Comparing Economies Across Time and Space

Before we analyze the sources of long-run economic growth, it’s useful to have a sense of just how much the U.S. economy has grown over time and how large the gaps are between wealthy countries like the United States and countries that have yet to achieve comparable growth. So let’s take a look at the numbers.

Real GDP per Capita

The key statistic used to track economic growth is real GDP per capita—real GDP divided by the population size. We focus on GDP because, as we learned in Chapter 11, GDP measures the total value of an economy’s production of final goods and services as well as the income earned in that economy in a given year. We use real GDP because we want to separate changes in the quantity of goods and services from the effects of a rising price level. We focus on real GDP per capita because we want to isolate the effect of changes in the population. For example, other things equal, an increase in the population lowers the standard of living for the average person—there are now more people to share a given amount of real GDP. An increase in real GDP that only matches an increase in population leaves the average standard of living unchanged.

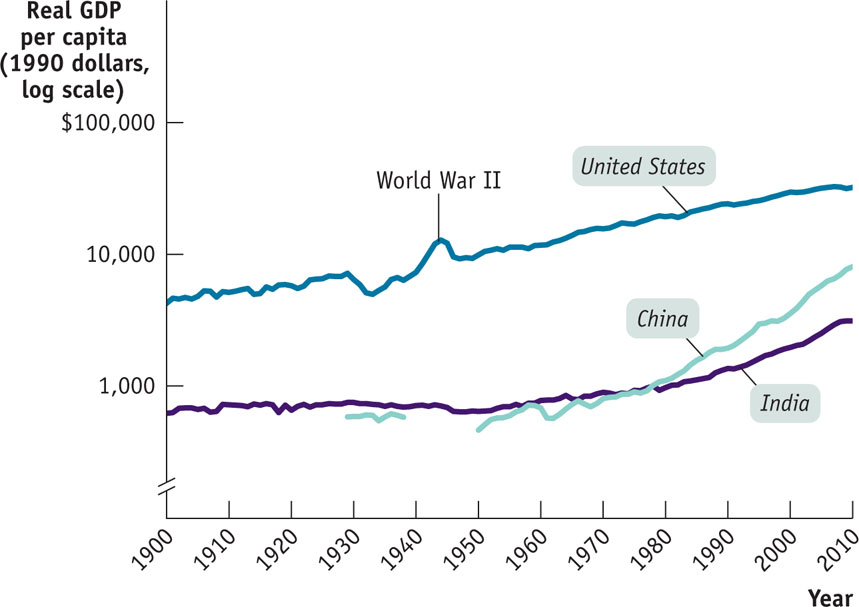

Although we also learned in Chapter 11 that growth in real GDP per capita should not be a policy goal in and of itself, it does serve as a very useful summary measure of a country’s economic progress over time. Figure 13-1 shows real GDP per capita for the United States, India, and China, measured in 1990 dollars, from 1900 to 2010. (We’ll talk about India and China in a moment.) The vertical axis is drawn on a logarithmic scale so that equal percent changes in real GDP per capita across countries are the same size in the graph.

FIGURE 13-1 Economic Growth in the United States, India, and China over the Past Century

To give a sense of how much the U.S. economy grew during the last century, Table 13-1 shows real GDP per capita at selected years, expressed two ways: as a percentage of the 1900 level and as a percentage of the 2010 level. In 1920, the U.S. economy already produced 136% as much per person as it did in 1900. In 2010, it produced 758% as much per person as it did in 1900, a more than sevenfold increase. Alternatively, in 1900 the U.S. economy produced only 13% as much per person as it did in 2010.

TABLE 13-1 U.S. Real GDP per Capita

| Year | Percentage of 1900 real GDP per capita | Percentage of 2010 real GDP per capita |

|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 100% | 13% |

| 1920 | 136 | 18 |

| 1940 | 171 | 23 |

| 1980 | 454 | 60 |

| 2000 | 696 | 92 |

| 2010 | 758 | 100 |

The income of the typical family normally grows more or less in proportion to per capita income. For example, a 1% increase in real GDP per capita corresponds, roughly, to a 1% increase in the income of the median or typical family—a family at the center of the income distribution. In 2010, the median American household had an income of about $50,000. Since Table 13-1 tells us that real GDP per capita in 1900 was only 13% of its 2010 level, a typical family in 1900 probably had a purchasing power only 13% as large as the purchasing power of a typical family in 2010. That’s around $6,100 in today’s dollars, representing a standard of living that we would now consider severe poverty. Today’s typical American family, if transported back to the United States of 1900, would feel quite a lot of deprivation.

