Measuring the Macroeconomy

Almost all countries calculate a set of numbers known as the national income and product accounts. In fact, the accuracy of a country’s accounts is a remarkably reliable indicator of its state of economic development—in general, the more reliable the accounts, the more economically advanced the country. When international economic agencies seek to help a less developed country, typically the first order of business is to send a team of experts to audit and improve the country’s accounts.

The national income and product accounts, or national accounts, keep track of the flows of money between different sectors of the economy.

In the United States, these numbers are calculated by the Bureau of Economic Analysis, a division of the U.S. government’s Department of Commerce. The national income and product accounts, often referred to simply as the national accounts, keep track of the spending of consumers, sales of producers, business investment spending, government purchases, and a variety of other flows of money between different sectors of the economy.

Economists use the national accounts to measure the overall market value of the goods and services the economy produces. That measure has a name: it’s a country’s gross domestic product. But before we can formally define gross domestic product, or GDP, we have to examine an important distinction between classes of goods and services: the difference between final goods and services versus intermediate goods and services.

Gross Domestic Product

Final goods and services are goods and services sold to the final, or end, user.

Intermediate goods and services are goods and services—bought from one firm by another firm—that are inputs for production of final goods and services.

Gross domestic product, or GDP, is the total value of all final goods and services produced in the economy during a given year.

A consumer’s purchase of a new car from a dealer is one example of a sale of final goods and services: goods and services sold to the final, or end, user. But an automobile manufacturer’s purchase of steel from a steel foundry or glass from a glassmaker is an example of purchasing intermediate goods and services: goods and services that are inputs for production of final goods and services. In the case of intermediate goods and services, the purchaser—another firm—is not the final user.

Gross domestic product, or GDP, is the total value of all final goods and services produced in an economy during a given period, usually a year. In 2011 the GDP of the United States was $15,321 billion, or about $48,960 per person. If you are an economist trying to construct a country’s national accounts, one way to calculate GDP is to calculate it directly: survey firms and add up the total value of their production of final goods and services. We’ll explain in detail in the next section why intermediate goods, and some other types of goods as well, are not included in the calculation of GDP.

But adding up the total value of final goods and services produced is only one of three ways of calculating GDP. A second way is based on total spending on final goods and services. This second method adds aggregate spending on domestically produced final goods and services in the economy. The third way of calculating GDP is based on total income earned in the economy. Firms and the factors of production that they employ are owned by households. So firms must ultimately pay out what they earn to households. And so, a third way of calculating GDP is to sum the total factor income earned by households from firms in the economy.

Calculating GDP

We’ve just explained that there are in fact three methods for calculating GDP:

