The Business Cycle

The Great Depression was by far the worst economic crisis in U.S. history. But although the economy managed to avoid catastrophe for the rest of the twentieth century, it has experienced many ups and downs.

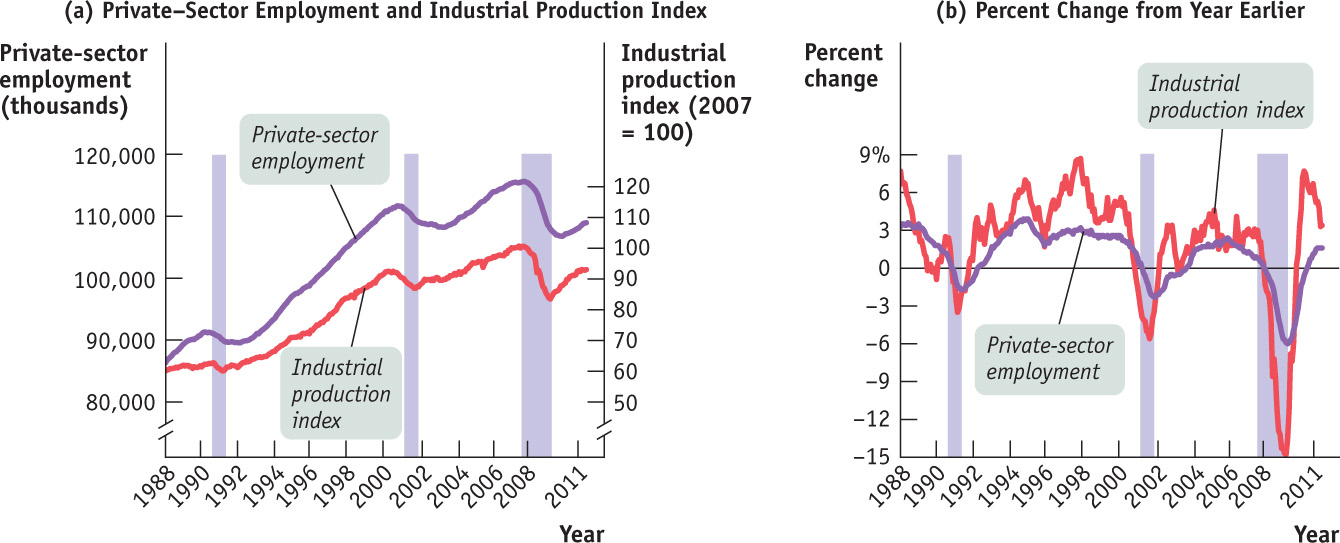

It’s true that the ups have consistently been bigger than the downs: a chart of any of the major numbers used to track the U.S. economy shows a strong upward trend over time. For example, panel (a) of Figure 10-2 shows total U.S. private-sector employment (the total number of jobs offered by private businesses) measured along the left vertical axis, with the data from 1988 to 2011 given by the purple line. The graph also shows the index of industrial production (a measure of the total output of U.S. factories) measured along the right vertical axis, with the data from 1988 to 2011 given by the red line. Both private-sector employment and industrial production were much higher at the end of this period than at the beginning, and in most years both measures rose.

FIGURE 10-2 Growth, Interrupted, 1988–2011

But they didn’t rise steadily. As you can see from the figure, there were three periods—in the early 1990s, in the early 2000s, and again beginning in late 2007—when both employment and industrial output stumbled. Panel (b) emphasizes these stumbles by showing the rate of change of employment and industrial production over the previous year. For example, the percent change in employment for December 2007 was 0.7, because employment in December 2007 was 0.7% higher than it had been in December 2006. The three big downturns stand out clearly. What’s more, a detailed look at the data makes it clear that in each period the stumble wasn’t confined to only a few industries: in each downturn, just about every sector of the U.S. economy cut back on production and on the number of people employed.

The economy’s forward march, in other words, isn’t smooth. And the uneven pace of the economy’s progress, its ups and downs, is one of the main preoccupations of macroeconomics.

