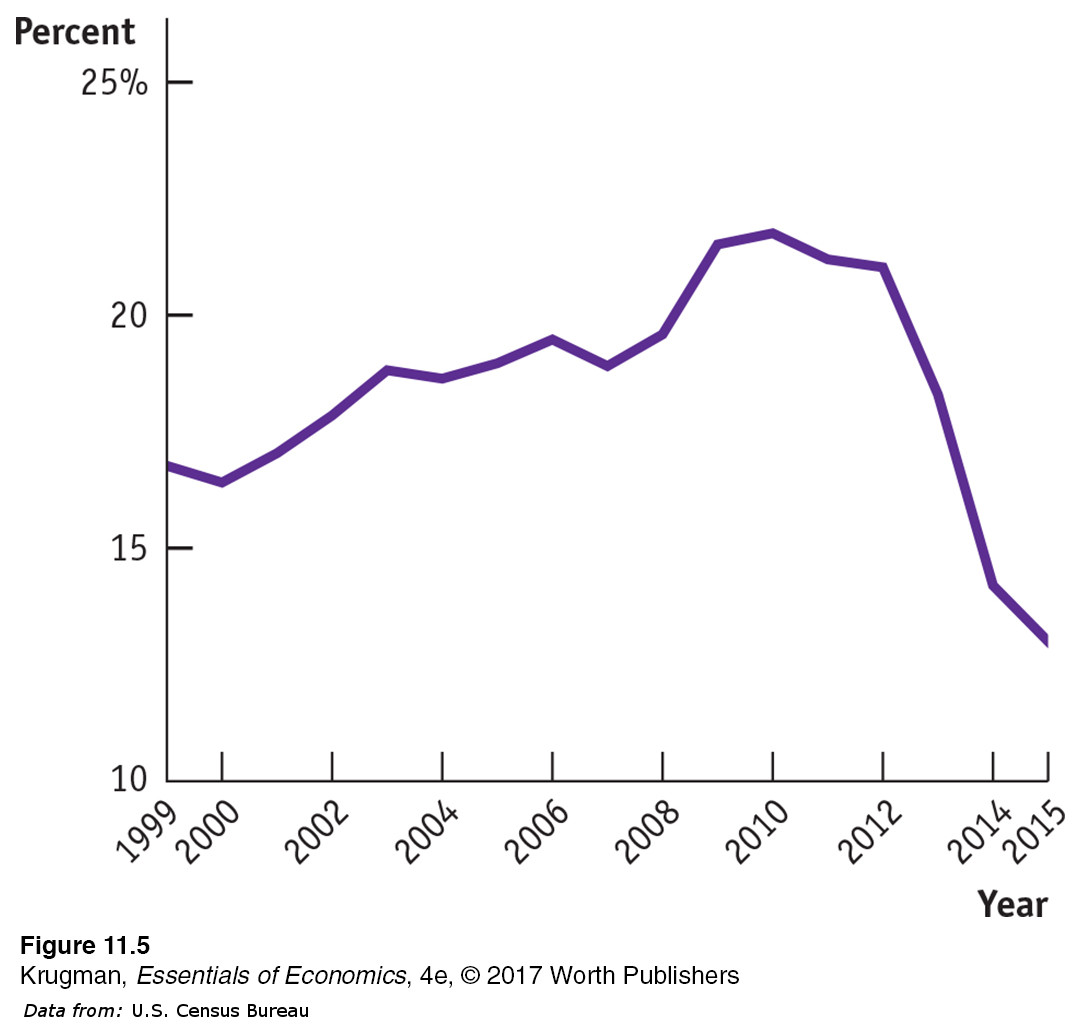

age Americans (considered to be those between the ages of 18 and 64) was on a clear upward trend, as shown in Figure 11-5. A study by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that: “The uninsured are largely low- income adult workers for whom coverage is unaffordable or unavailable.” They found that low- income workers tended to be uninsured because they were less likely than workers with higher incomes to have jobs that provide health insurance benefits, and were less likely to be able to afford to directly purchase health insurance themselves. Figure 11.5: FIGURE 11-5 Uninsured Working-Age Americans, 1999–2015  Figure 11.5: Older Americans are covered by Medicare, and many children also receive government-

Figure 11.5: Older Americans are covered by Medicare, and many children also receive government-provided insurance. The fraction of working- age adults without health insurance was, however, rising steadily before the Affordable Care Act went into effect. Data from: U.S. Census Bureau.Before the ACA, insurance companies often refused to cover people, regardless of their income, if they had a preexisting medical condition or if their medical history suggested they were likely to need expensive medical treatment in the future. As a result, a significant number of Americans with incomes that most would consider middle class could not get insurance. Like poverty, the lack of health insurance has severe medical and financial consequences: the uninsured frequently have limited access to health care and they often face serious financial problems when illness strikes.

