4.6 Price Floors

The minimum wage is a legal floor on the wage rate, which is the market price of labor.

Sometimes governments intervene to push market prices up instead of down. Price floors have been widely legislated for agricultural products, such as wheat and milk, as a way to support the incomes of farmers. Historically, there were also price floors—

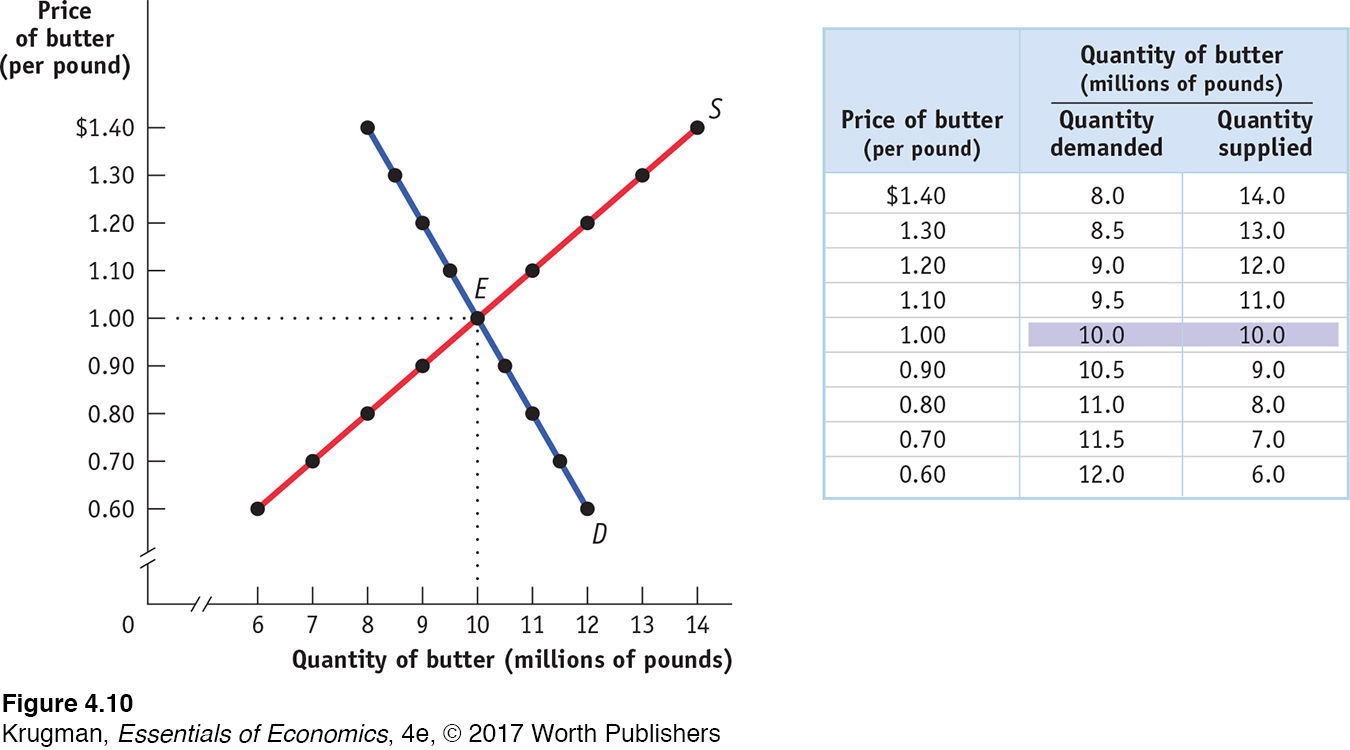

