14.2 Inflation and Deflation

As we’ve seen, monetary officials are perennially divided between doves and hawks—

The Level of Prices Doesn’t Matter . . .

The most common complaint about inflation, an increase in the price level, is that it makes everyone poorer—

An example of this kind of currency conversion happened in 2002, when France, like a number of other European countries, replaced its national currency, the franc, with the euro. People turned in their franc coins and notes, and received euro coins and notes in exchange, at a rate of precisely 6.55957 francs per euro. At the same time, all contracts were restated in euros at the same rate of exchange. For example, if a French citizen had a home mortgage debt of 500,000 francs, this became a debt of 500,000/6.55957 = 76,224.51 euros. If a worker’s contract specified that he or she should be paid 100 francs per hour, it became a contract specifying a wage of 100/6.55957 = 15.2449 euros per hour, and so on.

You could imagine doing the same thing here, replacing the dollar with a “new dollar” at a rate of exchange of, say, 7 to 1. If you owed $140,000 on your home, that would become a debt of 20,000 new dollars. If you had a wage rate of $14 an hour, it would become 2 new dollars an hour, and so on. This would bring the overall U.S. price level back to about what it was in 1962, when John F. Kennedy was president.

The real wage is the wage rate divided by the price level.

So would everyone be richer as a result because prices would be only one-

Real income is income divided by the price level.

393

Conversely, the rise in prices that has actually taken place since the early 1960s hasn’t made America poorer because it has also raised incomes by the same amount: real incomes—incomes divided by the price level—

The moral of this story is that the level of prices doesn’t matter: the United States would be no richer than it is now if the overall level of prices were still as low as it was in 1961; conversely, the rise in prices over the past 50 years hasn’t made us poorer.

. . . But the Rate of Change of Prices Does

The conclusion that the level of prices doesn’t matter might seem to imply that the inflation rate doesn’t matter either. But that’s not true.

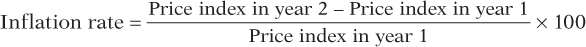

To see why, it’s crucial to distinguish between the level of prices and the inflation rate: the percent increase in the overall level of prices per year. Recall that the inflation rate is defined as follows:

Figure 14-11 highlights the difference between the price level and the inflation rate in the United States over the last half-

394

Economists believe that high rates of inflation impose significant economic costs. The most important of these costs are shoe-

Shoe-

The upcoming Economics in Action describes how Israelis spent a lot of time at the bank during the periods of high inflation rates that afflicted Israel in 1984–1985. During the most famous of all inflations, the German hyperinflation of 1921–1923, merchants employed runners to take their cash to the bank many times a day to convert it into something that would hold its value, such as a stable foreign currency. In each case, in an effort to avoid having the purchasing power of their money eroded, people used up valuable resources, such as time for Israeli citizens and the labor of those German runners, that could have been used productively elsewhere. During the German hyperinflation, so many banking transactions were taking place that the number of employees at German banks nearly quadrupled—

More recently, Brazil experienced hyperinflation during the early 1990s; during that episode, the Brazilian banking sector grew so large that it accounted for 15% of GDP, more than twice the size of the financial sector in the United States measured as a share of GDP. The large increase in the Brazilian banking sector needed to cope with the consequences of inflation represented a loss of real resources to its society.

Shoe-

Increased costs of transactions caused by inflation are known as shoe-

The menu cost is the real cost of changing a listed price.

Menu Costs In a modern economy, most of the things we buy have a listed price. There’s a price listed under each item on a supermarket shelf, a price printed on the back of a book, and a price listed for each dish on a restaurant’s menu. Changing a listed price has a real cost, called a menu cost. For example, to change prices in a supermarket requires sending clerks through the store to change the listed price under each item. In the face of inflation, of course, firms are forced to change prices more often than they would if the aggregate price level was more or less stable. This means higher costs for the economy as a whole.