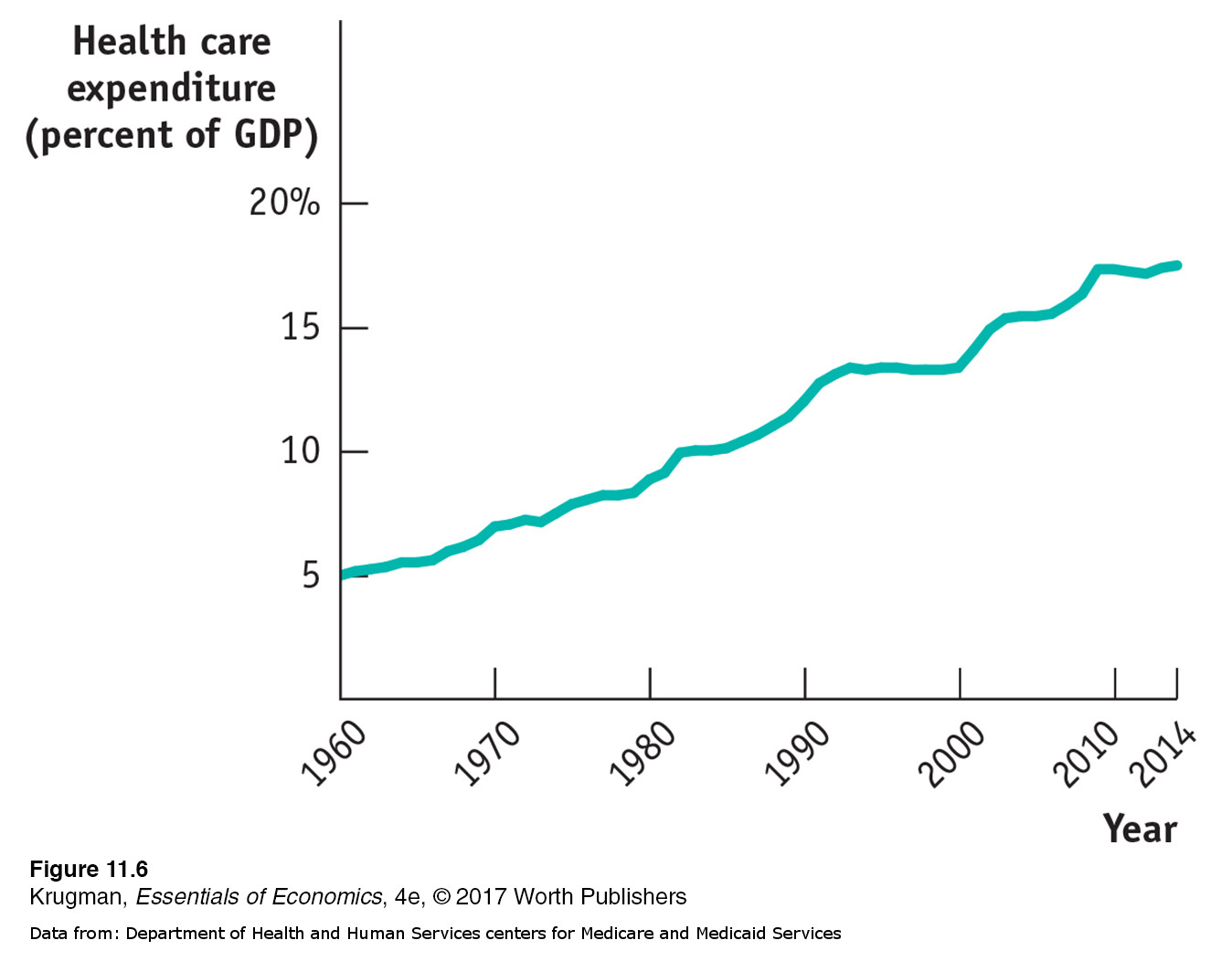

Lying behind the growing number of uninsured, in turn, were sharply rising premiums for health insurance, reflecting rapid growth in overall health care costs. Figure 11-6 shows overall U.S. spending on health care as a percentage of GDP, a measure of the nation’s total income, since the 1960s. As you can see, health spending has tripled as a share of income since 1965; this increase in spending explains why health insurance has become more expensive. Similar trends can be observed in other countries.

The consensus of health experts is that the rise in health care spending is a result of medical progress. As medical science advances, once untreatable conditions become treatable—

The combination of a rising number of uninsured and rising costs led to many calls for health care reform in the United States. And in 2010, Congress passed the Affordable Care Act (ACA) which took full effect in 2014. It was the largest expansion of the American welfare state since the creation of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965. It had two major objectives: covering the uninsured and cost control.