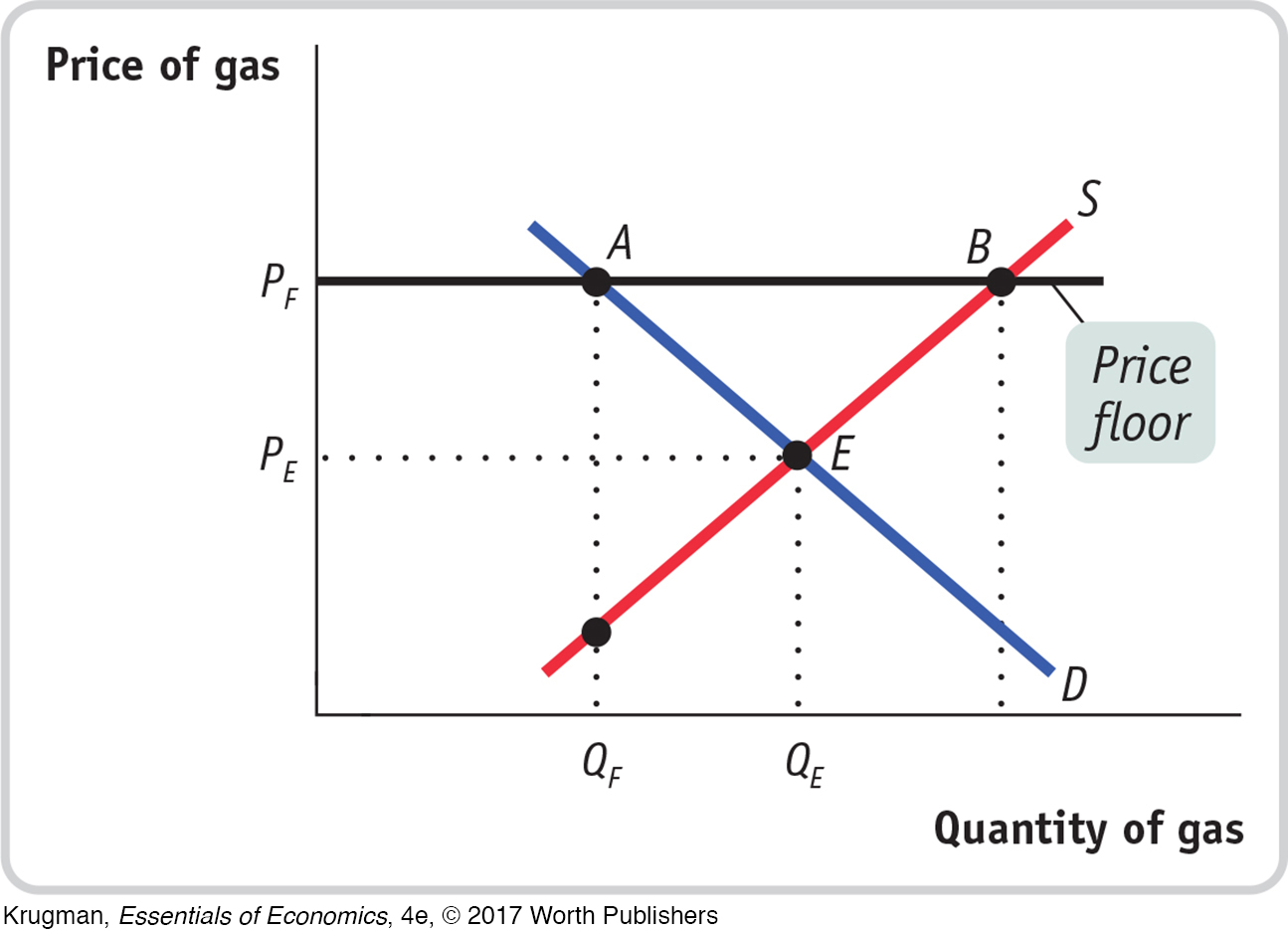

Just like price ceilings, price floors are intended to help some people but generate predictable and undesirable side effects. Figure 4-10 shows hypothetical supply and demand curves for butter. Left to itself, the market would move to equilibrium at point E, with 10 million pounds of butter bought and sold at a price of $1 per pound.

