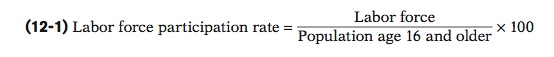

The Unemployment Rate

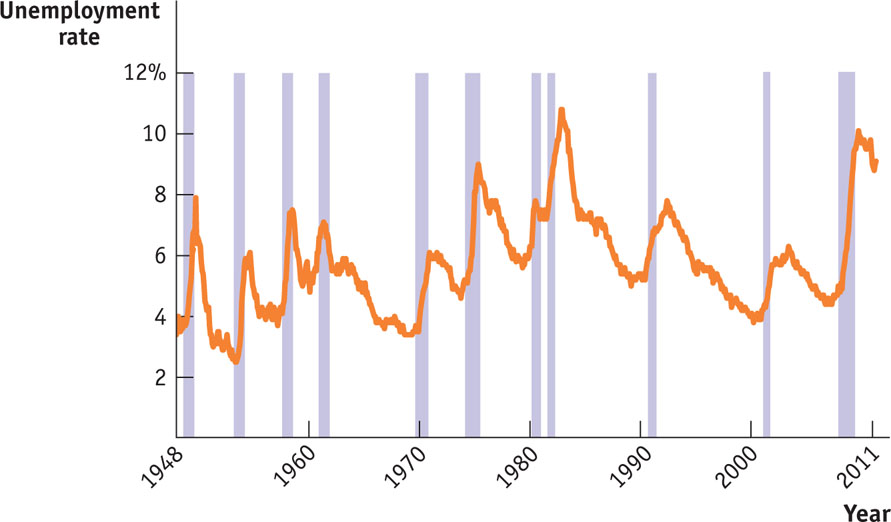

Britain had an unemployment rate of 7.7 percent in early 2011, up from just 5.7 percent in 2008. That was bad. But the U.S. unemployment rate was even worse. Figure 12-1 shows the U.S. unemployment rate from 1948 to mid-2011; as you can see, unemployment soared during the 2007–2009 recession and had fallen only modestly by 2011. What did the rise in the unemployment rate mean, and why was it such a big factor in people’s lives? To understand why policy makers pay so much attention to employment and unemployment, we need to understand how they are both defined and measured.

FIGURE 12-1 The U.S. Unemployment Rate, 1948–2011

Defining and Measuring Unemployment

Employment is the number of people currently employed in the economy, either full time or part time.

It’s easy to define employment: you’re employed if and only if you have a job. Employment is the total number of people currently employed, either full time or part time.

Unemployment, however, is a more subtle concept. Just because a person isn’t working doesn’t mean that we consider that person unemployed. For example, as of September 2012, there were 38.2 million retired workers in the United States receiving Social Security checks. Most of them were probably happy that they were no longer working, so we wouldn’t consider someone who has settled into a comfortable, well-earned retirement to be unemployed. There were also 7.9 million disabled U.S. workers receiving benefits because they were unable to work. Again, although they weren’t working, we wouldn’t normally consider them to be unemployed.

Unemployment is the number of people who are actively looking for work but aren’t currently employed.

The U.S. Census Bureau, the federal agency tasked with collecting data on unemployment, considers the unemployed to be those who are “jobless, looking for jobs, and available for work.” Retired people don’t count because they aren’t looking for jobs; the disabled don’t count because they aren’t available for work. More specifically, an individual is considered unemployed if he or she doesn’t currently have a job and has been actively seeking a job during the past four weeks. So unemployment is defined as the total number of people who are actively looking for work but aren’t currently employed.

The labor force is equal to the sum of employment and unemployment.

A country’s labor force is the sum of employment and unemployment—that is, of people who are currently working and people who are currently looking for work, respectively. The labor force participation rate, defined as the share of the working-age population that is in the labor force, is calculated as follows:

The labor force participation rate is the percentage of the population aged 16 or older that is in the labor force.

The unemployment rate, defined as the percentage of the total number of people in the labor force who are unemployed, is calculated as follows:

The unemployment rate is the percentage of the total number of people in the labor force who are unemployed.

To estimate the numbers that go into calculating the unemployment rate, the U.S. Census Bureau carries out a monthly survey called the Current Population Survey, which involves interviewing a random sample of 60,000 American families. People are asked whether they are currently employed. If they are not employed, they are asked whether they have been looking for a job during the past four weeks. The results are then scaled up, using estimates of the total population, to estimate the total number of employed and unemployed Americans.

