Fiscal Policy and the Multiplier

An expansionary fiscal policy, like the 2009 U.S. stimulus, pushes the aggregate demand curve to the right. A contractionary fiscal policy, like Lyndon Johnson’s tax surcharge, pushes the aggregate demand curve to the left. For policy makers, however, knowing the direction of the shift isn’t enough: they need estimates of how much a given policy will shift the aggregate demand curve. To get these estimates, they use the concept of the multiplier.

Multiplier Effects of an Increase in Government Purchases of Goods and Services

Suppose that a government decides to spend $50 billion building bridges and roads. The government’s purchases of goods and services will directly increase total spending on final goods and services by $50 billion. But there will also be an indirect effect: the government’s purchases will start a chain reaction throughout the economy.

An autonomous change in aggregate spending is an initial change in the desired level of spending by firms, households, or government at a given level of real GDP. The multiplier is the ratio of the total change in real GDP caused by an autonomous change in aggregate spending to the size of that autonomous change.

The firms that produce the goods and services purchased by the government earn revenues that flow to households in the form of wages, profits, interest, and rent. This increase in disposable income leads to a rise in consumer spending. The rise in consumer spending, in turn, induces firms to increase output, leading to a further rise in disposable income, which leads to another round of consumer spending increases, and so on. In this case, the multiplier is the ratio of the total change in real GDP caused by the change in the government’s purchases of goods and services. More generally, real GDP can change with any autonomous change in aggregate spending, not just a change in consumer spending. An autonomous change in aggregate spending is the initial rise or fall in the desired level of spending by firms, households, or government at a given level of GDP. Formally, the multiplier is the ratio of the total change in real GDP caused by an autonomous change in aggregate spending to the size of that autonomous change.

The marginal propensity to consume, or MPC, is the increase in consumer spending when disposable income rises by $1.

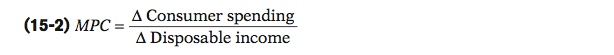

If we sum the effect from all these rounds of consumer spending increases, how large is the total effect on aggregate output? To answer this question, we need to introduce the concept of the marginal propensity to consume, or MPC: the increase in consumer spending when disposable income rises by $1. When consumer spending changes because of a rise or fall in disposable income, MPC is that change in consumer spending divided by the change in disposable income:

where the symbol Δ (delta) means “change in.” For example, if consumer spending goes up by $5 billion when disposable income goes up by $10 billion, MPC is $5 billion/$10 billion = 0.5.

Now, consider a simple case in which there are no taxes or international trade, so that any change in GDP accrues entirely to households. Also assume that the aggregate price level is fixed, so that any increase in nominal GDP is also a rise in real GDP, and assume that the interest rate is fixed. In this case, the multiplier is 1/(1 − MPC). So, if the marginal propensity to consume is 0.5, the multiplier is 1/(1 − 0.5) = 1/0.5 = 2. Given a multiplier of 2, a $50 billion increase in government purchases of goods and services would increase real GDP by $100 billion. Of that $100 billion, $50 billion is the initial effect from the increase in G, and the remaining $50 billion is the subsequent effect arising from the increase in consumer spending.

What happens if government purchases of goods and services are instead reduced? The math is exactly the same, except that there’s a minus sign in front: if government purchases of goods and services fall by $50 billion and the marginal propensity to consume is 0.5, real GDP falls by $100 billion.

Multiplier Effects of Changes in Government Transfers and Taxes

Expansionary or contractionary fiscal policy need not take the form of changes in government purchases of goods and services. Governments can also change transfer payments or taxes. In general, however, a change in government transfers or taxes shifts the aggregate demand curve by less than an equal-sized change in government purchases, resulting in a smaller effect on real GDP.

To see why, imagine that instead of spending $50 billion on building bridges, the government simply hands out $50 billion in the form of government transfers. In this case, there is no direct effect on aggregate demand, as there was with government purchases of goods and services. Real GDP goes up only because households spend some of that $50 billion—and they probably won’t spend it all.