Charting the Business Cycle

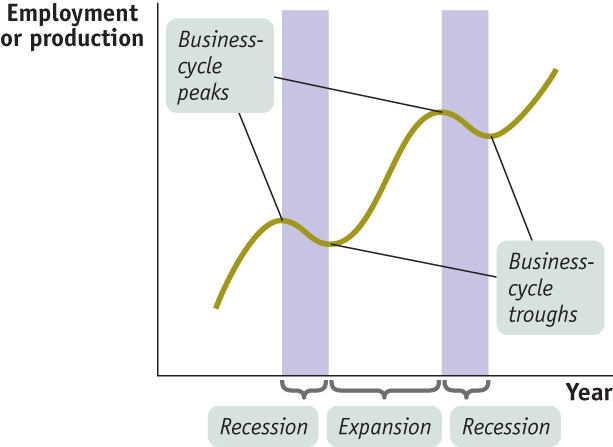

Figure 10-3 shows a stylized representation of the way the economy evolves over time. The vertical axis shows either employment or an indicator of how much the economy is producing, such as industrial production or real gross domestic product (real GDP), a measure of the economy’s overall output that we’ll learn about in the next chapter. As the data in Figure 10-2 suggest, these two measures tend to move together. Their common movement is the starting point for a major theme of macroeconomics: the economy’s alternation between short-run downturns and upturns.

FIGURE 10-3 The Business Cycle

Recessions, or contractions, are periods of economic downturn when output and employment are falling.

Expansions, or recoveries, are periods of economic upturn when output and employment are rising.

The business cycle is the short-run alternation between recessions and expansions.

The point at which the economy turns from expansion to recession is a business-cycle peak.

The point at which the economy turns from recession to expansion is a business-cycle trough.

A broad-based downturn, in which output and employment fall in many industries, is called a recession (sometimes referred to as a contraction). Recessions, as officially declared by the National Bureau of Economic Research, or NBER (see the upcoming For Inquiring Minds), are indicated by the shaded areas in Figure 10-2 . When the economy isn’t in a recession, when most economic numbers are following their normal upward trend, the economy is said to be in an expansion (sometimes referred to as a recovery). The alternation between recessions and expansions is known as the business cycle. The point in time at which the economy shifts from expansion to recession is known as a business-cycle peak; the point at which the economy shifts from recession to expansion is known as a business-cycle trough.

The business cycle is an enduring feature of the economy. Table 10-2 shows the official list of business-cycle peaks and troughs. As you can see, there have been recessions and expansions for at least the past 155 years. Whenever there is a prolonged expansion, as there was in the 1960s and again in the 1990s, books and articles come out proclaiming the end of the business cycle. Such proclamations have always proved wrong: The cycle always comes back. But why does it matter?

TABLE 10-2 The History of the Business Cycle

| Business-Cycle Peak | Business-Cycle Trough |

|---|---|

| no prior data available | December 1854 |

| June 1857 | December 1858 |

| October 1860 | June 1861 |

| April 1865 | December 1867 |

| June 1869 | December 1870 |

| October 1873 | March 1879 |

| March 1882 | May 1885 |

| March 1887 | April 1888 |

| July 1890 | May 1891 |

| January 1893 | June 1894 |

| December 1895 | June 1897 |

| June 1899 | December 1900 |

| September 1902 | August 1904 |

| May 1907 | June 1908 |

| January 1910 | January 1912 |

| January 1913 | December 1914 |

| August 1918 | March 1919 |

| January 1920 | July 1921 |

| May 1923 | July 1924 |

| October 1926 | November 1927 |

| August 1929 | March 1933 |

| May 1937 | June 1938 |

| February 1945 | October 1945 |

| November 1948 | October 1949 |

| July 1953 | May 1954 |

| August 1957 | April 1958 |

| April 1960 | February 1961 |

| December 1969 | November 1970 |

| November 1973 | March 1975 |

| January 1980 | July 1980 |

| July 1981 | November 1982 |

| July 1990 | March 1991 |

| March 2001 | November 2001 |

| December 2007 | June 2009 |

The Pain of Recession

Not many people complain about the business cycle when the economy is expanding. Recessions, however, create a great deal of pain.