The Significance of the Unemployment Rate

In general, the unemployment rate is a good indicator of how easy or difficult it is to find a job given the current state of the economy. When the unemployment rate is low, nearly everyone who wants a job can find one. In 2000, when the unemployment rate averaged 4%, jobs were so abundant that employers spoke of a “mirror test” for getting a job: if you were breathing (therefore your breath would fog a mirror), you could find work. By contrast, in 2010, with the unemployment rate above 9% all year, it was very hard to find work. In fact, there were almost five times as many Americans seeking work as there were job openings.

Although the unemployment rate is a good indicator of current labor market conditions, it’s not a literal measure of the percentage of people who want a job but can’t find one. That’s because in some ways the unemployment rate exaggerates the difficulty people have in finding jobs. But in other ways, the opposite is true—a low unemployment rate can conceal deep frustration over the lack of job opportunities.

Discouraged workers are nonworking people who are capable of working but have given up looking for a job given the state of the job market.

Marginally attached workers would like to be employed and have looked for a job in the recent past but are not currently looking for work.

Underemployment is the number of people who work part time because they cannot find full-time jobs.

How the Unemployment Rate Can Overstate the True Level of Unemployment If you are searching for work, it’s normal to take at least a few weeks to find a suitable job. Yet a worker who is quite confident of finding a job, but has not yet accepted a position, is counted as unemployed. As a consequence, the unemployment rate never falls to zero, even in boom times when jobs are plentiful. Even in the buoyant labor market of 2000, when it was easy to find work, the unemployment rate was still 4%. Later in this chapter, we’ll discuss in greater depth the reasons that measured unemployment persists even when jobs are abundant.

How the Unemployment Rate Can Understate the True Level of Unemployment Frequently, people who would like to work but aren’t working still don’t get counted as unemployed. In particular, an individual who has given up looking for a job for the time being because there are no jobs available—say, a laid-off steelworker in a deeply depressed steel town—isn’t counted as unemployed because he or she has not been searching for a job during the previous four weeks. Individuals who want to work but have told government researchers that they aren’t currently searching because they see little prospect of finding a job given the state of the job market are called discouraged workers. Because it does not count discouraged workers, the measured unemployment rate may understate the percentage of people who want to work but are unable to find jobs.

Discouraged workers are part of a larger group—marginally attached workers. These are people who say they would like to have a job and have looked for work in the recent past but are not currently looking for work. They, too, are not included when calculating the unemployment rate.

Finally, another category of workers who are frustrated in their ability to find work but aren’t counted as unemployed are the underemployed: workers who would like to find full-time jobs but are currently working part time “for economic reasons”—that is, they can’t find a full-time job. Again, they aren’t counted in the unemployment rate.

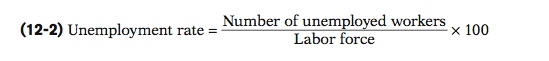

The Bureau of Labor Statistics is the federal agency that calculates the official unemployment rate. It also calculates broader “measures of labor underutilization” that include the three categories of frustrated workers. Figure 12-2 shows what happens to the measured unemployment rate once discouraged workers, other marginally attached workers, and the underemployed are counted. The broadest measure of unemployment and underemployment, known as U-6, is the sum of these three measures plus the unemployed. It is substantially higher than the rate usually quoted by the news media. But U-6 and the unemployment rate move very much in parallel, so changes in the unemployment rate remain a good guide to what’s happening in the overall labor market, including frustrated workers.

FIGURE 12-2 Alternative Measures of Unemployment, 1994–2011

Finally, it’s important to realize that the unemployment rate varies greatly among demographic groups. Other things equal, jobs are generally easier to find for more experienced workers and for workers during their “prime” working years, from ages 25 to 54. For younger workers, as well as workers nearing retirement age, jobs are typically harder to find, other things equal.