Table 15-1 shows a hypothetical comparison of two expansionary fiscal policies assuming an MPC equal to 0.5 and a multiplier equal to 2: one in which the government directly purchases $50 billion in goods and services and one in which the government makes transfer payments instead, sending out $50 billion in checks to consumers. In each case there is a first-round effect on real GDP, either from purchases by the government or from purchases by the consumers who received the checks, followed by a series of additional rounds as rising real GDP raises disposable income.

TABLE 15-1 Hypothetical Effects of a Fiscal Policy with Multiplier of 2

| Effect on real GDP | $50 billion rise in government purchases of goods and services | $50 billion rise in government transfer payments |

|---|---|---|

| First round | $50 billion | $25 billion |

| Second round | $25 billion | $12.5 billion |

| Third round | $12.5 billion | $6.25 billion |

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ |

| Eventual effect | $100 billion | $50 billion |

However, the first-round effect of the transfer program is smaller; because we have assumed that the MPC is 0.5, only $25 billion of the $50 billion is spent, with the other $25 billion saved. And as a result, all the further rounds are smaller, too. In the end, the transfer payment increases real GDP by only $50 billion. In comparison, a $50 billion increase in government purchases produces a $100 billion increase in real GDP.

Overall, when expansionary fiscal policy takes the form of a rise in transfer payments, real GDP may rise by either more or less than the initial government outlay—that is, the multiplier may be either more or less than 1 depending upon the size of the MPC. In Table 15-1, with an MPC equal to 0.5, the multiplier is exactly 1: a $50 billion rise in transfer payments increases real GDP by $50 billion. If the MPC is less than 0.5, so that a smaller share of the initial transfer is spent, the multiplier on that transfer is less than 1. If a larger share of the initial transfer is spent, the multiplier is more than 1.

A tax cut has an effect similar to the effect of a transfer. It increases disposable income, leading to a series of increases in consumer spending. But the overall effect is smaller than that of an equal-sized increase in government purchases of goods and services: the autonomous increase in aggregate spending is smaller because households save part of the amount of the tax cut.

Lump-sum taxes are taxes that don’t depend on the taxpayer’s income.

We should also note that taxes introduce a further complication—they typically change the size of the multiplier. That’s because in the real world governments rarely impose lump-sum taxes, in which the amount of tax a household owes is independent of its income. With lump-sum taxes there is no change in the multiplier. Instead, the great majority of tax revenue is raised via taxes that are not lump-sum, and so tax revenue depends upon the level of real GDP.

In practice, economists often argue that the size of the multiplier determines who among the population should get tax cuts or increases in government transfers. For example, compare the effects of an increase in unemployment benefits with a cut in taxes on profits distributed to shareholders as dividends. Consumer surveys suggest that the average unemployed worker will spend a higher share of any increase in his or her disposable income than would the average recipient of dividend income. That is, people who are unemployed tend to have a higher MPC than people who own a lot of stocks because the latter tend to be wealthier and tend to save more of any increase in disposable income. If that’s true, a dollar spent on unemployment benefits increases aggregate demand more than a dollar’s worth of dividend tax cuts.

How Taxes Affect the Multiplier

The increase in government tax revenue when real GDP rises isn’t the result of a deliberate decision or action by the government. It’s a consequence of the way the tax laws are written, which causes most sources of government revenue to increase automatically when real GDP goes up. For example, income tax receipts increase when real GDP rises because the amount each individual owes in taxes depends positively on his or her income, and households’ taxable income rises when real GDP rises. Sales tax receipts increase when real GDP rises because people with more income spend more on goods and services. And corporate profit tax receipts increase when real GDP rises because profits increase when the economy expands.

The effect of these automatic increases in tax revenue is to reduce the size of the multiplier. Remember, the multiplier is the result of a chain reaction in which higher real GDP leads to higher disposable income, which leads to higher consumer spending, which leads to further increases in real GDP. The fact that the government siphons off some of any increase in real GDP means that at each stage of this process, the increase in consumer spending is smaller than it would be if taxes weren’t part of the picture. The result is to reduce the multiplier.