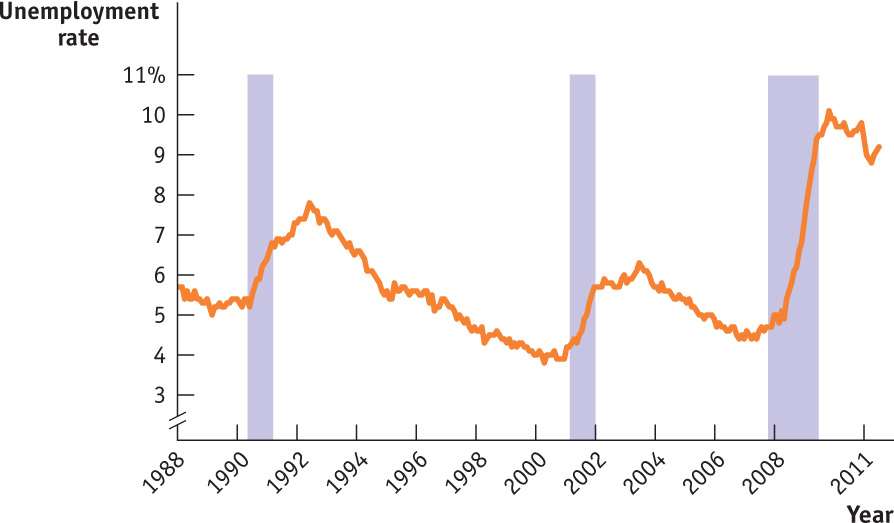

The most important effect of a recession is its effect on the ability of workers to find and hold jobs. The most widely used indicator of conditions in the labor market is the unemployment rate. We’ll explain how that rate is calculated in Chapter 12, but for now it’s enough to say that a high unemployment rate tells us that jobs are scarce and a low unemployment rate tells us that jobs are easy to find. Figure 10-4 shows the unemployment rate from 1988 to 2011. As you can see, the U.S. unemployment rate surged during and after each recession but eventually fell during periods of expansion. The rising unemployment rate in 2008 was a sign that a new recession might be under way, which was later confirmed by the NBER to have begun in December 2007.

FIGURE 10-4 The U.S. Unemployment Rate, 1988–2011

Because recessions cause many people to lose their jobs and also make it hard to find new ones, recessions hurt the standard of living of many families. Recessions are usually associated with a rise in the number of people living below the poverty line, an increase in the number of people who lose their houses because they can’t afford the mortgage payments, and a fall in the percentage of Americans with health insurance coverage.

Defining Recessions and Expansions

Some readers may be wondering exactly how recessions and expansions are defined. The answer is that there is no exact definition!

In many countries, economists adopt the rule that a recession is a period of at least two consecutive quarters (a quarter is three months) during which the total output of the economy shrinks. The two-consecutive-quarters requirement is designed to avoid classifying brief hiccups in the economy’s performance, with no lasting significance, as recessions.

Sometimes, however, this definition seems too strict. For example, an economy that has three months of sharply declining output, then three months of slightly positive growth, then another three months of rapid decline, should surely be considered to have endured a nine-month recession.

In the United States, we try to avoid such misclassifications by assigning the task of determining when a recession begins and ends to an independent panel of experts at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). This panel looks at a variety of economic indicators, with the main focus on employment and production. But, ultimately, the panel makes a judgment call.

Sometimes this judgment is controversial. In fact, there is lingering controversy over the 2001 recession. According to the NBER, that recession began in March 2001 and ended in November 2001 when output began rising. Some critics argue, however, that the recession really began several months earlier, when industrial production began falling. Other critics argue that the recession didn’t really end in 2001 because employment continued to fall and the job market remained weak for another year and a half.

You should not think, however, that workers are the only group that suffers during a recession. Recessions are also bad for firms: like employment and wages, profits suffer during recessions, with many small businesses failing, and do well during expansions.

All in all, then, recessions are bad for almost everyone. Can anything be done to reduce their frequency and severity?

Taming the Business Cycle

Modern macroeconomics largely came into being as a response to the worst recession in history—the 43-month downturn that began in 1929 and continued into 1933, ushering in the Great Depression. The havoc wreaked by the 1929–1933 recession spurred economists to search both for understanding and for solutions: they wanted to know how such things could happen and how to prevent them.

As we explained earlier in this chapter, the work of John Maynard Keynes, published during the Great Depression, suggested that monetary and fiscal policies could be used to mitigate the effects of recessions, and to this day governments turn to Keynesian policies when recession strikes. Later work, notably that of another great macroeconomist, Milton Friedman, led to a consensus that it’s important to rein in booms as well as to fight slumps. So modern policy makers try to “smooth out” the business cycle. They haven’t been completely successful, as a look at Figure 10-2 makes clear. It’s widely believed, however, that policy guided by macroeconomic analysis has helped make the economy more stable.

Although the business cycle is one of the main concerns of macroeconomics and historically played a crucial role in fostering the development of the field, macroeconomists are also concerned with other issues. We turn next to the question of long-run growth.