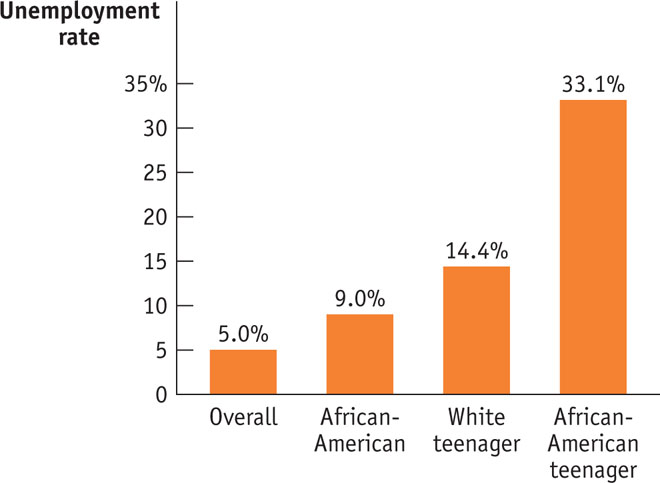

Figure 12-3 shows unemployment rates for different groups in December 2007, when the overall unemployment rate of 5.0% was low by historical standards. As you can see, at this time the unemployment rate for African-American workers was much higher than the national average; the unemployment rate for White teenagers (ages 16–19) was almost three times the national average; and the unemployment rate for African-American teenagers, at 33.1%, was over six times the national average. (Bear in mind that a teenager isn’t considered unemployed, even if he or she isn’t working, unless that teenager is looking for work but can’t find it.) So even at a time when the overall unemployment rate was relatively low, jobs were hard to find for some groups.

FIGURE 12-3 Unemployment Rates of Different Groups, 2007

So you should interpret the unemployment rate as an indicator of overall labor market conditions, not as an exact, literal measure of the percentage of people unable to find jobs. The unemployment rate is, however, a very good indicator: its ups and downs closely reflect economic changes that have a significant impact on people’s lives. Let’s turn now to the causes of these fluctuations.

Growth and Unemployment

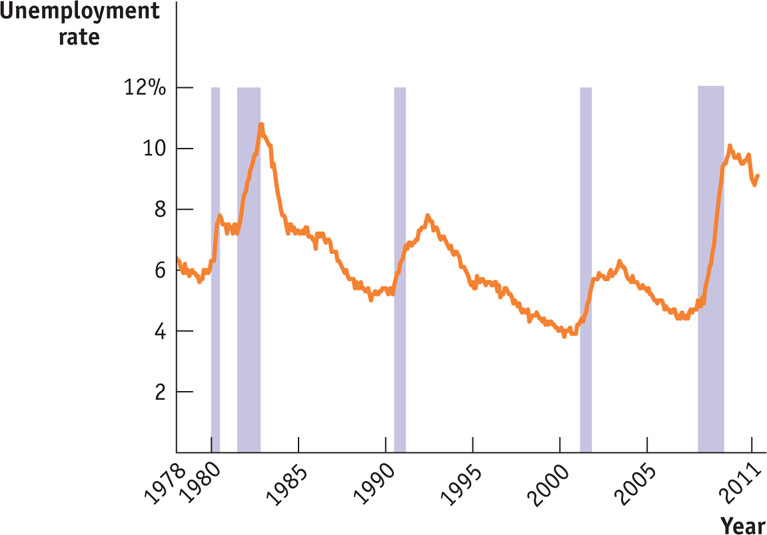

Compared to Figure 12-1, Figure 12-4 shows the U.S. unemployment rate over a somewhat shorter period, the 33 years from 1978 to 2011. The shaded bars represent periods of recession. As you can see, during every recession, without exception, the unemployment rate rose. The severe recession of 2007–2009, like the earlier one of 1981–1982, led to a huge rise in unemployment.

Correspondingly, during periods of economic expansion the unemployment rate usually falls. The long economic expansion of the 1990s eventually brought the unemployment rate below 4%, and the expansion of the mid-2000s brought the rate down to 4.7%. However, it’s important to recognize that economic expansions aren’t always periods of falling unemployment. Look at the periods immediately following the recessions of 1990–1991 and 2001 in Figure 12-4. In each case the unemployment rate continued to rise for more than a year after the recession was officially over. The explanation in both cases is that although the economy was growing, it was not growing fast enough to reduce the unemployment rate.