Many macroeconomists believe it’s a good thing that in real life taxes reduce the multiplier. In Chapter 14 we argued that most, though not all, recessions are the result of negative demand shocks. The same mechanism that causes tax revenue to increase when the economy expands causes it to decrease when the economy contracts. Since tax receipts decrease when real GDP falls, the effects of these negative demand shocks are smaller than they would be if there were no taxes. The decrease in tax revenue reduces the adverse effect of the initial fall in aggregate demand.

Automatic stabilizers are government spending and taxation rules that cause fiscal policy to be automatically expansionary when the economy contracts and automatically contractionary when the economy expands.

The automatic decrease in government tax revenue generated by a fall in real GDP—caused by a decrease in the amount of taxes households pay—acts like an automatic expansionary fiscal policy implemented in the face of a recession. Similarly, when the economy expands, the government finds itself automatically pursuing a contractionary fiscal policy—a tax increase. Government spending and taxation rules that cause fiscal policy to be automatically expansionary when the economy contracts and automatically contractionary when the economy expands, without requiring any deliberate action by policy makers, are called automatic stabilizers.

The rules that govern tax collection aren’t the only automatic stabilizers, although they are the most important ones. Some types of government transfers also play a stabilizing role. For example, more people receive unemployment insurance when the economy is depressed than when it is booming. The same is true of Medicaid and food stamps. So transfer payments tend to rise when the economy is contracting and fall when the economy is expanding. Like changes in tax revenue, these automatic changes in transfers tend to reduce the size of the multiplier because the total change in disposable income that results from a given rise or fall in real GDP is smaller.

As in the case of government tax revenue, many macroeconomists believe that it’s a good thing that government transfers reduce the multiplier. Expansionary and contractionary fiscal policies that are the result of automatic stabilizers are widely considered helpful to macroeconomic stabilization because they blunt the extremes of the business cycle.

Discretionary fiscal policy is fiscal policy that is the result of deliberate actions by policy makers rather than rules.

But what about fiscal policy that isn’t the result of automatic stabilizers? Discretionary fiscal policy is fiscal policy that is the direct result of deliberate actions by policy makers rather than automatic adjustment. For example, during a recession, the government may pass legislation that cuts taxes and increases government spending in order to stimulate the economy. In general, economists tend to support the use of discretionary fiscal policy only in special circumstances, such as an especially severe recession.

Multipliers and the Obama Stimulus

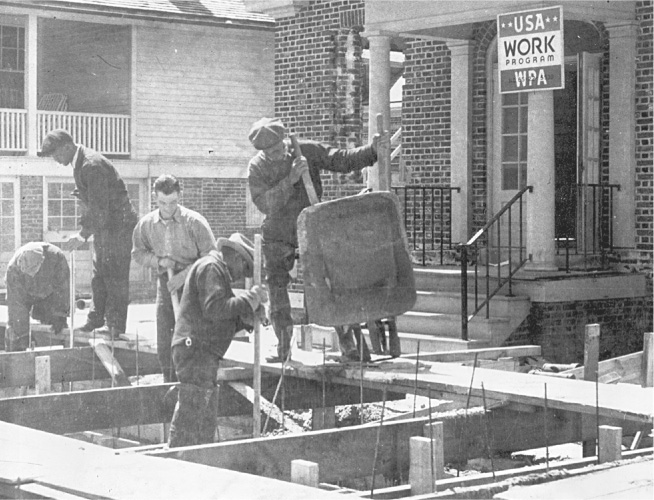

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, also known as the Obama stimulus, was the largest example of discretionary fiscal expansion in U.S. history. The total stimulus was $787 billion, although not all of that was spent at once: only about half, or roughly $400 billion, of the stimulus arrived in 2010, the year of peak impact. Still, even that was a lot—roughly 2.7% of GDP. But was that enough? From the beginning, there were doubts.

