The Great Mistake of 1937

In 1937, policy makers at the Fed and in the Roosevelt administration decided that the Great Depression that began in 1929 was over. They believed that the economy no longer needed special support and began phasing out the policies they instituted in the early years of the decade. Spending was cut back, and monetary policy was tightened. The result was a serious relapse in 1938, often referred to at the time as the “second Great Depression.”

What caused this relapse? The answer, according to many economists, is that the setback was caused by the policy makers who pulled back too soon, tightening both fiscal and monetary policy, before the economy was on the path to full recovery. Everything else being equal, a tightening of monetary policy causes a drop in GDP. If the economy is starting to heat up and a boom is on its way, this tightening can be important to preventing inflation. But, if the economy is in a fragile state, a tightening of monetary policy can make things worse by decreasing GDP even further.

Using the liquidity preference model and the AD-AS model, show how in 1937 monetary policy made things worse for the economy by decreasing GDP in the short run and putting further downward pressure on prices in the short and long run.

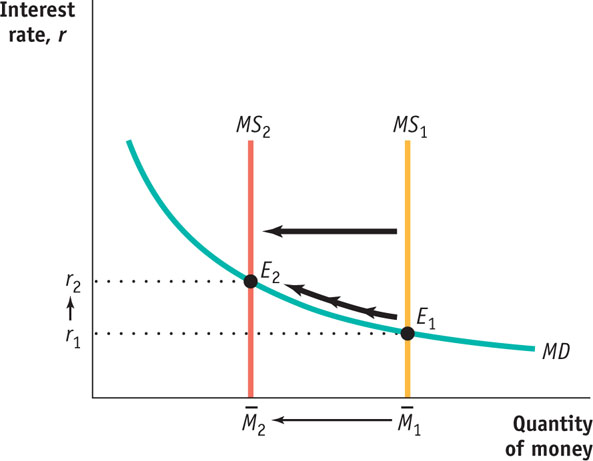

Draw the money demand curve, MD, and the money supply curve, MS, in order to show how the liquidity preference model predicts that a decrease in the money supply raises interest rates.

Read the section “Money and Interest Rates,” beginning on page 523. Pay close attention to Figure 17-4 on page 525.

A decrease in the money supply shifts the MS curve to the left, from  to

to  , as in the following diagram. The interest rate increases from r1 to r2 because of the downward sloping money demand curve.

, as in the following diagram. The interest rate increases from r1 to r2 because of the downward sloping money demand curve.

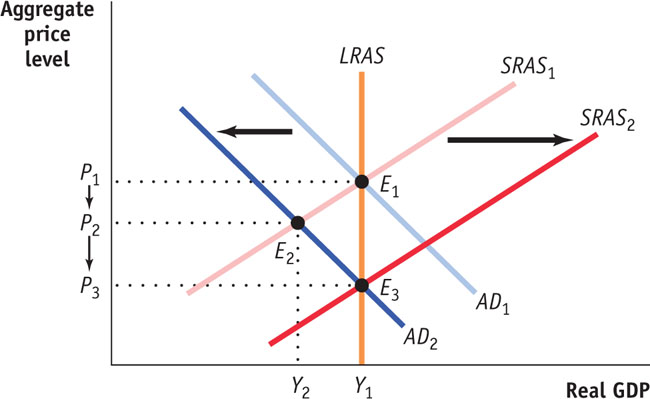

Draw the short-run and long-run effects of a decrease in the money supply on GDP and prices by drawing the LRAS curve, the AD curves, and the SRAS curves before and after a decrease in the money supply.

Read the section “Short-Run and Long-Run Effects of an Increase in the Money Supply,” beginning on page 534. Study Figure 17-11 on the same page, but note that a decrease in the money supply shifts the AD curve to the left, not to the right as in the figure.

Other things being equal, a decrease in the money supply increases the interest rate, which reduces investment spending and leads to a further fall in consumer spending. So, as shown in the following diagram, a decrease in the money supply decreases the quantity of goods and services demanded, shifting the AD curve leftward to AD2. The price level falls from P1 to P2, and real GDP falls from Y1 to Y2.

However, the aggregate output level Y2 is below potential output. As a result, nominal wages will fall over time, causing the SRAS curve to shift rightward. Prices fall further, to P3, but GDP returns to potential output at Y1. The economy ends up at point E3, a point of both short-run and long-run equilibrium.

Thus, in 1937, monetary policy simply made things worse for the economy by decreasing GDP in the short run, and putting further downward pressure on prices in the short and long run.