- adding up total value of all final goods and services produced

- adding up spending on all domestically produced goods and services

- adding to total factor income earned by households from firms in the economy

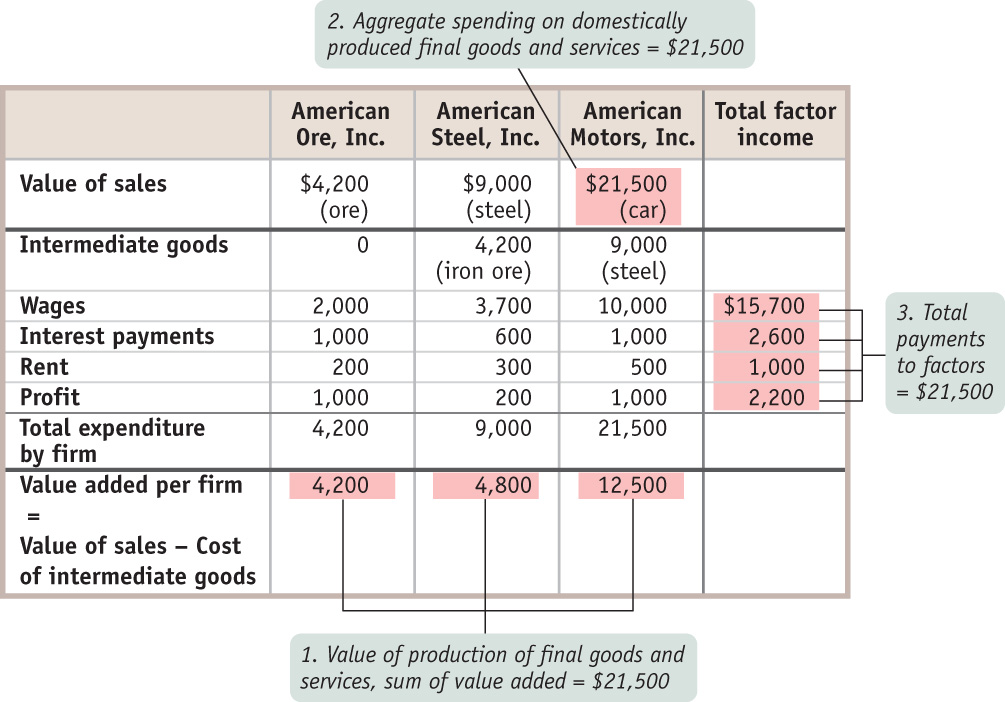

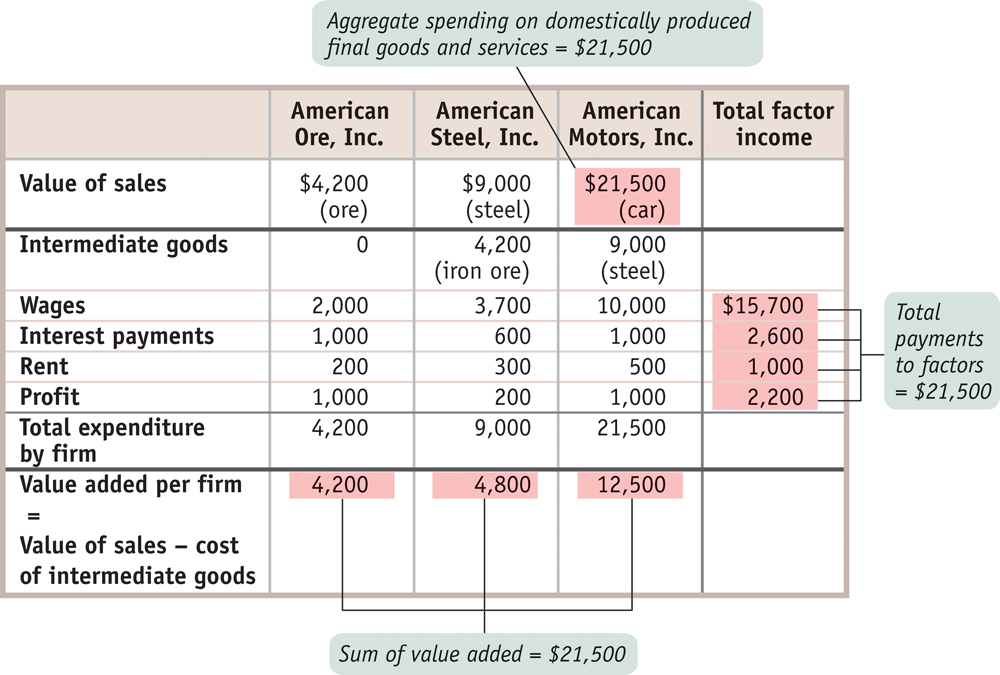

Government statisticians use all three methods. To illustrate how these three methods work, we will consider a hypothetical economy, shown in Figure 11-1. This economy consists of three firms—American Motors, Inc., which produces one car per year; American Steel, Inc., which produces the steel that goes into the car; and American Ore, Inc., which mines the iron ore that goes into the steel. So GDP is $21,500, the value of the one car per year the economy produces. Let’s look at how the three different methods of calculating GDP yield the same result.

FIGURE 11-1 Calculating GDP

Measuring GDP as the Value of Production of Final Goods and Services The first method for calculating GDP is to add up the value of all the final goods and services produced in the economy—a calculation that excludes the value of intermediate goods and services. Why are intermediate goods and services excluded? After all, don’t they represent a very large and valuable portion of the economy?

To understand why only final goods and services are included in GDP, look at the simplified economy described in Figure 11-1. Should we measure the GDP of this economy by adding up the total sales of the iron ore producer, the steel producer, and the auto producer? If we did, we would in effect be counting the value of the steel twice—once when it is sold by the steel plant to the auto plant, and again when the steel auto body is sold to a consumer as a finished car. And we would be counting the value of the iron ore three times—once when it is mined and sold to the steel company, a second time when it is made into steel and sold to the auto producer, and a third time when the steel is made into a car and sold to the consumer.