The first description of the planned stimulus and its expected effects came in early January 2009, from two of the incoming administration’s top economists—Christina Romer, who would head the Council of Economic Advisers, and Jared Bernstein, who would serve as the vice president’s chief economist. Romer and Bernstein were explicit about the assumed multipliers: based on models developed at the Federal Reserve and elsewhere, they assumed that government spending would have a multiplier of 1.57 and that tax cuts would have a multiplier of 0.99.

These assumptions yielded an overall multiplier for the stimulus of almost 1.4, implying that the stimulus would, at its peak in 2010, add about 3.7% to real GDP. It would also, they estimated, reduce unemployment by about 1.8 percentage points relative to what it would otherwise have been.

But here’s the problem: the slump the Obama stimulus was intended to fight was brought on by a major financial crisis—and such crises tend to produce very deep, prolonged slumps. Shortly before Romer and Bernstein released their analysis, another team of economists—Carmen Reinhart of the University of Maryland and Kenneth Rogoff of Harvard—circulated a paper titled “The Aftermath of Financial Crises,” based on historical episodes. Reinhart and Rogoff found that major crises are followed, on average, by a 7-percentage-point rise in the unemployment rate and that it takes years before unemployment falls to anything like normal levels.

Compared with the economy’s problems, then, the Obama stimulus was actually small: it cut only 1.8 points off the unemployment rate in 2010 and faded out rapidly thereafter. And given its small size relative to the problem, the failure of the stimulus to avert persistently high unemployment should not have come as a surprise.

Quick Review

- The multiplier is the ratio of the total change in real GDP caused by an autonomous change in aggregate spending to the size of that autonomous change. The multiplier is determined by the marginal propensity to consume (MPC).

- Changes in taxes and government transfers also move real GDP, but by less than equal-sized changes in government purchases.

- Taxes reduce the size of the multiplier unless they are lump-sum taxes.

- Taxes and some government transfers act as automatic stabilizers as tax revenue responds positively to changes in real GDP and some government transfers respond negatively to changes in real GDP. Many economists believe that it is a good thing that they reduce the size of the multiplier. In contrast, the use of discretionary fiscal policy is more controversial.

Check Your Understanding 15-2

Question

Assume there is either a $500 million increase in government purchases of goods and services or a $500 million increase in government transfers. Which of the following statements is correct in terms of the effect on real GDP?

A. B. C. D. A $500 million increase in government purchases of goods and services directly increases aggregate spending by $500 million, which then starts the multiplier in motion. It will increase real GDP by $500 million x 1/(1 - MPC). A $500 million increase in government transfers increases aggregate spending only to the extent that it leads to an increase in consumer spending. Consumer spending rises by MPC x $1 for every $1 increase in disposable income, where MPC is less than 1. So a $500 million increase in government transfers will cause a rise in real GDP only MPC times as much as a $500 million increase in government purchases of goods and services. It will increase real GDP by $500 million x MPC/(1- MPC).Question

True or False? A $500 million reduction in government transfers will generate a larger fall in real GDP than a $500 million reduction in government purchases of goods and services.

A. B. If government purchases of goods and services fall by $500 million, the initial fall in aggregate spending is $500 million. If there is a $500 million reduction in government transfers, the initial fall in aggregate spending is MPC x $500 million, which is less than $500 million.Question

The country of Boldovia has no unemployment insurance benefits and a tax system using only lump-sum taxes. The neighboring country of Moldovia has generous unemployment benefits and a tax system in which residents must pay a percentage of their income. Which country will experience greater variation in real GDP in response to demand shocks, positive and negative?

A. B. Boldovia will experience greater variation in its real GDP than Moldovia because Moldovia has automatic stabilizers while Boldovia does not. In Moldovia the effects of slumps will be lessened by unemployment insurance benefits which will support residents' incomes, while the effects of booms will be diminished because tax revenues will go up. In contrast, incomes will not be supported in Boldovia during slumps because there is no unemployment insurance. In addition, because Boldovia has lumpsum taxes, its booms will not be diminished by increases in tax revenue.

Solutions appear at back of book.