12.5 International Imbalances

An open economy is an economy that trades goods and services with other countries.

The United States is an open economy: an economy that trades goods and services with other countries. There have been times when that trade was more or less balanced—

A country runs a trade deficit when the value of goods and services bought from foreigners is more than the value of goods and services it sells to them. It runs a trade surplus when the value of goods and services bought from foreigners is less than the value of the goods and services it sells to them.

In 2014, the United States ran a big trade deficit—

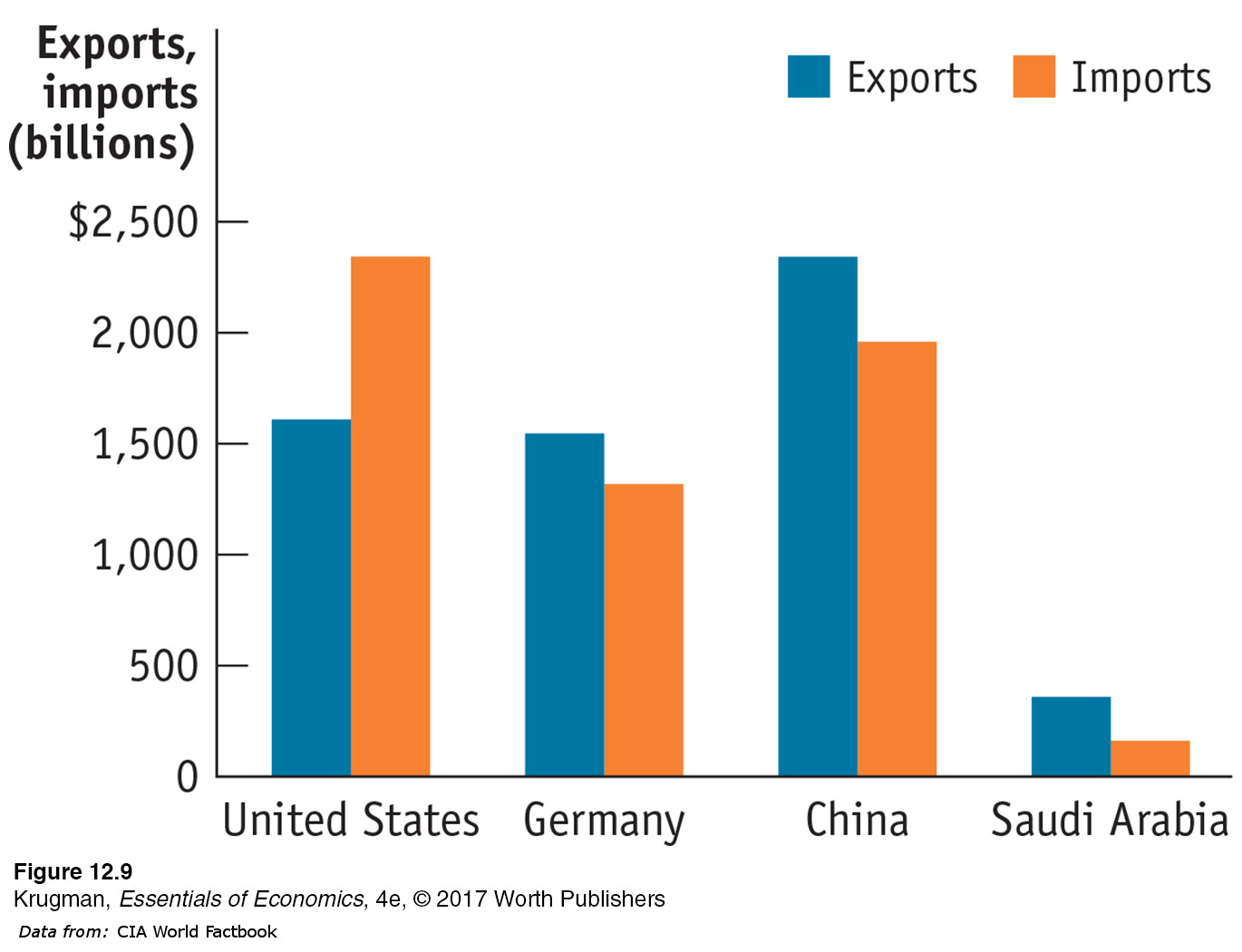

Figure 12-9 shows the exports and imports of goods for several important economies in 2014. As you can see, the United States imported much more than it exported, but Germany, China, and Saudi Arabia did the reverse: they each ran a trade surplus. A country runs a trade surplus when the value of the goods and services it buys from the rest of the world is smaller than the value of the goods and services it sells abroad. Was America’s trade deficit a sign that something was wrong with our economy—

No, not really. Trade deficits and their opposite, trade surpluses, are macroeconomic phenomena. They’re the result of situations in which the whole is very different from the sum of its parts. You might think that countries with highly productive workers or widely desired products and services to sell run trade surpluses but countries with unproductive workers or poor-

356

In Chapter 2 we learned that international trade is the result of comparative advantage: countries export goods they’re relatively good at producing and import goods they’re not as good at producing. That’s why the United States exports wheat and imports coffee. What the concept of comparative advantage doesn’t explain, however, is why the value of a country’s imports is sometimes much larger than the value of its exports, or vice versa.

So what does determine whether a country runs a trade surplus or a trade deficit? In Chapter 20 we’ll learn the surprising answer: the determinants of the overall balance between exports and imports lie in decisions about savings and investment spending—

ECONOMICS in Action

Spain’s Costly Surplus

| interactive activity

| interactive activity

In 1999 Spain took a momentous step: it gave up its national currency, the peseta, in order to adopt the euro, a shared currency intended to promote closer economic and political union among the nations of Europe. How did this affect Spain’s international trade?