FIGURE 12-4 Unemployment and Recessions, 1978–2011

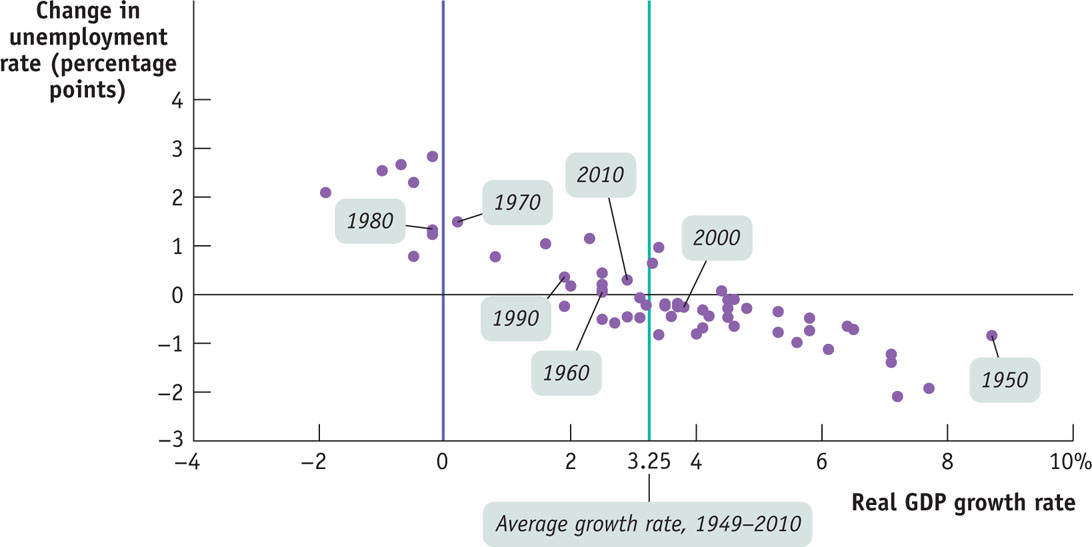

Figure 12-5 is a scatter diagram showing U.S. data for the period from 1949 to 2010. The horizontal axis measures the annual rate of growth in real GDP—the percent by which each year’s real GDP changed compared to the previous year’s real GDP. (Notice that there were nine years in which growth was negative—that is, real GDP shrank.) The vertical axis measures the change in the unemployment rate over the previous year in percentage points. Each dot represents the observed growth rate of real GDP and change in the unemployment rate for a given year. For example, in 2000 the average unemployment rate fell to 4.0% from 4.2% in 1999; this is shown as a value of −0.2 along the vertical axis for the year 2000. Over the same period, real GDP grew by 3.7%; this is the value shown along the horizontal axis for the year 2000.

FIGURE 12-5 Growth and Changes in Unemployment, 1949–2010

The downward trend of the scatter diagram in Figure 12-5 shows that there is a generally strong negative relationship between growth in the economy and the rate of unemployment. Years of high growth in real GDP were also years in which the unemployment rate fell, and years of low or negative growth in real GDP were years in which the unemployment rate rose.

The green vertical line in Figure 12-5 at the value of 3.25% indicates the average growth rate of real GDP over the period from 1949 to 2010. Points lying to the right of the vertical line are years of above-average growth. In these years, the value on the vertical axis is usually negative, meaning that the unemployment rate fell. That is, years of above-average growth were usually years in which the unemployment rate was falling. Conversely, points lying to the left of the green vertical line were years of below-average growth. In these years, the value on the vertical axis is usually positive, meaning that the unemployment rate rose. That is, years of below-average growth were usually years in which the unemployment rate was rising.

A jobless recovery is a period in which the real GDP growth rate is positive but the unemployment rate is still rising.

A period in which real GDP is growing at a below-average rate and unemployment is rising is called a jobless recovery or a “growth recession.” Since 1990, there have been three recessions, all of which have been followed by jobless recoveries. But true recessions, periods when real GDP falls, are especially painful for workers. As illustrated by the points to the left of the purple vertical line in Figure 12-5 (representing years in which the real GDP growth rate is negative), falling real GDP is always associated with a rising rate of unemployment, causing a great deal of hardship to families.

Failure to Launch

In March 2010, when the U.S. job situation was near its worst, the Harvard Law Record published a brief note titled “Unemployed law student will work for $160K plus benefits.” In a self-mocking tone, the author admitted to having graduated from Harvard Law School the previous year but not landing a job offer. “What mark on our résumé is so bad that it outweighs the crimson H?” the note asked.

The answer, of course, is that it wasn’t about the résumé—it was about the economy. Times of high unemployment are especially hard on new graduates, who often find it hard to get any kind of full-time job.

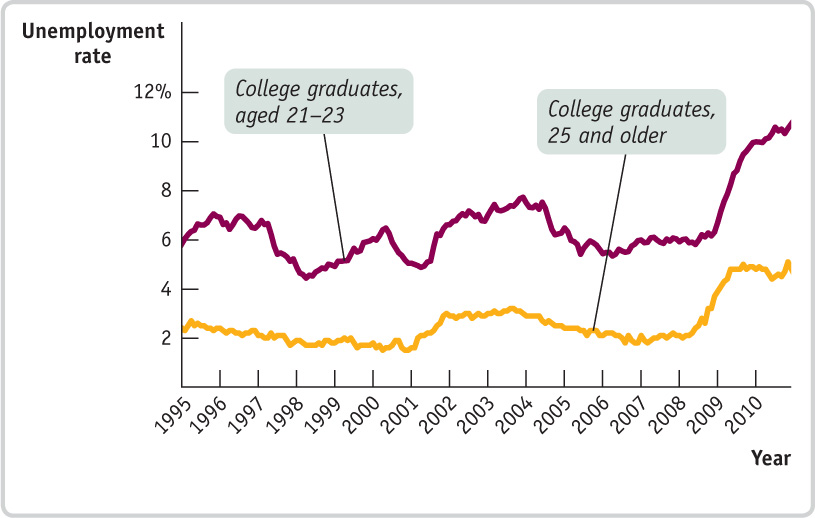

How bad was it in March 2010, around the time that note was written? Researchers at the San Francisco Fed analyzed the employment experience of college graduates, ages 21–23, and their findings are in Figure 12-6.