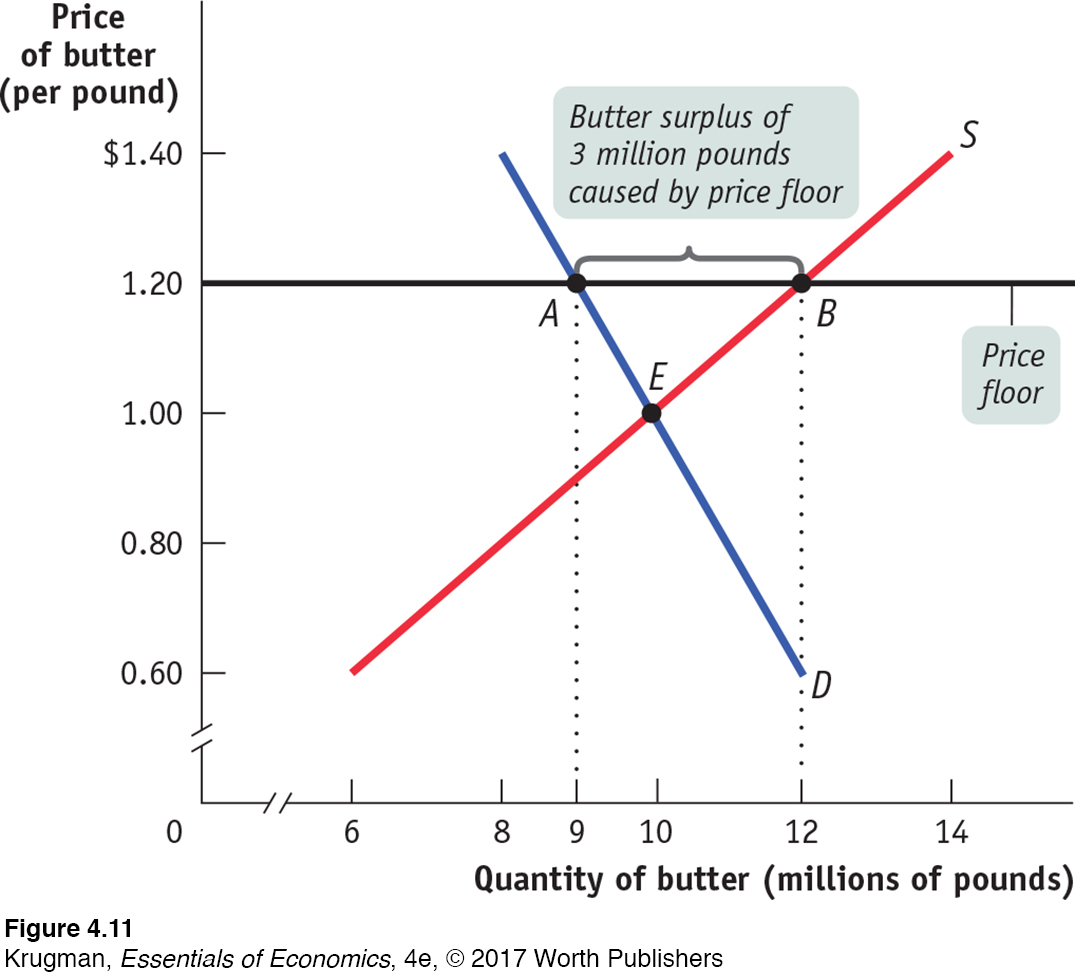

Now suppose that the government, in order to help dairy farmers, imposes a price floor on butter of $1.20 per pound. Its effects are shown in Figure 4-11, where the line at $1.20 represents the price floor. At a price of $1.20 per pound, producers would want to supply 12 million pounds (point B on the supply curve) but consumers would want to buy only 9 million pounds (point A on the demand curve). So the price floor leads to a persistent surplus of 3 million pounds of butter.

Does a price floor always lead to an unwanted surplus? No. Just as in the case of a price ceiling, the floor may not be binding—

But suppose that a price floor is binding: what happens to the unwanted surplus? The answer depends on government policy. In the case of agricultural price floors, governments buy up unwanted surplus. As a result, the U.S. government has at times found itself warehousing thousands of tons of butter, cheese, and other farm products. (The European Commission, which administers price floors for a number of European countries, once found itself the owner of a so-

Some countries pay exporters to sell products at a loss overseas; this is standard procedure for the European Union. The United States gives surplus food away to schools, which use the products in school lunches. In some cases, governments have actually destroyed the surplus production. To avoid the problem of dealing with the unwanted surplus, the U.S. government typically pays farmers not to produce the products at all.

When the government is not prepared to purchase the unwanted surplus, a price floor means that would-

How a Price Floor Causes Inefficiency

The persistent surplus that results from a price floor creates missed opportunities—

It creates deadweight loss by reducing the quantity transacted to below the efficient level.

It leads to an inefficient allocation of sales among sellers.

It leads to a waste of resources.

It leads to sellers providing an inefficiently high quality level.

In addition to inefficiency, like a price ceiling, a price floor leads to illegal behavior as people break the law to sell below the legal price.