1999-

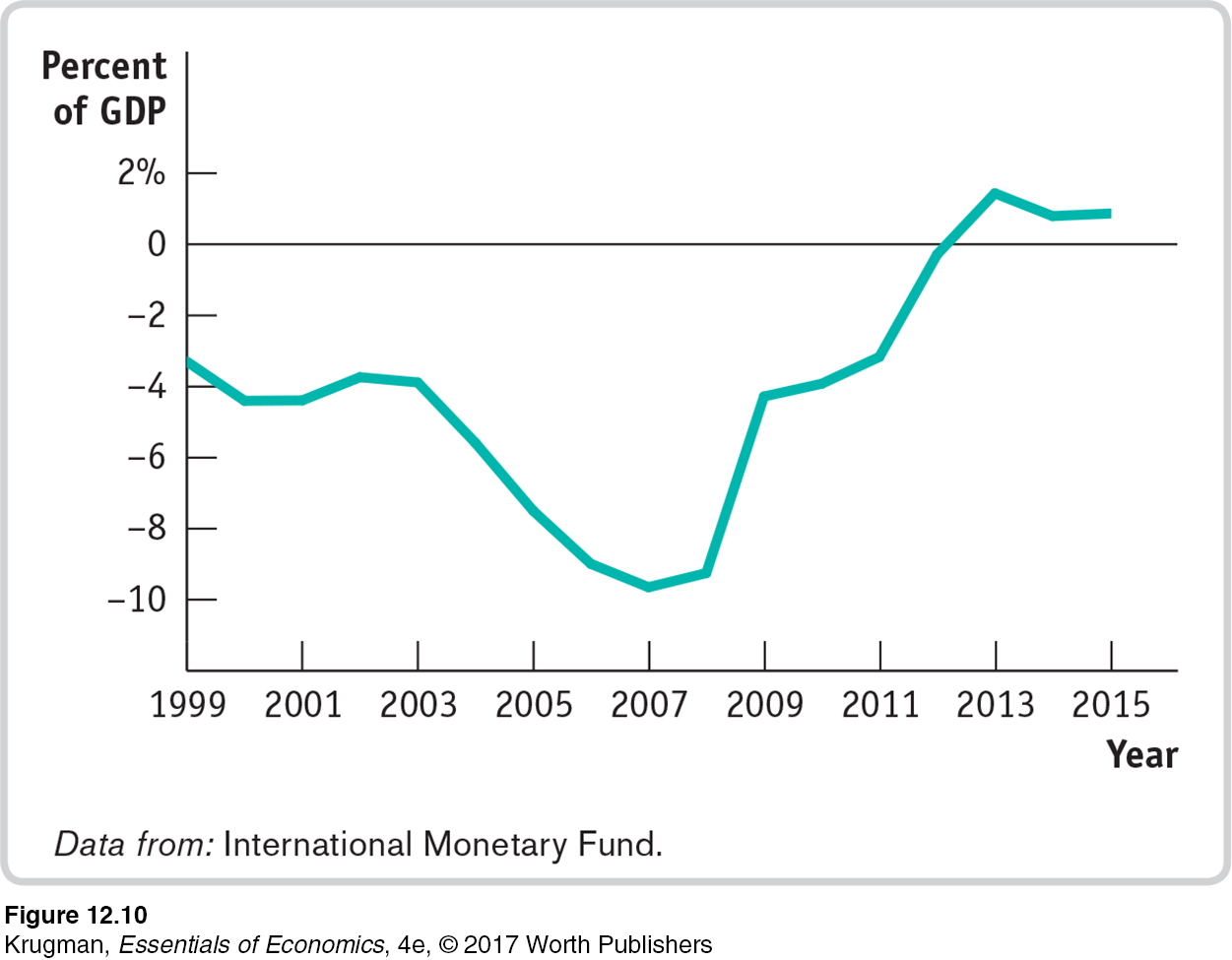

Figure 12-10 shows Spain’s current account balance—

Did this mean that Spain’s economy was doing badly in the mid-

357

Unfortunately, this epic boom eventually turned into an epic bust, and the inflows of foreign capital into Spain dried up. One consequence was that Spain could no longer run large trade deficits, and by 2013 was forced into running a surplus. Another consequence was a severe recession, leading to very high unemployment—

Quick Review

Comparative advantage can explain why an open economy exports some goods and services and imports others, but it can’t explain why a country imports more than it exports, or vice versa.

Trade deficits and trade surpluses are macroeconomic phenomena, determined by decisions about investment spending and savings.

Check Your Understanding 12-

Question 12.8

1. Which of the following reflect comparative advantage, and which reflect macroeconomic forces?

Thanks to the development of huge oil sands in the province of Alberta, Canada has become an exporter of oil and an importer of manufactured goods.

This situation reflects comparative advantage. Canada’s comparative advantage results from the development of oil—

Canada now has an abundance of oil. Like many consumer goods, the Apple iPod is assembled in China, although many of the components are made in other countries.

This situation reflects comparative advantage. China’s comparative advantage results from an abundance of labor; China is good at labor-

intensive activities such as assembly. Since 2002, Germany has been running huge trade surpluses, exporting much more than it imports.

This situation reflects macroeconomic forces. Germany has been running a huge trade surplus because of underlying decisions regarding savings and investment spending with its savings in excess of its investment spending.

The United States, which had roughly balanced trade in the early 1990s, began running large trade deficits later in the decade, as the technology boom took off.

This situation reflects macroeconomic forces. The United States was able to begin running a large trade deficit because the technology boom made the United States an attractive place to invest, with investment spending outstripping U.S. savings.

Solutions appear at back of book.