Yet many people in the world have a standard of living equal to or lower than that of the United States at the beginning of the last century. That’s the message about China and India in Figure 13-1: despite dramatic economic growth in China over the last three decades and the less dramatic acceleration of economic growth in India, China has only recently exceeded the standard of living that the United States enjoyed in the early twentieth century, while India is still poorer than the United States was at that time. And much of the world today is poorer than China or India.

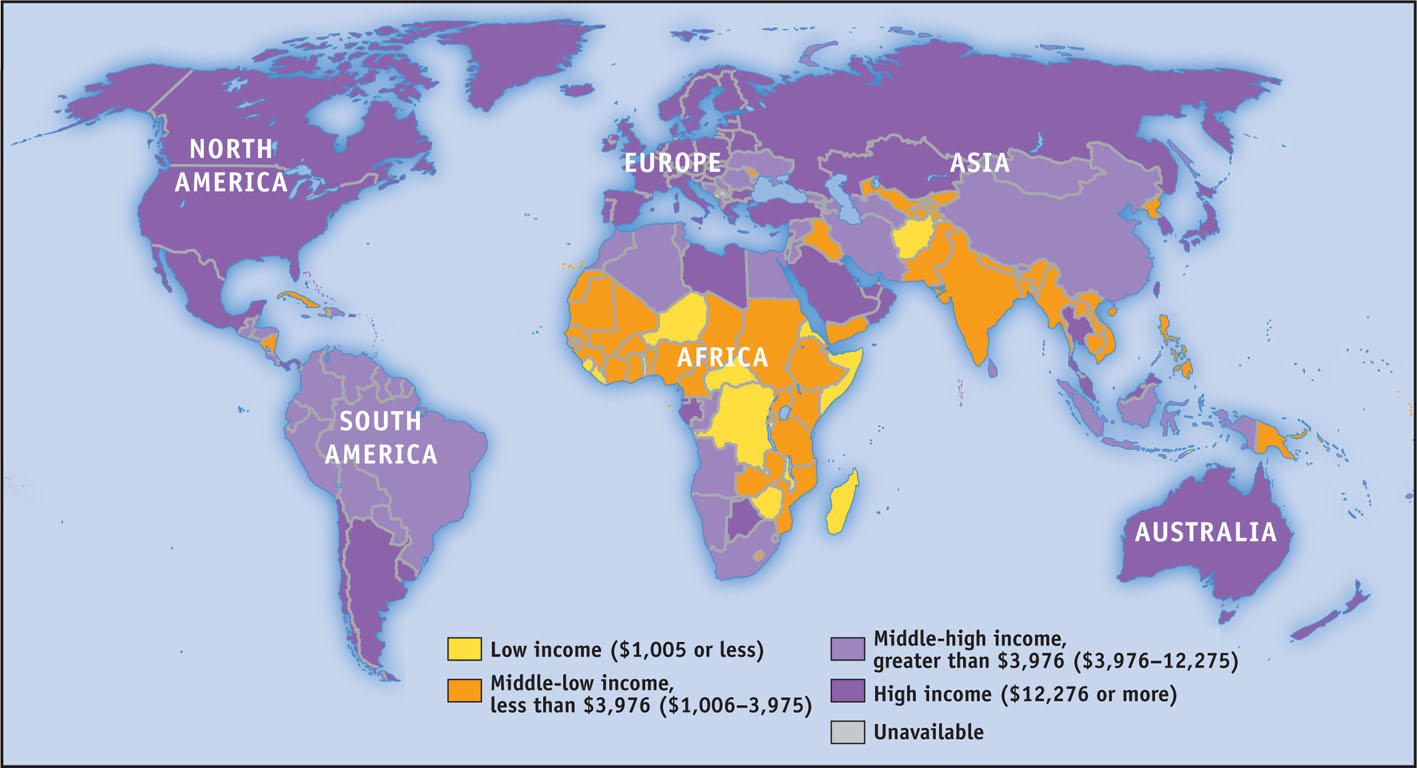

You can get a sense of how poor much of the world remains by looking at Figure 13-2, a map of the world in which countries are classified according to their 2010 levels of GDP per capita, in U.S. dollars. As you can see, large parts of the world have very low incomes. Generally speaking, the countries of Europe and North America, as well as a few in the Pacific, have high incomes. The rest of the world, containing most of its population, is dominated by countries with GDP less than $3,976 per capita—and often much less. In fact, today about 50% of the world’s people live in countries with a lower standard of living than the United States had a century ago.