Inefficiently Low Quantity Because a price floor raises the price of a good to consumers, it reduces the quantity of that good demanded; because sellers can’t sell more units of a good than buyers are willing to buy, a price floor reduces the quantity of a good bought and sold below the market equilibrium quantity and leads to a deadweight loss. Notice that this is the same effect as a price ceiling. You might be tempted to think that a price floor and a price ceiling have opposite effects, but both have the effect of reducing the quantity of a good bought and sold (as you can see in the following Pitfalls).

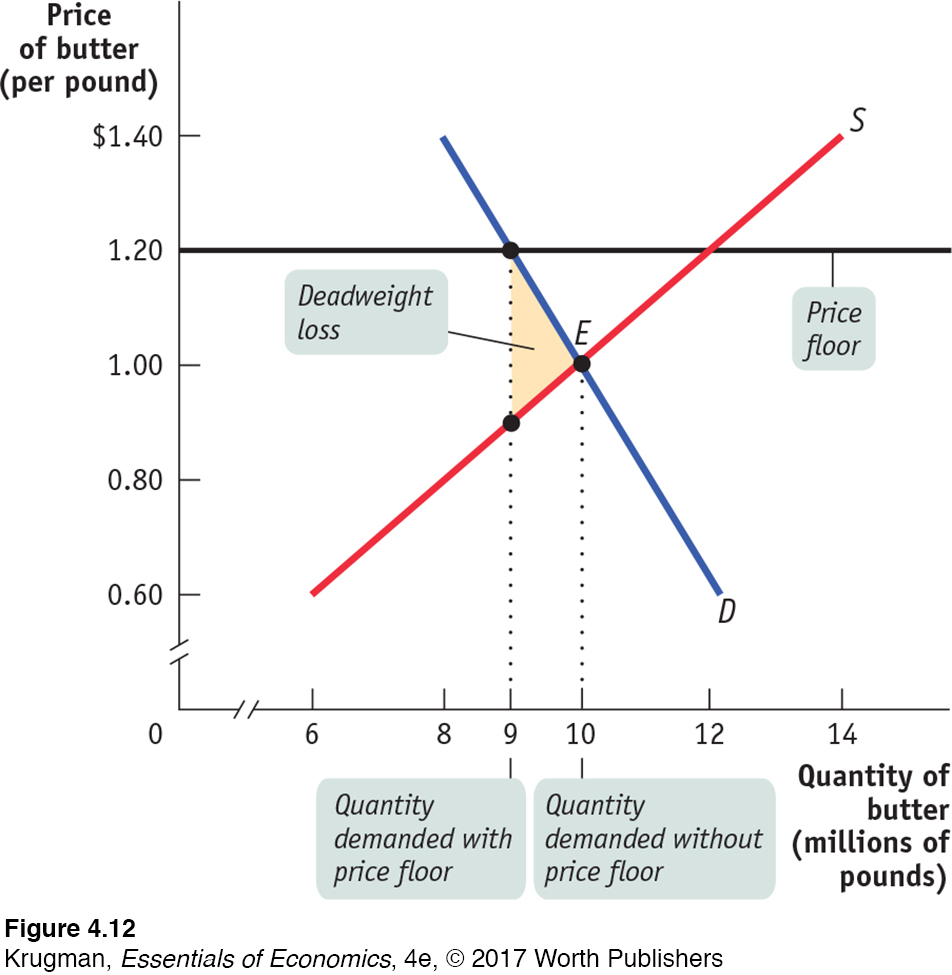

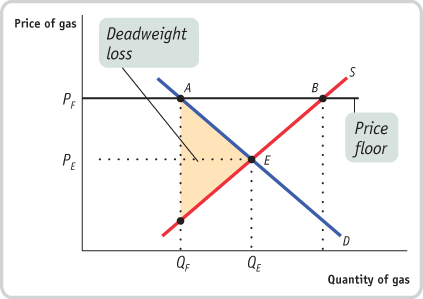

Since the equilibrium of an efficient market maximizes the sum of consumer and producer surplus, a price floor that reduces the quantity below the equilibrium quantity reduces total surplus. Figure 4-12 shows the implications for total surplus of a price floor on the price of butter. Total surplus is the sum of the area above the supply curve and below the demand curve. By reducing the quantity of butter sold, a price floor causes a deadweight loss equal to the area of the shaded triangle in the figure. As in the case of a price ceiling, however, deadweight loss is only one of the forms of inefficiency that the price control creates.