International Business Cycles

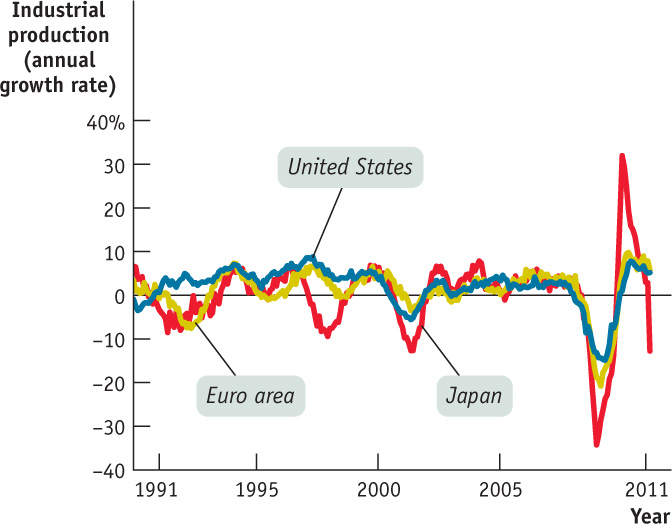

This figure shows the annual rate of growth in industrial production—the percent change since the same month the previous year—for three economies from 1991 to 2011: the United States, Japan, and the euro area, the group of European countries that have adopted the euro as their common currency. Do other economies have business cycles similar to those in the United States?

The answer, which is clear from the figure, is yes. Furthermore, business cycles in different economies are often, although not always, synchronized. The U.S. recession of 2001 was paralleled by recessions in both the euro area and Japan; the Great Recession of 2007–2009 was a severe slump around the world, not just in America. But not all business cycles are international phenomena. Japan suffered a fairly severe recession in 1998, even as the United States and European economies continued to expand.

Comparing Recessions

The alternation of recessions and expansions seems to be an enduring feature of economic life. However, not all business cycles are created equal. In particular, some recessions have been much worse than others.

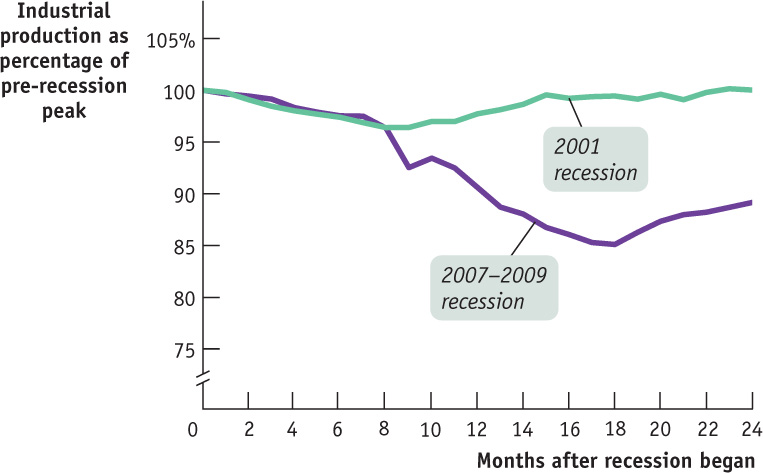

Let’s compare the two most recent recessions: the 2001 recession and the Great Recession of 2007–2009. These recessions differed in duration: the first lasted only eight months, the second more than twice as long. Even more important, however, they differed greatly in depth.

In Figure 10-5 we compare the depth of the recessions by looking at what happened to industrial production over the months after the recession began. In each case, production is measured as a percentage of its level at the recession’s start. Thus the line for the 2007–2009 recession shows that industrial production eventually fell to about 85% of its initial level.

FIGURE 10-5 Two Recessions

Clearly, the 2007–2009 recession hit the economy vastly harder than the 2001 recession. Indeed, by comparison to many recessions, the 2001 slump was very mild.

Of course, this was no consolation to the millions of American workers who lost their jobs, even in that mild recession.

Quick Review

- The business cycle, the short-run alternation between recessions and expansions, is a major concern of modern macroeconomics.

- The point at which expansion shifts to recession is a business-cycle peak. The point at which recession shifts to expansion is a business-cycle trough.

Check Your Understanding 10-2

Question

Which of the following statements in incorrect?

A. B. C. D. We talk about business cycles for the economy as a whole because recessions and expansions are not confined to a few industries--they reflect downturns and upturns for the economy as a whole. The data clearly show that in the steep downturns, almost every sector of the economy reduces output and the number of people employed. Moreover, business cycles are an international phenomenon, sometimes moving in rough synchrony across countries.Question

Who gets hurt in a recession?

A. B. C. D. E. Recessions cause a great deal of pain across the entire society. They cause large numbers of workers to lose their jobs and make it hard to find new jobs. Recessions hurt the standard of living of many families and are usually associated with a rise in the number of people living below the poverty line, an increase in the number of people who lose their houses because they can't afford their mortgage payments, and a fall in the percentage of Americans with health insurance. Recessions also hurt the profits of firms.

Solutions appear at back of book.