Business Cases

Big Box Boom

After 20 years of being sluggish, U.S. productivity growth accelerated sharply in the late 1990s; that is, productivity began to grow at a much faster rate than previously. What caused that acceleration? Was it the rise of the Internet?

Not according to analysts at McKinsey and Co., the famous business consulting firm. They found that a major source of productivity improvement after 1995 was a surge in output per worker in retailing—stores were selling much more merchandise per worker.

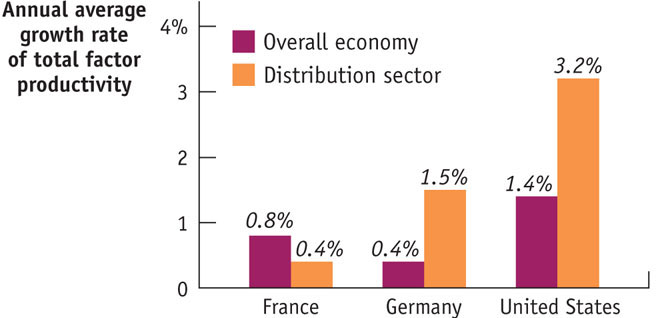

Other analysts agree. The accompanying figure shows the result of an analysis of total factor productivity growth in France, Germany, and the United States between 1995 and 2004, the decade of the U.S. productivity surge. As you can see, the United States did considerably better than either European nation. The key to the surge was very fast growth in the productivity of the distribution sector, that is, in wholesale and retail trade.

Why did productivity surge in retailing in the United States? “The reason can be explained in just two syllables: Walmart,” wrote McKinsey.

Walmart is famed in the business world for its successful focus on the unglamorous but crucial area of logistics: getting stuff where it was needed, when it was needed. For example, it was one of the first companies to use computers to track inventory, to use bar-code scanners, to establish direct electronic links with suppliers, and so on. These practices gave it a huge advantage over competitors, leading to high profits and rapid expansion. Other firms, observing Walmart’s success, have emulated its business practices, spreading productivity gains through the economy as a whole.

There are two lessons from the “Walmart effect,” as McKinsey calls it. One is that how you apply a technology makes all the difference: everyone in the retail business knew about computers, but Walmart figured out what to do with them. The other is that a lot of economic growth comes from everyday improvements rather than flashy new technologies.

- In Chapter 13 we described several sources of productivity growth. Which of these sources corresponds to the “Walmart effect”?

- How does our description of Walmart’s role tie in with the New Growth Theory?

- How does the Walmart story relate to the “information technology paradox”?

United in Pain

The airline industry is notoriously cyclical. That is, instead of making profits all through the business cycle, it tends to plunge into losses during recessions, only regaining profitability sometime after recovery begins. Mainly this is because airlines have large fixed costs that remain high even if ticket sales slump. The cost of operating a flight from one city to another is pretty much the same whether the flight is fully booked or two-thirds empty, so when business slumps for whatever reason, even highly profitable routes quickly become money-losers. It’s true that airlines can to some extent adapt to a decline in business by switching to smaller planes, consolidating flights, and so on, but this process takes time and still tends to leave costs per passenger higher than before.

But some recessions are worse for airlines than for other businesses, because operating costs rise even as demand falls. This was very much the case in early 2008. In the spring of that year, the so-called Great Recession of 2007–2009 was still in its early stages, with unemployment just starting to rise. Yet airlines were already, as an article in the Los Angeles Times put it, in a “sea of red ink.” The article highlighted the case of United Airlines, which had suddenly plunged into large losses and was planning large layoffs.

Why was United in so much trouble? Business travel had started to slacken, but at that point leisure travel, such as flights to Disney World, was still holding up. What was hurting United and its sister airlines was the cost of fuel, which soared in late 2007 and early 2008.

Fuel prices fell back down in late 2008. But by that time United was suffering from a sharp drop in ticket sales. The airline finally returned to profitability in 2010, which was also the year it agreed to merge with Continental. In 2011, United Continental earned $840 million in profits, offsetting high fuel prices with increased revenue. But the news was far more bleak in 2012 when the airline, faced with operational and other problems, lost over $700 million.

- How did United’s problems in early 2008 relate to our analysis of the causes of recessions?

- Ben Bernanke had to make a choice between fighting two evils in early 2008. How would that choice affect United compared with, say, a company producing a service without expensive raw-material inputs, like health care?

- In early 2008, business travel was beginning to slacken, but leisure travel was still holding up. Given the situation the overall economy was in, what would you expect to happen to leisure travel as the economy moved further into recession?