PITFALLS

CEILINGS, FLOORS, AND QUANTITIES

A price ceiling pushes the price of a good down. A price floor pushes the price of a good up. So it’s easy to assume that the effects of a price floor are the opposite of the effects of a price ceiling. In particular, if a price ceiling reduces the quantity of a good bought and sold, doesn’t a price floor increase the quantity?

No, it doesn’t. In fact, both floors and ceilings reduce the quantity bought and sold. Why? When the quantity of a good supplied isn’t equal to the quantity demanded, the actual quantity sold is determined by the “short side” of the market—

Price floors can lead to inefficient allocation of sales among sellers: sellers who are willing to sell at the lowest price are unable to make sales while sales go to sellers who are only willing to sell at a higher price.

Inefficient Allocation of Sales Among Sellers Like a price ceiling, a price floor can lead to inefficient allocation—in this case, an inefficient allocation of sales among sellers: sellers who are willing to sell at the lowest price are unable to make sales, while sales go to sellers who are only willing to sell at a higher price.

One illustration of the inefficient allocation of selling opportunities caused by a price floor is the problem of unemployment and the black market for labor among the young in many European countries—

Either unemployed or underemployed in dead-

The inefficiency of unemployment and underemployment is compounded as a generation of young people is unable to get adequate job training, develop careers, and save for their future. These young people are also more likely to engage in crime. And many of these countries have seen their best and brightest young people emigrate, leading to a permanent reduction in the future performance of their economies.

Wasted Resources Also like a price ceiling, a price floor generates inefficiency by wasting resources. The most graphic examples involve government purchases of the unwanted surpluses of agricultural products caused by price floors. The surplus production is sometimes destroyed, which is pure waste; in other cases, the stored produce goes, as officials euphemistically put it, “out of condition” and must be thrown away.

Price floors also lead to wasted time and effort. Consider the minimum wage. Would-

Inefficiently High Quality Again like price ceilings, price floors lead to inefficiency in the quality of goods produced.

Price floors often lead to inefficiency in that goods of inefficiently high quality are offered: sellers offer high-

We saw that when there is a price ceiling, suppliers produce products that are of inefficiently low quality: buyers prefer higher-

How can this be? Isn’t high quality a good thing? Yes, but only if it is worth the cost. Suppose that suppliers spend a lot to make goods of very high quality but that this quality isn’t worth much to consumers, who would rather receive the money spent on that quality in the form of a lower price. This represents a missed opportunity: suppliers and buyers could make a mutually beneficial deal in which buyers got goods of lower quality for a much lower price.

A good example of the inefficiency of excessive quality comes from the days when transatlantic airfares were set artificially high by international treaty. Forbidden to compete for customers by offering lower ticket prices, airlines instead offered expensive services, like lavish in-

Since the deregulation of U.S. airlines in the 1970s, American passengers have experienced a large decrease in ticket prices accompanied by a decrease in the quality of in-

Illegal Activity In addition to the four inefficiencies we analyzed, like price ceilings, price floors provide incentives for illegal activity. For example, in countries where the minimum wage is far above the equilibrium wage rate, workers desperate for jobs sometimes agree to work off the books for employers who conceal their employment from the government—

So Why Are There Price Floors?

To sum up, a price floor creates various negative side effects:

A persistent surplus of the good

Inefficiency arising from the persistent surplus in the form of inefficiently low quantity (deadweight loss), inefficient allocation of sales among sellers, wasted resources, and an inefficiently high level of quality offered by suppliers

The temptation to engage in illegal activity, particularly bribery and corruption of government officials

GLOBAL

COMPARISON

Check Out Our Low, Low Wages!