The value added of a producer is the value of its sales minus the value of its purchases of intermediate goods and services.

So counting the full value of each producer’s sales would cause us to count the same items several times and artificially inflate the calculation of GDP. For example, in Figure 11-1, the total value of all sales, intermediate and final, is $34,700: $21,500 from the sale of the car, plus $9,000 from the sale of the steel, plus $4,200 from the sale of the iron ore. Yet we know that GDP is only $21,500. The way we avoid double-counting is to count only each producer’s value added in the calculation of GDP: the difference between the value of its sales and the value of the intermediate goods and services it purchases from other businesses.

That is, at each stage of the production process we subtract the cost of inputs—the intermediate goods—at that stage. In this case, the value added of the auto producer is the dollar value of the cars it manufactures minus the cost of the steel it buys, or $12,500. The value added of the steel producer is the dollar value of the steel it produces minus the cost of the ore it buys, or $4,800. Only the ore producer, which we have assumed doesn’t buy any inputs, has value added equal to its total sales, $4,200. The sum of the three producers’ value added is $21,500, equal to GDP.

Measuring GDP as Spending on Domestically Produced Final Goods and Services Another way to calculate GDP is by adding up aggregate spending on domestically produced final goods and services. That is, GDP can be measured by the flow of funds into firms. Like the method that estimates GDP as the value of domestic production of final goods and services, this measurement must be carried out in a way that avoids double-counting. In terms of our steel and auto example, we don’t want to count both consumer spending on a car (represented in Figure 11-1 by $12,500, the sales price of the car) and the auto producer’s spending on steel (represented in Figure 11-1 by $9,000, the price of a car’s worth of steel). If we counted both, we would be counting the steel embodied in the car twice. We solve this problem by counting only the value of sales to final buyers, such as consumers, firms that purchase investment goods, the government, or foreign buyers. In other words, in order to avoid double-counting of spending, we omit sales of inputs from one business to another when estimating GDP using spending data. You can see from Figure 11-1 that aggregate spending on final goods and services—the finished car—is $21,500.

As we’ve already pointed out, the national accounts do include investment spending by firms as a part of final spending. That is, an auto company’s purchase of steel to make a car isn’t considered a part of final spending, but the company’s purchase of new machinery for its factory is considered a part of final spending. What’s the difference? Steel is an input that is used up in production; machinery will last for a number of years. Since purchases of capital goods that will last for a considerable time aren’t closely tied to current production, the national accounts consider such purchases a form of final sales.

Our Imputed Lives

An old line says that when a person marries the household cook, GDP falls. And it’s true: when someone provides services for pay, those services are counted as a part of GDP. But the services family members provide to each other are not. Some economists have produced alternative measures that try to “impute” the value of household work—that is, assign an estimate of what the market value of that work would have been if it had been paid for. But the standard measure of GDP doesn’t contain that imputation.

GDP estimates do, however, include an imputation for the value of “owner-occupied housing.” That is, if you buy the home you were formerly renting, GDP does not go down. It’s true that because you no longer pay rent to your landlord, the landlord no longer sells a service to you—namely, use of the house or apartment. But the statisticians make an estimate of what you would have paid if you rented whatever you live in, whether it’s an apartment or a house. For the purposes of the statistics, it’s as if you were renting your dwelling from yourself.

If you think about it, this makes a lot of sense. In a home-owning country like the United States, the pleasure we derive from our houses is an important part of the standard of living. So to be accurate, estimates of GDP must take into account the value of housing that is occupied by owners as well as the value of rental housing.

Measuring GDP as Factor Income Earned from Firms in the Economy A final way to calculate GDP is to add up all the income earned by factors of production from firms in the economy—the wages earned by labor; the interest paid to those who lend their savings to firms and the government; the rent earned by those who lease their land or structures to firms; and dividends, the profits paid to the shareholders, the owners of the firms’ physical capital. This is a valid measure because the money firms earn by selling goods and services must go somewhere; whatever isn’t paid as wages, interest, or rent is profit. Ultimately, profits are paid out to shareholders as dividends.

