Chapter Introduction

Macroeconomics: The Big Picture

What You Will Learn in this Chapter

- What makes macroeconomics different from microeconomics

- What a business cycle is and why policy makers seek to diminish the severity of business cycles

- How long-run economic growth determines a country’s standard of living

- The meaning of inflation and deflation and why price stability is preferred

- The importance of open-economy macroeconomics and how economies interact through trade deficits and trade surpluses

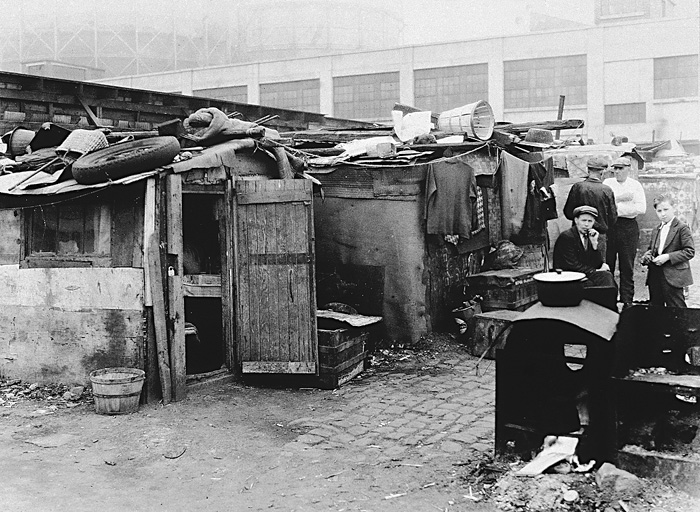

Hoovervilles

TODAY MANY PEOPLE ENJOY walking, biking, and horseback riding in New York’s Central Park. But in 1932 there were also many people living there: Central Park contained one of the “Hoovervilles”—shantytowns—that had sprung up all across America as a result of a catastrophic economic slump that started in 1929, leaving millions of workers out of work, reduced to standing in breadlines or selling apples on street corners. The U.S. economy would stage a partial recovery beginning in 1933, but joblessness stayed high throughout the 1930s. The whole period would come to be known as the Great Depression.

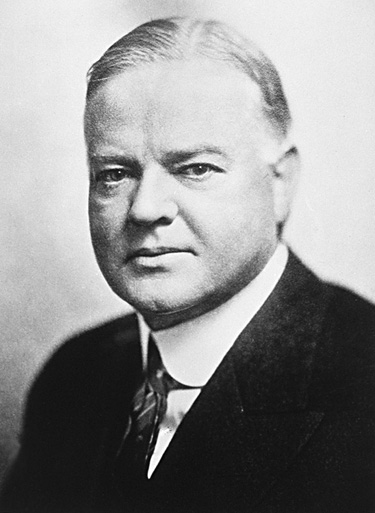

Why Hoovervilles? The shantytowns got their derisive name from Herbert Hoover, who had been elected president in 1928—and who lost his bid for reelection because many Americans blamed him for the Depression. Hoover began his career as an engineer, and until he became president he had a reputation as a can-do, highly competent manager. But when the Depression struck, neither he nor his economic advisers had any idea what to do.

Hoover’s cluelessness was no accident. At the time of the Great Depression, microeconomics, which is concerned with the consumption and production decisions of individual consumers and producers and with the allocation of scarce resources among industries, was already a well-developed branch of economics. But macroeconomics, which focuses on the behavior of the economy as a whole, was still in its infancy.

What happened between 1929 and 1933, and on a smaller scale on many other occasions (most recently between 2007 and 2009), was a blow to the economy as a whole. At any given moment there are always some industries laying off workers. For example, the number of independent record stores in America fell almost 30% between 2003 and 2007, as consumers turned to online purchases. But workers who lost their jobs at record stores had a good chance of finding new jobs elsewhere, because other industries were expanding even as record stores shut their doors. In the early 1930s, however, there were no expanding industries: everything was headed downward.

Macroeconomics came into its own as a branch of economics during the Great Depression. Economists realized that they needed to understand the nature of the catastrophe that had overtaken the United States and much of the rest of the world in order to extricate themselves as well as to learn how to avoid such catastrophes in the future. To this day, the effort to understand economic slumps and find ways to prevent them is at the core of macroeconomics. Over time, however, macroeconomics has broadened its reach to encompass a number of other subjects, such as long-run economic growth, inflation, and open-economy macroeconomics.

This chapter offers an overview of macroeconomics. We start with a general description of the difference between macroeconomics and microeconomics, then briefly describe some of the field’s major concerns.