FIGURE 12-6 Unemployment Rate for Recent College Graduates, 1995–2010

Although the overall unemployment rate for college graduates 25 and older, even at its peak, was only about 5 percent, unemployment among recent graduates aged 21–23 peaked in 2010 at 10.7 percent. And many of those who were employed had been able to get only part-time jobs. In December 2007, at the beginning of the 2007–2009 recession, 83 percent of college graduates under the age of 24 who weren’t still in school were employed full time. By December 2009, that number was down to just 72 percent. Quite simply, many college graduates were having a hard time getting their working lives started.

A year later, the situation was starting to improve, but slowly: in December 2010, 74 percent of recent graduates had full-time jobs. The U.S. labor market had a long way to go before being able to offer college graduates—and young people in general—the kinds of opportunities they deserved.

Quick Review

- The labor force, equal to employment plus unemployment, does not include discouraged workers. Nor do labor statistics contain data on underemployment. The labor force participation rate is the percentage of the population age 16 and over in the labor force.

- The unemployment rate is an indicator of the state of the labor market, not an exact measure of the percentage of workers who can’t find jobs. It can overstate the true level of unemployment because workers often spend time searching for a job even when jobs are plentiful. But it can also understate the true level of unemployment because it excludes discouraged workers, marginally attached workers, and underemployed workers.

- There is a strong negative relationship between growth in real GDP and changes in the unemployment rate. When growth is above average, the unemployment rate generally falls. When growth is below average, the unemployment rate generally rises—a period called a jobless recovery that typically follows a deep recession.

Check Your Understanding 12-1

Question

Suppose that the advent of employment websites enables job-seekers to find suitable jobs more quickly. What effect will this have on the unemployment rate?

A. B. C. The advent of websites that enable jobseekers to find jobs more quickly will reduce the unemployment rate over time. However, websites that induce discouraged workers to begin actively looking for work again will lead to an increase in the unemployment rate over time.Question

In the following case is the worker counted as unemployed?

Rosa, an older worker who has been laid off and who gave up looking for work months ago.A. B. Rosa is not counted as unemployed because she is not actively looking for work, but she is counted in broader measures of labor underutilization as a discouraged worker.Question

In the following case is the worker counted as unemployed?

Anthony, a schoolteacher who is not working during his threemonth summer break.A. B. Anthony is not counted as unemployed; he is considered employed because he has a job.Question

In the following case is the worker counted as unemployed?

Grace, an investment banker who has been laid off and is currently searching for another position.A. B. Grace is unemployed; she is not working and is actively looking for work.Question

In the following case is the worker counted as unemployed?

Sergio, a classically trained musician who can only find work playing for local parties.A. B. Sergio is not unemployed, but underemployed; he is working parttime for economic reasons. He is counted in broader measures of labor underutilization.Question

In the following case is the worker counted as unemployed?

Natasha, a graduate student who went back to school because jobs were scarce.A. B. Natasha is not unemployed, but marginally attached. She is counted in broader measures of labor underutilization.

Question

Is the following scenario consistent with the observed relationship between growth in real GDP and changes in the unemployment rate?

A rise in the unemployment rate accompanies a fall in real GDP.A. B. This is consistent with the relationship between aboveaverage or below-average growth in real GDP and changes in the unemployment rate: during years of above-average growth, the unemployment rate falls, and during years of below-average growth, the unemployment rate rises.Question

Is the following scenario consistent with the observed relationship between growth in real GDP and changes in the unemployment rate?

An exceptionally strong business recovery is associated with a greater percentage of the labor force being employed.A. B. This is consistent with the relationship between above-average or below-average growth in real GDP and changes in the unemployment rate: during years of above-average growth, the unemployment rate falls, and during years of below-average growth, the unemployment rate rises.Question

Is the following scenario consistent with the observed relationship between growth in real GDP and changes in the unemployment rate?

Negative real GDP growth is associated with a fall in the unemployment rate.A. B. This is not consistent: it implies that a recession is associated with a fall in the unemployment rate.

Solutions appear at back of book.