In times of very high inflation, menu costs can be substantial. During the Brazilian inflation of the early 1990s, for instance, supermarket workers reportedly spent half of their time replacing old price stickers with new ones. When inflation is high, merchants may decide to stop listing prices in terms of the local currency and use either an artificial unit—

395

Menu costs are also present in low-

Unit-

Unit-

This role of the dollar as a basis for contracts and calculation is called the unit-

Unit-

During the 1970s, when the United States had relatively high inflation, the distorting effects of inflation on the tax system were a serious problem. Some businesses were discouraged from productive investment spending because they found themselves paying taxes on phantom gains. Meanwhile, some unproductive investments became attractive because they led to phantom losses that reduced tax bills. When inflation fell in the 1980s—

396

Winners and Losers from Inflation

As we’ve just learned, a high inflation rate imposes overall costs on the economy. In addition, inflation can produce winners and losers within the economy. The main reason inflation sometimes helps some people while hurting others is that economic transactions often involve contracts that extend over a period of time, such as loans, and these contracts are normally specified in nominal—

The interest rate on a loan is the price, calculated as a percentage of the amount borrowed, that lenders charge borrowers for the use of their savings for one year.

In the case of a loan, the borrower receives a certain amount of funds at the beginning, and the loan contract specifies the interest rate on the loan and when it must be paid off. The interest rate is the return a lender receives for allowing borrowers the use of their savings for one year, calculated as a percentage of the amount borrowed.

The nominal interest rate is the interest rate expressed in dollar terms.

The real interest rate is the nominal interest rate minus the rate of inflation.

But what that dollar is worth in real terms—

When a borrower and a lender enter into a loan contract, the contract is normally written in dollar terms—

In modern America, home mortgages are the most important source of gains and losses from inflation. Americans who took out mortgages in the early 1970s quickly found their real payments reduced by higher-

Because gains for some and losses for others result from inflation that is either higher or lower than expected, yet another problem arises: uncertainty about the future inflation rate discourages people from entering into any form of long-

One last point: unexpected deflation—

397

Inflation Is Easy; Disinflation Is Hard

Disinflation is the process of bringing the inflation rate down.

There is not much evidence that a rise in the inflation rate from, say, 2% to 5% would do a great deal of harm to the economy. Still, policy makers generally move forcefully to bring inflation back down when it creeps above 2% or 3%. Why? Because experience shows that bringing the inflation rate down—

