Long-Run Economic Growth

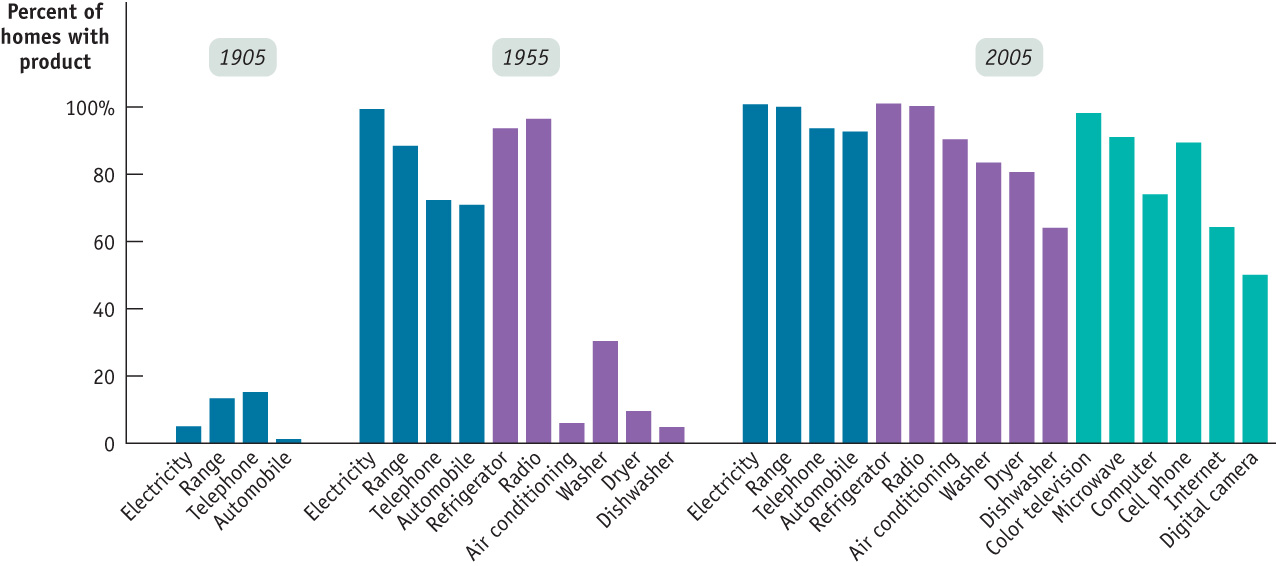

In 1955, Americans were delighted with the nation’s prosperity. The economy was expanding, consumer goods that had been rationed during World War II were available for everyone to buy, and most Americans believed, rightly, that they were better off than the citizens of any other nation, past or present. Yet by today’s standards, Americans were quite poor in 1955. Figure 10-6 shows the percentage of American homes equipped with a variety of appliances in 1905, 1955, and 2005: in 1955 only 37% of American homes contained washing machines and hardly anyone had air conditioning. And if we turn the clock back another half-century, to 1905, we find that life for many Americans was startlingly primitive by today’s standards.

FIGURE 10-6 The Fruits of Long-Run Growth in America

Long-run economic growth is the sustained upward trend in the economy’s output over time.

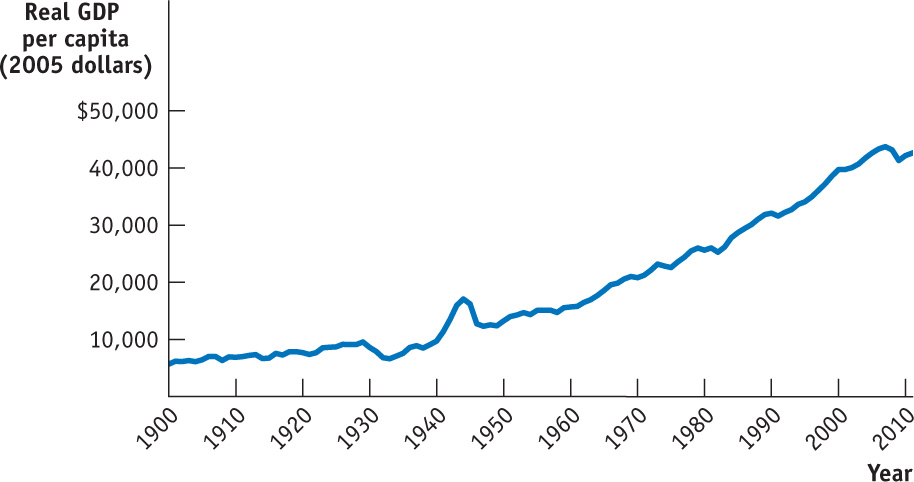

Why are the vast majority of Americans today able to afford conveniences that many Americans lacked in 1955? The answer is long-run economic growth, the sustained rise in the quantity of goods and services the economy produces. Figure 10-7 shows the growth since 1900 in real GDP per capita, a measure of total output per person in the economy. The severe recession of 1929–1933 stands out, but business cycles between World War II and 2007 are almost invisible, dwarfed by the strong upward trend. Part of the long-run increase in output is accounted for by the fact that we have a growing population and workforce. But the economy’s overall production has increased by much more than the population. On average, in 2011 the U.S. economy produced about $48,000 worth of goods and services per person, about twice as much as in 1971, about three times as much as in 1951, and almost eight times as much as in 1900.