FIGURE 13-2 Incomes Around the World, 2010

Change in Levels Versus Rate of Change

When studying economic growth, it’s vitally important to understand the difference between a change in level and a rate of change. When we say that real GDP “grew,” we mean that the level of real GDP increased. For example, we might say that U.S. real GDP grew during 2010 by $385 billion.

If we knew the level of U.S. real GDP in 2009, we could also represent the amount of 2010 growth in terms of a rate of change. For example, if U.S. real GDP in 2009 was $12,703 billion, then U.S. real GDP in 2010 was $12,703 billion + $385 billion = $13,088 billion. We could calculate the rate of change, or the growth rate, of U.S. real GDP during 2010 as: (($13,088 billion − $12,703 billion)/$12,703 billion) × 100 = ($385 billion/$12,703 billion) × 100 = 3.03%. Statements about economic growth over a period of years almost always refer to changes in the growth rate.

When talking about growth or growth rates, economists often use phrases that appear to mix the two concepts and so can be confusing. For example, when we say that “U.S. growth fell during the 1970s,” we are really saying that the U.S. growth rate of real GDP was lower in the 1970s in comparison to the 1960s. When we say that “growth accelerated during the early 1990s,” we are saying that the growth rate increased year after year in the early 1990s—for example, going from 3% to 3.5% to 4%.

Growth Rates

How did the United States manage to produce over seven times as much per person in 2010 than in 1900? A little bit at a time. Long-run economic growth is normally a gradual process in which real GDP per capita grows at most a few percent per year. From 1900 to 2010, real GDP per capita in the United States increased an average of 1.9% each year.

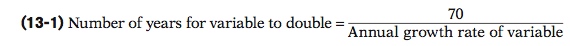

According to the Rule of 70, the time it takes a variable that grows gradually over time to double is approximately 70 divided by that variable’s annual growth rate.

To have a sense of the relationship between the annual growth rate of real GDP per capita and the long-run change in real GDP per capita, it’s helpful to keep in mind the Rule of 70, a mathematical formula that tells us how long it takes real GDP per capita, or any other variable that grows gradually over time, to double. The approximate answer is:

(Note that the Rule of 70 can only be applied to a positive growth rate.) So if real GDP per capita grows at 1% per year, it will take 70 years to double. If it grows at 2% per year, it will take only 35 years to double. In fact, U.S. real GDP per capita rose on average 1.9% per year over the last century. Applying the Rule of 70 to this information implies that it should have taken 37 years for real GDP per capita to double; it would have taken 111 years—three periods of 37 years each—for U.S. real GDP per capita to double three times. That is, the Rule of 70 implies that over the course of 111 years, U.S. real GDP per capita should have increased by a factor of 2 × 2 × 2 = 8. And this does turn out to be a pretty good approximation of reality. Between 1899 and 2010—a period of 111 years—real GDP per capita rose just about eightfold.

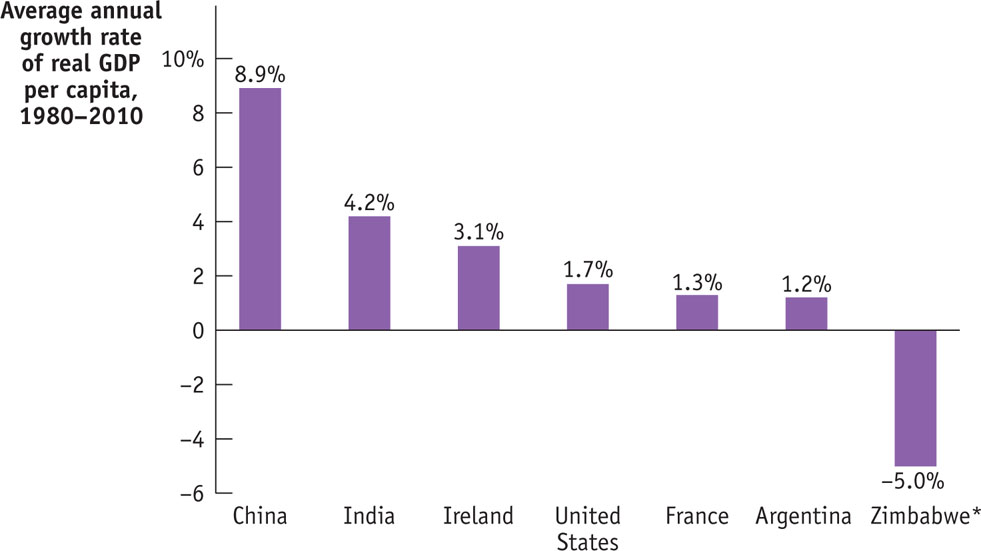

Figure 13-3 shows the average annual rate of growth of real GDP per capita for selected countries from 1980 to 2010. Some countries were notable success stories: for example, China, though still quite a poor country, has made spectacular progress. India, although not matching China’s performance, has also achieved impressive growth, as discussed in the following Economics in Action.