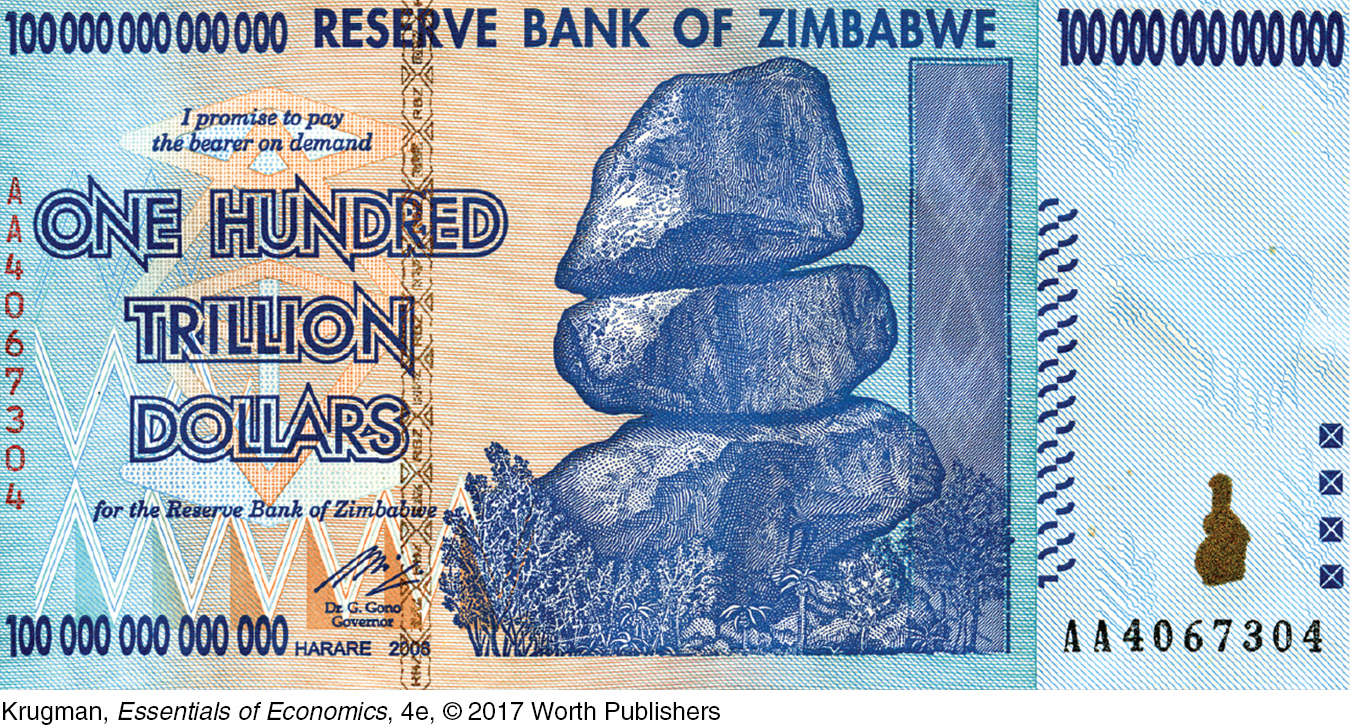

Figure 14-12 shows what happened during two major episodes of disinflation in the United States, in the mid-

According to many economists, these periods of high unemployment that temporarily depressed the economy were necessary to reduce inflation that had become deeply embedded in the economy. The best way to avoid having to put the economy through a wringer to reduce inflation, however, is to avoid having a serious inflation problem in the first place. So policy makers respond forcefully to signs that inflation may be accelerating as a form of preventive medicine for the economy.

ECONOMICS in Action

Israel’s Experience with Inflation

| interactive activity

| interactive activity

It’s often hard to see the costs of inflation clearly because serious inflation problems are often associated with other problems that disrupt economic life, notably war or political instability (or both). In the mid-

398

As it happens, one of the authors spent a month visiting at Tel Aviv University at the height of the inflation, so we can give a first-

First, the shoe-

Second, although menu costs weren’t that visible to a visitor, what you could see were the efforts businesses made to minimize them. For example, restaurant menus often didn’t list prices. Instead, they listed numbers that you had to multiply by another number, written on a chalkboard and changed every day, to figure out the price of a dish.

Finally, it was hard to make decisions because prices changed so much and so often. It was a common experience to walk out of a store because prices were 25% higher than at one’s usual shopping destination, only to discover that prices had just been increased 25% there, too.

Quick Review

The real wage and real income are unaffected by the level of prices.

Inflation, like unemployment, is a major concern of policy makers—

so much so that in the past they have accepted high unemployment as the price of reducing inflation. While the overall level of prices is irrelevant, high rates of inflation impose real costs on the economy: shoe-

leather costs, menu costs, and unit- of- account costs. The interest rate is the return a lender receives for use of his or her funds for a year. The real interest rate is equal to the nominal interest rate minus the inflation rate. As a result, unexpectedly high inflation helps borrowers and hurts lenders. With high and uncertain inflation, people often avoid long-

term investments. Disinflation is very costly, so policy makers try to avoid situations of high inflation in the first place.

Check Your Understanding 14-

Question 14.7

1. The widespread use of technology has revolutionized the banking industry, making it much easier for customers to access and manage their assets. Does this mean that the shoe-

Shoe-

Question 14.8

2. Most people in the United States have grown accustomed to a modest inflation rate of around 2% to 3%. Who would gain and who would lose if inflation unexpectedly came to a complete stop over the next 15 or 20 years?

If inflation came to an unexpected and complete stop over the next 15 or 20 years, the inflation rate would be zero, which of course is less than the expected inflation rate of 2% to 3%. Because the real interest rate is the nominal interest rate minus the inflation rate, the real interest rate on a loan would be higher than expected, and lenders would gain at the expense of borrowers. Borrowers would have to repay their loans with funds that have a higher real value than had been expected.

Solutions appear at back of book.