Figure 11-1 shows how this calculation works for our simplified economy. The shaded column at the far right shows the total wages, interest, and rent paid by all these firms as well as their total profit. Summing up all of these yields total factor income of $21,500—again, equal to GDP.

We won’t emphasize factor income as much as the other two methods of calculating GDP. It’s important to keep in mind, however, that all the money spent on domestically produced goods and services generates factor income to households.

What GDP Tells Us

Now we’ve seen the various ways that gross domestic product is calculated. But what does the measurement of GDP tell us?

The most important use of GDP is as a measure of the size of the economy, providing us a scale against which to measure the economic performance of other years or to compare the economic performance of other countries. For example, suppose you want to compare the economies of different nations. A natural approach is to compare their GDPs. In 2011, as we’ve seen, U.S. GDP was $15,321 billion, Japan’s GDP was $5,866 billion, and the combined GDP of the 27 countries that make up the European Union was $17,578 billion. This comparison tells us that Japan, although it has the world’s second-largest national economy, carries considerably less economic weight than does the United States. When taken in aggregate, Europe is America’s equal or superior.

Still, one must be careful when using GDP numbers, especially when making comparisons over time. That’s because part of the increase in the value of GDP over time represents increases in the prices of goods and services rather than an increase in output. For example, U.S. GDP was $7,415 billion in 1995 and had more than doubled to $15,321 billion by 2011. But the U.S. economy didn’t actually double in size over that period. To measure actual changes in aggregate output, we need a modified version of GDP that is adjusted for price changes, known as real GDP. We’ll see next how real GDP is calculated.

Creating the National Accounts

The national accounts, like modern macroeconomics, owe their creation to the Great Depression. As the economy plunged into depression, government officials found their ability to respond crippled not only by the lack of adequate economic theories but also by the lack of adequate information. All they had were scattered statistics: railroad freight car loadings, stock prices, and incomplete indexes of industrial production. They could only guess at what was happening to the economy as a whole.

In response to this perceived lack of information, the Department of Commerce commissioned Simon Kuznets, a young Russian-born economist, to develop a set of national income accounts. (Kuznets later won the Nobel Prize in economics for his work.) The first version of these accounts was presented to Congress in 1937 and in a research report titled National Income, 1929–35.

Kuznets’s initial estimates fell short of the full modern set of accounts because they focused on income, not production. The push to complete the national accounts came during World War II, when policy makers were in even more need of comprehensive measures of the economy’s performance. The federal government began issuing estimates of gross domestic product and gross national product in 1942.

In January 2000, in its publication Survey of Current Business, the Department of Commerce ran an article titled “GDP: One of the Great Inventions of the 20th Century.” This may seem a bit over the top, but national income accounting, invented in the United States, has since become a tool of economic analysis and policy making around the world.

Quick Review

- A country’s national income and product accounts, or national accounts, track flows of money among economic sectors.

- Gross domestic product, or GDP, can be calculated in three different ways: add up the value added by all firms; add up all spending on domestically produced final goods and services, or add up all factor income paid by firms. Intermediate goods and services are not included in the calculation of GDP.

Check Your Understanding 11-1

Question

Which of the following statements is TRUE?

A. B. C. D. Let's start by considering the relationship between the total value added of all domestically produced final goods and services and aggregate spending on domestically produced final goods and services. These two quantities are equal because every final good and service produced in the economy is either purchased by someone or added to inventories. And additions to inventories are counted as spending by firms. Next, consider the relationship between aggregate spending on domestically produced final goods and services and total factor income. These two quantities are equal because all spending that is channeled to firms to pay for purchases of domestically produced final goods and services is revenue for firms. Those revenues must be paid out by firms to their factors of production in the form of wages, profit, interest, and rent. Taken together, this means that all three methods of calculating GDP are equivalent.Question

Consider Figure 11-1 and suppose you mistakenly believed that total value added was $30,500, the sum of the sales price of a car and a car’s worth of steel. What items would you be counting twice?

A. B. C. D. You would be counting the value of the steel twice once as it was sold by American Steel to American Motors and once as part of the car sold by American Motors.

Solutions appear at back of book.