Business Cases

Is What’s Good for America Good for General Motors?

On June 1, 2009, General Motors filed for bankruptcy. It was a sad comedown for a company that had once been the very symbol of American economic success—so much so that in 1953 the company’s CEO declared that the company’s interests and those of the nation were identical: “For years I thought that what was good for the country was good for General Motors, and vice versa.”

The 2009 bankruptcy didn’t mean that GM shut down; the company was able to continue operating thanks to almost $50 billion in federal aid. In return for that aid, the government received stock in the restructured company. The government’s intention was to sell off that stock later, once the company was profitable again.

But why did government officials believe that GM had a reasonable prospect of returning to profitability? Their case was based on an observation and a prediction.

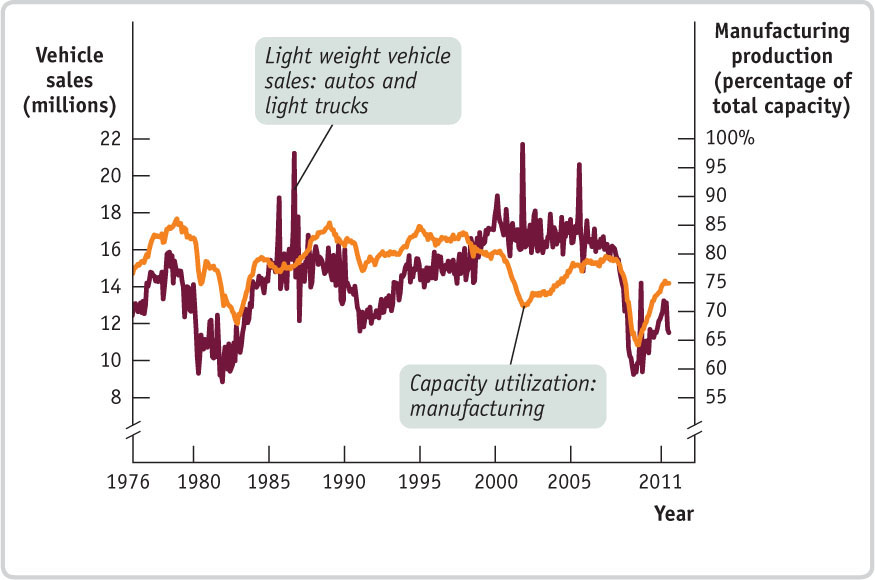

The observation was that GM’s troubles weren’t unique. To be sure, the company had been badly run and needed both to make better cars and to reduce its costs. But all U.S. automakers were in trouble: overall car sales had slumped and, beyond that, overall manufacturing production had slumped. The association of weak auto sales with a general manufacturing slump fit the historical pattern. The accompanying figure shows U.S. auto sales and total U.S. manufacturing production as a percentage of capacity; the two series have often, although not always, moved together.

The prediction was that both manufacturing production and auto sales would soon rebound, improving GM’s bottom line. And this indeed proved to be the case: as the economy bounced back, so did General Motors, which returned to profitability in 2010. By late 2010, the government was able to start selling off its stock, reducing its share in the company from about 60% to about 30%. As of December 2012, the government had not completely sold its 30% stake, but General Motors remained profitable.

So far, at least, the old line still applies: what is good for America is indeed good for General Motors, and vice versa.

U.S. Auto Sales and Total Manufacturing Production, 1976–2011

- Why do overall manufacturing production and auto sales tend to move together?

- Why was it reasonable in June 2009 to predict that auto sales would improve in the near future?

- Why was the Obama administration especially lucky that it stepped in to rescue GM in June 2009 rather than, say, six months earlier?

Getting a Jump on GDP

GDP matters. Investors and business leaders are always anxious to get the latest numbers. When the Bureau of Economic Analysis releases its first estimate of each quarter’s GDP, normally on the 27th or 28th day of the month after the quarter ends, it’s invariably a big news story.

In fact, many companies and other players in the economy are so eager to know what’s happening to GDP that they don’t want to wait for the official estimate. So a number of organizations produce numbers that can be used to predict what the official GDP number will say. Let’s talk about two of those organizations, the economic consulting firm Macroeconomic Advisers and the nonprofit Institute of Supply Management.

Macroeconomic Advisers takes a direct approach: it produces its own estimates of GDP based on raw data from the U.S. government. But whereas the Bureau of Economic Analysis estimates GDP only on a quarterly basis, Macroeconomic Advisers produces monthly estimates. This means that clients can, for example, look at the estimates for January and February and make a pretty good guess at what first-quarter GDP, which also includes March, will turn out to be. The monthly estimates are derived by looking at a number of monthly measures that track purchases, such as car and truck sales, new housing construction, and exports.