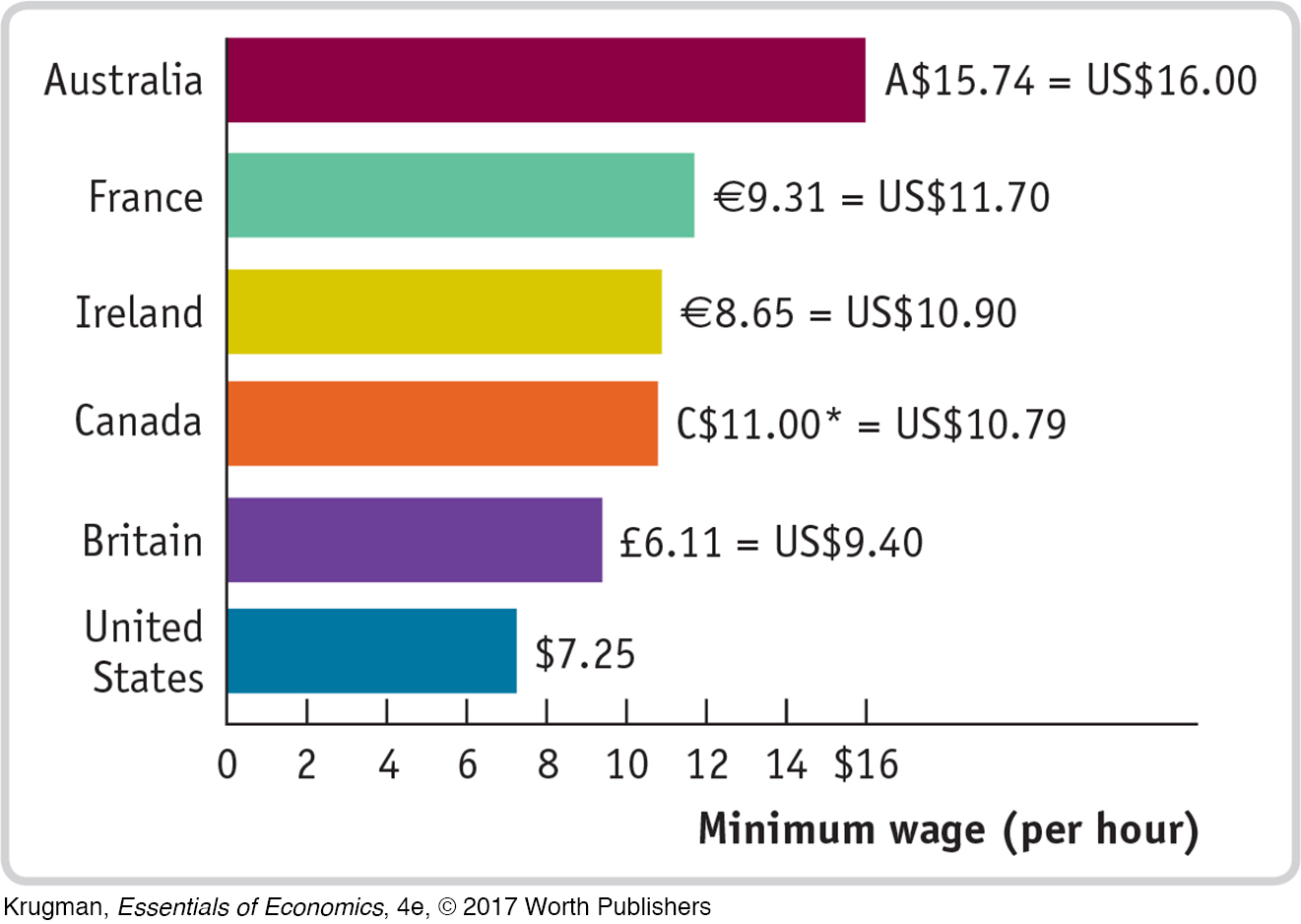

The minimum wage rate in the United States, as you can see in this graph, is actually quite low compared with that in other rich countries. Since minimum wages are set in national currency—

Data from: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

*The Canadian minimum wage varies by province from C$9.95 to C$11.00.

So why do governments impose price floors when they have so many negative side effects? The reasons are similar to those for imposing price ceilings. Government officials often disregard warnings about the consequences of price floors either because they believe that the relevant market is poorly described by the supply and demand model or, more often, because they do not understand the model. Above all, just as price ceilings are often imposed because they benefit some influential buyers of a good, price floors are often imposed because they benefit some influential sellers.