Covering the Uninsured To understand the logic of the ACA, consider the problem facing one major category of uninsured Americans: the many people who seek coverage in the individual insurance market but are turned down because they have preexisting medical conditions, which insurance companies fear could lead to large future expenses. Lou Vincent, from this chapter’s opening story, was one of those people. He was denied coverage for years because he had Type II diabetes. How could insurance be made available to such people?

One answer would be regulations requiring that insurance companies offer the same policies to everyone, regardless of medical history—

To make community rating work, sick and healthy alike need to buy health insurance—

It’s important to realize that this system is like a three-

Cost Control But will the ACA control costs? In itself, the expansion of coverage will raise health care spending, although not by as much as you might think. The uninsured are by and large relatively young, and the young have relatively low health care costs. (The elderly are already covered by Medicare.) The question is whether the reform can succeed in reducing the rate of growth of health costs over time.

The ACA’s promise to control costs starts from the premise that the U.S. medical system, as currently constituted, has skewed incentives that waste resources. Because most care is paid for by insurance, doctors and patients have little incentive to worry about costs. In fact, because health care providers are generally paid for each procedure they perform, there’s a financial incentive to provide additional care—

The ACA attempts to correct these skewed incentives in a variety of ways, from stricter oversight of reimbursements, to linking payments to a procedure’s medical value, to paying health care providers for improved health outcomes rather than the number of procedures, and by limiting the tax deductibility of employment-

Results So Far Important provisions of the Affordable Care Act took effect at the beginning of 2014 and by 2015 it was possible to get an initial view of its results.

These include a drop in the unemployed percentage of the working-

In terms of costs, several measures of health cost growth slowed substantially after 2010. Most notably, Medicare spending per beneficiary, which grew 7% a year from 2000 to 2010, grew only 1% per year from 2010 to 2014. Growth in premiums for employer-

Overall, as of 2015 health reform seemed to be working more or less as intended. It remains to be seen how it will perform over the longer term.

ECONOMICS in Action

What Medicaid Does

| interactive activity

| interactive activity

Do social insurance programs actually help their beneficiaries? The answer isn’t always as obvious as you might think. Take the example of Medicaid, which provides health insurance to low-

Testing such assertions is tricky. You can’t just compare people who are on Medicaid with people who aren’t, since the program’s beneficiaries differ in many ways from those who aren’t on the program. And we don’t normally get to do controlled experiments in which otherwise comparable groups receive different government benefits.

Once in a while, however, events provide the equivalent of a controlled experiment—

So what were the results? It turned out that Medicaid made a big difference. Those on Medicaid received

60% more mammograms

35% more outpatient care

30% more hospital care

20% more cholesterol checks

Medicaid recipients were also

70% more likely to have a consistent source of care

45% more likely to have had a Pap test within the last year (for women)

40% less likely to need to borrow money or skip payment on other bills because of medical expenses

25% percent more likely to report themselves in “good” or “excellent” health

15% more likely to use prescription drugs

15% more likely to have had a blood test for high blood sugar or diabetes

10% percent less likely to screen positive for depression

In short, Medicaid led to major improvements in access to medical care and the well-

Quick Review

Health insurance satisfies an important need because expensive medical treatment is unaffordable for most families. Private health insurance has an inherent problem: those who buy insurance are disproportionately sicker than the average person, which drives up costs and premiums, leading more healthy people to forgo insurance, further driving up costs and premiums and ultimately leading private insurance companies to fail. Screening by insurance companies reduces the problem, and employment-

based health insurance, the way most Americans are covered, avoids it altogether. The majority of Americans not covered by private insurance are covered by Medicare, which is a non-

means- tested single- payer system for those over 65, and Medicaid, which is means- tested. Compared to other wealthy countries, the United States depends more heavily on private health insurance, has higher health care spending per person, higher administrative costs, and higher drug prices, but without clear evidence of better health outcomes.

Health care costs everywhere are increasing rapidly due to medical progress. The 2010 ACA legislation was designed to address the large and growing share of American uninsured and to reduce the rate of growth of health care spending.

Check Your Understanding11-3

Question 11.7

1. If you are enrolled in a four-

The program benefits you and your parents because the pool of all college students contains a representative mix of healthy and less healthy people, rather than a selected group of people who want insurance because they expect to pay high medical bills. In that respect, this insurance is like employment-

Question 11.8

2. According to its critics, what accounts for the higher costs of the U.S. health care system compared to those of other wealthy countries?

According to critics, part of the reason the U.S. health care system is so much more expensive than those of other countries is its fragmented nature. Since each of the many insurance companies has significant administrative (overhead) costs—

Solutions appear at back of book.