The Institute for Supply Management (ISM) takes a very different approach. It relies on monthly surveys of purchasing managers—that is, executives in charge of buying supplies—who are basically asked whether their companies are increasing or reducing production. (We say “basically” because the ISM asks a longer list of questions.) Responses to the surveys are released in the form of indexes showing the percentage of companies that are expanding. Obviously, these indexes don’t directly tell you what is happening to GDP. But historically, the ISM indexes have been strongly correlated with the rate of growth of GDP, and this historical relationship can be used to translate ISM data into “early warning” GDP estimates.

So if you just can’t wait for those quarterly GDP numbers, you’re not alone. The private sector has responded to demand, and you can get your data fix every month.

- Why do businesses care about GDP to such an extent that they want early estimates?

- How do the methods of Macroeconomic Advisers and the Institute of Supply Management fit into the three different ways to calculate GDP?

- If private firms are producing GDP estimates, why do we need the Bureau of Economic Analysis?

A Monster Slump

The 1990s were famously an era of business hype, a decade when numerous Internet-based companies were created, then sold their stock at incredibly high prices, and, in the end, went bust. Some of the dot-coms, however, turned out to have workable business models and have endured. Among them is Monster.com, a job-search company that, along with its competitors, has helped replace traditional help-wanted ads in newspapers with online listings.

Monster Worldwide (the company’s current name) and its competitors sell services to both employers seeking workers and workers seeking jobs. The employers place job listings, to which workers can respond; in addition to responding to these listings, job-seekers can pay for premium services such as résumé-writing and priority listing of their résumés.

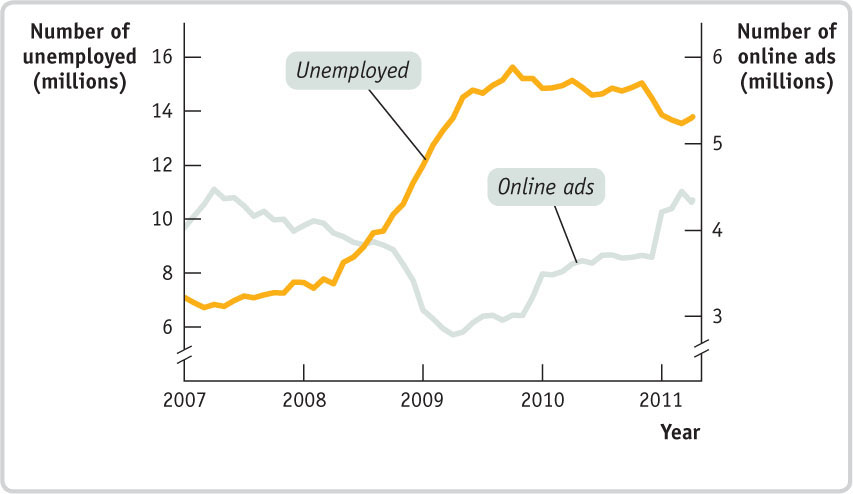

The growing importance of online job listings was brought home in 2007 when The Conference Board, a business group that has long tracked the economy by producing an index of help-wanted ads, added an index of online help-wanted ads. As the accompanying figure shows, a plunge in online help-wanted ads heralded the surge in unemployment in 2008–2009; when online ads began to recover, unemployment stabilized and began a slow decline.

In the late 1990s, when the U.S. economy was experiencing unusually low unemployment, some economists suggested that Monster Worldwide and other Internet job services might be partly responsible, by making it easier for workers to get new jobs without a prolonged intervening period of unemployment. The evidence for this effect is, however, inconclusive.

You might have thought that the 2007–2009 recession, in which many laid-off workers were desperately seeking new jobs, would have been good for Monster. And the company did, in fact, receive a lot more business from workers wanting to post their résumés. But the company makes much more money from employer job listings, and these were sharply lower during the slump, hurting Monster’s bottom line.

By late 2010, the economy seemed to be on the road to recovery, but online job listings were losing ground to Twitter and social networks. In fact, by the end of 2012, Monster had lost 90% of its value, primarily due to the rise of LinkedIn and other professional and social networking sites.

A Plunge in Online Help-Wanted Ads Heralds a Surge in Unemployment, 2008–2009

- Use the flows shown in Figure 12-7 to explain the potential role of online job listings in the economy.

- In light of our discussion of the determinants of the unemployment rate, how could improved matching of job-seekers and employers through online job listings help?

- What does the fact that Monster did badly during the 2008–2009 surge in unemployment suggest about the nature of that surge?