FIGURE 10-7 Growth, the Long View

Long-run economic growth is fundamental to many of the most pressing economic questions today. Responses to key policy questions, like the country’s ability to bear the future costs of government programs such as Social Security and Medicare, depend in part on how fast the U.S. economy grows over the next few decades. More broadly, the public’s sense that the country is making progress depends crucially on success in achieving long-run growth. When growth slows, as it did in the 1970s, it can help feed a national mood of pessimism. In particular, long-run growth per capita—a sustained upward trend in output per person—is the key to higher wages and a rising standard of living. A major concern of macroeconomics—and the theme of Chapter 13—is trying to understand the forces behind long-run growth.

When did Long-Run Growth Start?

Today, the United States is much richer than it was in 1955; in 1955 it was much richer than it had been in 1905. But how did 1855 compare with 1805? Or 1755? How far back does long-run economic growth go?

The answer is that long-run growth is a relatively modern phenomenon. The U.S. economy was already growing steadily by the mid-nineteenth century—think railroads. But if you go back to the period before 1800, you find a world economy that grew extremely slowly by today’s standards. Furthermore, the population grew almost as fast as the economy, so there was very little increase in output per person. According to the economic historian Angus Maddison, from 1000 to 1800, real aggregate output around the world grew less than 0.2% per year, with population rising at about the same rate.

Economic stagnation meant unchanging living standards. For example, information on prices and wages from sources such as monastery records shows that workers in England weren’t significantly better off in the early eighteenth century than they had been five centuries earlier. And it’s a good bet that they weren’t much better off than Egyptian peasants in the age of the pharaohs. However, long-run economic growth has increased significantly since 1800. In the last 50 years or so, real GDP per capita has grown about 3.5% per year.

Thinkstock

Long-run growth is an even more urgent concern in poorer, less developed countries. In these countries, which would like to achieve a higher standard of living, the question of how to accelerate long-run growth is the central concern of economic policy.

As we’ll see, macroeconomists don’t use the same models to think about long-run growth that they use to think about the business cycle. It’s always important to keep both sets of models in mind, because what is good in the long run can be bad in the short run, and vice versa. For example, we’ve already mentioned the paradox of thrift: an attempt by households to increase their savings can cause a recession. But a higher level of savings plays a crucial role in encouraging long-run economic growth.

A Tale of Two Countries

Many countries have experienced long-run growth, but not all have done equally well. One of the most informative contrasts is between Canada and Argentina, two countries that, at the beginning of the twentieth century, seemed to be in a good economic position.

From today’s vantage point, it’s surprising to realize that Canada and Argentina looked rather similar before World War I. Both were major exporters of agricultural products; both attracted large numbers of European immigrants; both also attracted large amounts of European investment, especially in the railroads that opened up their agricultural hinterlands. Economic historians believe that the average level of per capita income was about the same in the two countries as late as the 1930s.

After World War II, however, Argentina’s economy performed poorly, largely due to political instability and bad macroeconomic policies. (Argentina experienced several periods of extremely high inflation, during which the cost of living soared.) Meanwhile, Canada made steady progress. Thanks to the fact that Canada has achieved sustained long-run growth since 1930, but Argentina has not, Canada today has almost as high a standard of living as the United States—and is about three times as high as Argentina’s.

Quick Review

- Because the U.S. economy has achieved long-run economic growth, Americans live much better than they did a half-century or more ago.

- Long-run economic growth is crucial for many economic concerns, such as a higher standard of living or financing government programs. It’s especially crucial for poorer countries.

Check Your Understanding 10-3

Question

Many poor countries have high rates of population growth. Which of the following correctly explains what this implies about the long-run growth rates of overall output that poor countries must achieve in order to generate a higher standard of living per person?

A. B. C. D. Countries with high rates of population growth will have to maintain higher growth rates of overall output than countries with low rates of population growth in order to achieve an increased standard of living per person because aggregate output will have to be divided among a larger number of people.Question

Argentina used to be as rich as Canada; now it's much poorer. Does this mean that Argentina is poorer than it was in the past?

A. B. No, Argentina is not poorer than it was in the past. Both Argentina and Canada have experienced longrun growth. However, after World War II, Argentina did not make as much progress as Canada, perhaps because of political instability and bad macroeconomic policies. Canada's economy grew much faster than Argentina's. Although Canada is now about three times as rich as Argentina, Argentina still had long-run growth of its economy.

Solutions appear at back of book.