ECONOMICS in Action

The Rise and Fall of the Unpaid Intern

| interactive activity

| interactive activity

The best-

Internships are temporary work positions typically reserved for younger workers still in college or recent graduates. The sluggish U.S. economy of recent years has produced poor job prospects for workers 20 to 24 years old. The unemployment rate for this age group was almost 12% at the start of 2014. One result of this has been a rise in the availability of internships, which look increasingly appealing to enthusiastic young workers unable to find well-

Internships fall into two broad categories: paid interns, who are formally hired as temporary workers, and must be paid at least the minimum wage, and unpaid interns, who perform tasks but are not legally designated employees and aren’t covered by minimum wage laws. Because internships offer the promise of valuable work experience and credentials that can later prove very valuable, young workers are often willing to accept them at a low wage or even no wage. According to Robert Shindell, an executive at the consulting firm Intern Bridge, more than a million American students a year do internships; a fifth of those positions pay zero and provide no course credits.

Not surprisingly, some companies are tempted to use unpaid interns to perform work that in reality has little or no educational value but that directly benefits the company.

To guard against such practices, the Department of Labor (DOL), the federal agency that monitors compliance with minimum wage laws, issued several criteria in 2010 to help companies determine whether their unpaid internships are legally exempt from minimum wage requirements. Among them are: (1) Is the experience primarily for the benefit of the intern and not the employer? (2) Is the internship comparable to training offered by an educational environment? and (3) Is there no displacement of a regular employee by the intern? If the answer to such questions is yes, then the DOL considers the internship to be a form of education that is exempt from minimum wage laws. However, if the answer to any of the questions is no, then the DOL may determine that the unpaid internship violates minimum wage laws, in which case, the position must either be converted into a paid internship that pays at least the minimum wage or be eliminated.

In 2012 and 2013, a spate of lawsuits brought by former unpaid interns claiming they were cheated out of wages brought the matter to public attention. In 2013, the movie company Fox Searchlight Pictures was found guilty of breaking federal minimum wage laws for employing two interns at zero pay. A common thread in these complaints is that interns were assigned “grunt work” that had no educational value—

As a result, many lawyers who advise companies on labor laws have been advising companies to either pay their interns minimum wage or shut down their internships. While some have axed their programs altogether, others—

Quick Review

The most familiar price floor is the minimum wage. Price floors are also commonly imposed on agricultural goods.

A price floor above the equilibrium price benefits successful sellers but causes predictable adverse effects such as a persistent surplus, which leads to four kinds of inefficiencies: deadweight loss from inefficiently low quantity, inefficient allocation of sales among sellers, wasted resources, and inefficiently high quality.

Price floors encourage illegal activity, such as workers who work off the books, often leading to official corruption.

Check Your Understanding 4-3

Question 4.6

1. The state legislature mandates a price floor for gasoline of PF per gallon. Assess the following statements and illustrate your answer using the figure provided.

Proponents of the law claim it will increase the income of gas station owners. Opponents claim it will hurt gas station owners because they will lose customers.

Some gas station owners will benefit from getting a higher price. QF indicates the sales made by these owners. But some will lose; there are those who make sales at the market equilibrium price of PE but do not make sales at the regulated price of PF. These missed sales are indicated on the graph by the fall in the quantity demanded along the demand curve, from point E to point A.

Proponents claim consumers will be better off because gas stations will provide better service. Opponents claim consumers will be generally worse off because they prefer to buy gas at cheaper prices.

Those who buy gas at the higher price of PF will probably receive better service; this is an example of inefficiently high quality caused by a price floor as gas station owners compete on quality rather than price. But opponents are correct to claim that consumers are generally worse off—

those who buy at PF would have been happy to buy at PE, and many who were willing to buy at a price between PE and PF are now unwilling to buy. This is indicated on the graph by the fall in the quantity demanded along the demand curve, from point E to point A. Proponents claim that they are helping gas station owners without hurting anyone else. Opponents claim that consumers are hurt and will end up doing things like buying gas in a nearby state or on the black market.

Proponents are wrong because consumers and some gas station owners are hurt by the price floor, which creates “missed opportunities”—desirable transactions between consumers and station owners that never take place. The deadweight loss, the amount of total surplus lost because of missed opportunities, is indicated by the shaded area in the accompanying figure. Moreover, the inefficiency of wasted resources arises as consumers spend time and money driving to other states. The price floor also tempts people to engage in black market activity. With the price floor, only QF units are sold. But at prices between PE and PF, there are drivers who cumulatively want to buy more than QF and owners who are willing to sell to them, a situation likely to lead to illegal activity.

Solutions appear at back of book.