FIGURE 13-3 Comparing Recent Growth Rates

*Data for Zimbabwe is average annual growth rate 2000–2010 due to data limitations.

Some countries, though, have had very disappointing growth. Argentina was once considered a wealthy nation. In the early years of the twentieth century, it was in the same league as the United States and Canada. But since then it has lagged far behind more dynamic economies. And still others, like Zimbabwe, have slid backward.

What explains these differences in growth rates? To answer that question, we need to examine the sources of long-run economic growth.

India Takes Off

India achieved independence from Great Britain in 1947, becoming the world’s most populous democracy—a status it has maintained to this day. For more than three decades after independence, however, this happy political story was partly overshadowed by economic disappointment. Despite ambitious economic development plans, India’s performance was consistently sluggish. In 1980, India’s real GDP per capita was only about 50% higher than it had been in 1947; the gap between Indian living standards and those in wealthy countries like the United States had been growing rather than shrinking.

Since then, however, India has done much better. As Figure 13-3 shows, real GDP per capita has grown at an average rate of 4.2% a year, more than tripling between 1980 and 2010. India now has a large and rapidly growing middle class. And yes, the well-fed children of that middle class are much taller than their parents.

What went right in India after 1980? Many economists point to policy reforms. For decades after independence, India had a tightly controlled, highly regulated economy. Today, things are very different: a series of reforms opened the economy to international trade and freed up domestic competition. Some economists, however, argue that this can’t be the main story because the big policy reforms weren’t adopted until 1991, yet growth accelerated around 1980.

Regardless of the explanation, India’s economic rise has transformed it into a major new economic power—and allowed hundreds of millions of people to have a much better life, better than their grandparents could have dreamed.

The big question now is whether this growth can continue. Skeptics argue that there are important bottlenecks in the Indian economy that may constrain future growth. They point in particular to the still low education level of much of India’s population and inadequate infrastructure—that is, the poor quality and limited capacity of the country’s roads, railroads, power supplies, and so on. But India’s economy has defied the skeptics for several decades and the hope is that it can continue doing so.

Quick Review

- Economic growth is measured using real GDP per capita.

- In the United States, real GDP per capita increased over sevenfold since 1900, resulting in a large increase in living standards.

- Many countries have real GDP per capita much lower than that of the United States. More than half of the world’s population has living standards worse than those existing in the United States in the early 1900s.

- The long-term rise in real GDP per capita is the result of gradual growth. The Rule of 70 tells us how many years at a given annual rate of growth it takes to double real GDP per capita.

- Growth rates of real GDP per capita differ substantially among nations.

Check Your Understanding 13-1

Question

Which of the following is a correct statement about measuring economic progress?

A. B. C. D. Economic progress raises the living standards of the average resident of a country. An increase in overall real GDP does not accurately reflect an increase in an average resident’s living standard because it does not account for growth in the number of residents. If, for example, real GDP rises by 10% but population grows by 20%, the living standard of the average resident falls: after the change, the average resident has only (110/120) x 100 = 91.6% as much real income as before the change. Similarly, an increase in nominal GDP per capita does not accurately reflect an increase in living standards because it does not account for any change in prices. For example, a 5% increase in nominal GDP per capita generated by a 5% increase in prices implies that there has been no change in living standards. Real GDP per capita is the only measure that accounts for both changes in the population and changes in prices.Question

India’s average annual growth rate of real GDP per capita from 1980-2007 in India was 4.1% and in the United States was 2.0%. Apply the Rule of 70 to this data to determine how long it will take each country to double its real GDP per capita. Would India’s real GDP per capita exceed that of the United States in the future if growth rates remain the same?

A. B. Using the Rule of 70, the amount of time it will take for India is 17.1 years; the United States is 35 years. If India continues to have a higher growth rate of real GDP per capita than the United States, then India’s real GDP per capita will eventually surpass that of the United States.Question

Although China and India currently have growth rates much higher than the U.S. growth rate, the typical Chinese or Indian household is far poorer than the typical American household. Which of the following statements explains why that is?

A. B. C. The United States began growing rapidly over a century ago, but China and India have begun growing rapidly only recently. As a result, the living standard of the typical Chinese or Indian household has not yet caught up with that of the typical American household.

Solutions appear at back of book.